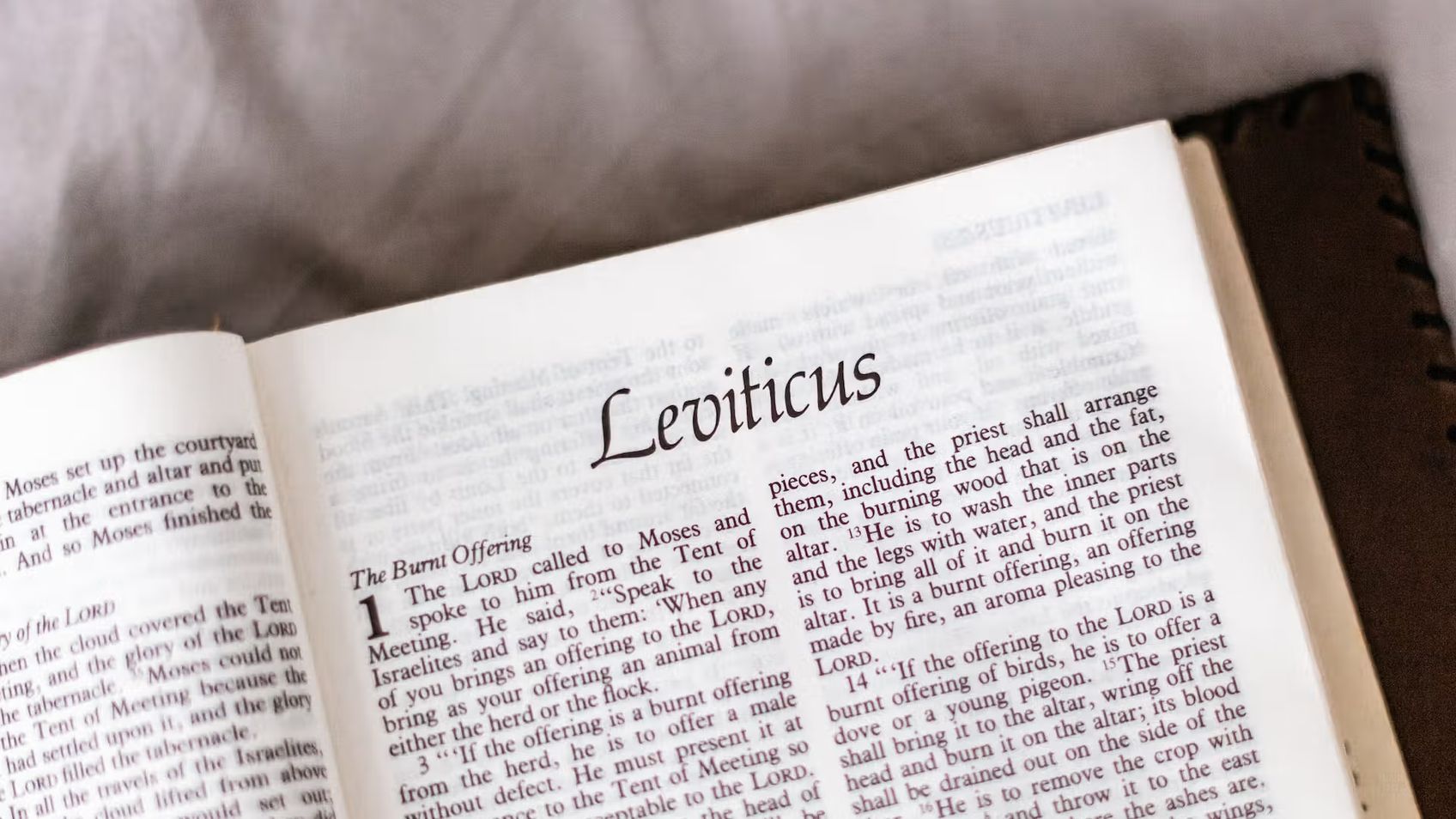

Leviticus Introduction

LeviticusSteve Gregg

Leviticus may seem tedious and irrelevant, but Steve Gregg highlights the importance of understanding God's character and the significance of the laws given in this book. While the book addresses the priesthood, it also addresses the people and their conduct. The concept of holiness and cleanliness is emphasized, with the word "clean" and its derivatives appearing 186 times in Leviticus. Although some of the laws described may not apply today, they can still teach us about the magnitude of the actions penalized and our need for grace and forgiveness.

More from Leviticus

2 of 12

Next in this series

Leviticus 1 - 7 (Part 1)

Leviticus

Steve Gregg delves into the spiritual significance and lessons we can learn from the first seven chapters of Leviticus. He explains the different type

3 of 12

Leviticus 1 - 7 (Part 2)

Leviticus

The acceptability of sacrifices according to the Jewish Law is determined by the character, intentions, and relationship with God of the person offeri

Series by Steve Gregg

Numbers

Steve Gregg's series on the book of Numbers delves into its themes of leadership, rituals, faith, and guidance, aiming to uncover timeless lessons and

Charisma and Character

In this 16-part series, Steve Gregg discusses various gifts of the Spirit, including prophecy, joy, peace, and humility, and emphasizes the importance

What You Absolutely Need To Know Before You Get Married

Steve Gregg's lecture series on marriage emphasizes the gravity of the covenant between two individuals and the importance of understanding God's defi

The Life and Teachings of Christ

This 180-part series by Steve Gregg delves into the life and teachings of Christ, exploring topics such as prayer, humility, resurrection appearances,

Gospel of Matthew

Spanning 72 hours of teaching, Steve Gregg's verse by verse teaching through the Gospel of Matthew provides a thorough examination of Jesus' life and

Some Assembly Required

Steve Gregg's focuses on the concept of the Church as a universal movement of believers, emphasizing the importance of community and loving one anothe

Hebrews

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the book of Hebrews, focusing on themes, warnings, the new covenant, judgment, faith, Jesus' authority, and

Ruth

Steve Gregg provides insightful analysis on the biblical book of Ruth, exploring its historical context, themes of loyalty and redemption, and the cul

Ezekiel

Discover the profound messages of the biblical book of Ezekiel as Steve Gregg provides insightful interpretations and analysis on its themes, propheti

2 Samuel

Steve Gregg provides a verse-by-verse analysis of the book of 2 Samuel, focusing on themes, characters, and events and their relevance to modern-day C

More on OpenTheo

How Do I Determine Which Topics at Work Are Worth Commenting On?

#STRask

January 5, 2026

Questions about how to determine which topics at work are worth commenting on, and a good way to respond when you’re in a group Bible study and hear e

How Can I Explain Modesty to My Daughter?

#STRask

November 27, 2025

Questions about how to explain modesty to a nine-year-old in a way that won’t cause shame about her body, and when and how to tell a child about a pre

Protestants and Catholics: What’s the Difference? With Chad Van Dixhoorn, Blair Smith, and Mark McDowell

Life and Books and Everything

November 26, 2025

How should Protestants think about the Catholic Mass? About the Eucharist? About the history and development of the papacy? In this panel discussion,

Is 1 Corinthians 12:3 a Black-and-White Tool for Discernment?

#STRask

October 27, 2025

Questions about whether the claim in 1 Corinthians that “no one can say ‘Jesus is Lord’ except in the Holy Spirit” is a black-and-white tool for disce

Christmas Cranks and Christmas Blessings with Justin Taylor and Collin Hansen

Life and Books and Everything

December 17, 2025

If you are looking for a podcast where three friends talk about whatever they want to talk about and ramble on about sports, books, and grievances, th

The Man on the Middle Cross with Alistair Begg

Life and Books and Everything

November 10, 2025

If you haven’t seen the viral clip, go see it right now. In this episode, Kevin talks to Alistair about the preaching clip he didn’t intend to give, h

Why Does the Bible Teach You How to Be a Proper Slave Owner?

#STRask

November 13, 2025

Question about why it seems like the Bible teaches you how to be a proper slave owner rather than than saying, “Stop it. Give them freedom.”

* It s

Did Jesus Prove He Wasn’t Sinless When He Overturned the Tables?

#STRask

December 29, 2025

Questions about whether Jesus proved he wasn’t sinless when he overturned the tables, whether Jesus’ response to the Pharisees in Mark 3:22–26 was a b

How Could the Similarities Between Krishna and Jesus Be a Coincidence?

#STRask

October 9, 2025

Questions about how the similarities between Krishna and Jesus could be a coincidence and whether there’s any proof to substantiate the idea that Jesu

“Christians Care More About Ideology than People”

#STRask

October 13, 2025

Questions about how to respond to the critique that Christians care more about ideology than people, and whether we have freedom in America because Ch

Can Two Logical People Come to Conflicting Conclusions Without Committing a Fallacy?

#STRask

January 8, 2026

Questions about whether two logical people can come to conflicting conclusions on a topic without committing a fallacy, how Greg, as a public figure,

What Is Wrong with Wokeness? With Neil Shenvi

Life and Books and Everything

January 19, 2026

In this timely interview, Kevin talks to Neil Shenvi about his new book (co-authored with Pat Sawyer), entitled “Post Woke: Asserting a Biblical Visio

Can You Provide Verifiable, Non-Religious Evidence That a Supernatural Jesus Existed?

#STRask

November 10, 2025

Question about providing verifiable, non-religious evidence that a supernatural Jesus existed.

* I am an atheist and militantly anti-god-belief. Ho

Prove to Me That Jesus Is Not a Created Being

#STRask

January 26, 2026

Questions about why we should think Jesus is not a created being, and what it means to say God became fully human if part of being human means not bei

Why Would Any Rational Person Have to Use Any Religious Book?

#STRask

December 8, 2025

Questions about why any rational person would have to use any religious book, whether apologetics would be redundant if there were actually a good, un