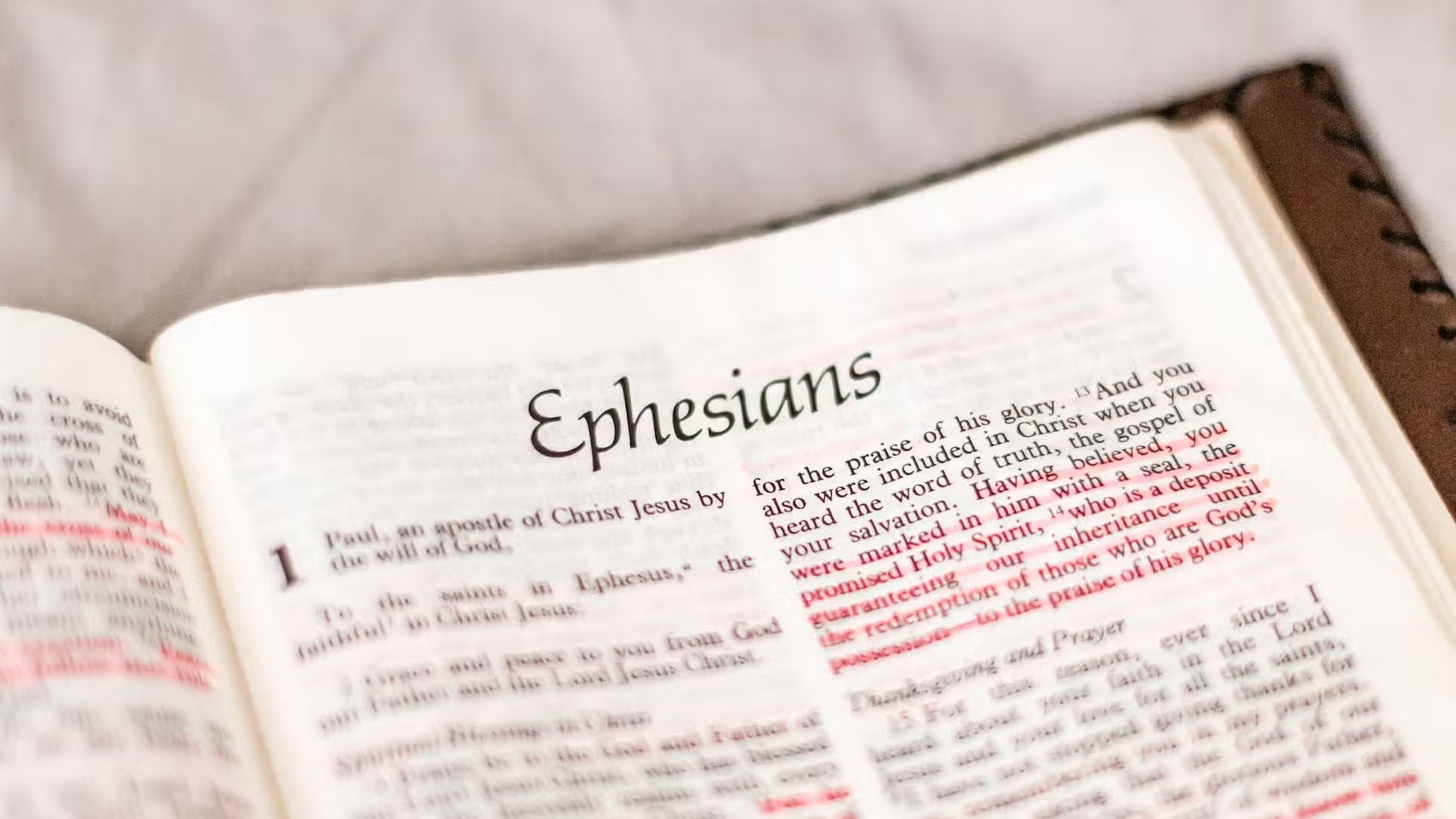

Ephesians Introduction, 1:1 - 1:6

EphesiansSteve Gregg

In this introduction to the book of Ephesians, Steve Gregg discusses the origins of the letter and how it relates to other Pauline epistles. He explains that Ephesians is a generic letter to the universal Church, and not specifically to the Church in Ephesus. Gregg also delves into the concept of predestination and explains that being predestined does not necessarily equate to the Calvinist doctrine. Overall, Gregg offers an insightful overview of the book of Ephesians, providing context and shedding light on key themes.

More from Ephesians

2 of 10

Next in this series

Ephesians 1:6 - 1:23

Ephesians

In this talk, Steve Gregg focuses on Ephesians 1:6-23 and discusses the relationship between the church, God the Father, and Christ. He emphasizes the

3 of 10

Ephesians 2

Ephesians

In this teaching, Steve Gregg delves into Ephesians 2 and discusses the concept of salvation by grace through faith. He notes that salvation is a gift

Series by Steve Gregg

Joel

Steve Gregg provides a thought-provoking analysis of the book of Joel, exploring themes of judgment, restoration, and the role of the Holy Spirit.

1 Corinthians

Steve Gregg provides a verse-by-verse exposition of 1 Corinthians, delving into themes such as love, spiritual gifts, holiness, and discipline within

Foundations of the Christian Faith

This series by Steve Gregg delves into the foundational beliefs of Christianity, including topics such as baptism, faith, repentance, resurrection, an

Leviticus

In this 12-part series, Steve Gregg provides insightful analysis of the book of Leviticus, exploring its various laws and regulations and offering spi

What You Absolutely Need To Know Before You Get Married

Steve Gregg's lecture series on marriage emphasizes the gravity of the covenant between two individuals and the importance of understanding God's defi

Cultivating Christian Character

Steve Gregg's lecture series focuses on cultivating holiness and Christian character, emphasizing the need to have God's character and to walk in the

How Can I Know That I Am Really Saved?

In this four-part series, Steve Gregg explores the concept of salvation using 1 John as a template and emphasizes the importance of love, faith, godli

1 Kings

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the book of 1 Kings, providing insightful commentary on topics such as discernment, building projects, the

Gospel of John

In this 38-part series, Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the Gospel of John, providing insightful analysis and exploring important themes su

Obadiah

Steve Gregg provides a thorough examination of the book of Obadiah, exploring the conflict between Israel and Edom and how it relates to divine judgem

More on OpenTheo

Does God Really Need a “Pound of Flesh” to Forgive Sins?

#STRask

January 12, 2026

Questions about how to answer the challenge that God doesn’t need a “pound of flesh” to forgive sins but can simply forgive, and whether the claim in

How Can We Know Who Is Teaching the Same Gospel Paul Taught?

#STRask

February 16, 2026

Questions about how we can know who is teaching the same gospel Paul taught, and whether or not Jeremiah 1:5 supports the idea that we pre-existed in

How Do You Justify Calling Jesus the Messiah?

#STRask

December 18, 2025

Questions about how one can justify calling Jesus the Messiah when he didn’t fulfill the Hebrew messianic prophecies, and whether the reason for the v

How Can I Explain Modesty to My Daughter?

#STRask

November 27, 2025

Questions about how to explain modesty to a nine-year-old in a way that won’t cause shame about her body, and when and how to tell a child about a pre

Why Does the Bible Teach You How to Be a Proper Slave Owner?

#STRask

November 13, 2025

Question about why it seems like the Bible teaches you how to be a proper slave owner rather than than saying, “Stop it. Give them freedom.”

* It s

Life and Ministry in Charlotte and in the SBC with Clint Pressley

Life and Books and Everything

December 15, 2025

In a rare cultural anomaly that may never be repeated in our lifetimes, the current SBC President and current PCA Moderator live in the same neighborh

When I Can’t Stop Thinking About Something, Is That God Speaking?

#STRask

December 1, 2025

Questions about whether having a recurring thought is an indication God is speaking to you, what to say to someone who says they sinned because “God t

Could the Writers of Scripture Have Been Influenced by Their Fallen Nature?

#STRask

October 23, 2025

Questions about whether or not it’s reasonable to worry that some of our current doctrines were influenced by the fallen nature of the apostles, and h

Protestants and Catholics: What’s the Difference? With Chad Van Dixhoorn, Blair Smith, and Mark McDowell

Life and Books and Everything

November 26, 2025

How should Protestants think about the Catholic Mass? About the Eucharist? About the history and development of the papacy? In this panel discussion,

Why Is It Necessary to Believe Jesus Is God?

#STRask

February 19, 2026

Questions about why it’s necessary to believe Jesus is God, whether belief in the Trinity is required for salvation, and why one has to believe in the

Does Open-Mindedness Require Studying Other Religions Before Becoming a Christian?

#STRask

February 9, 2026

Questions about the claim that if Christians really want to be open-minded, they need to read and study other religions before committing to Christian

The Making of the American Mind with Matthew Spalding

Life and Books and Everything

February 2, 2026

The United States is unique in how much attention it pays to its founding, its founders, and its founding documents. Arguably, the most famous and mos

Are You Accursed If You Tithe?

#STRask

December 15, 2025

Questions about whether anyone who tithes is not a Christian and is accursed since Paul says that if you obey one part of the Mosaic Law you’re obliga

Is It Possible There’s a Being That’s Greater Than God?

#STRask

February 5, 2026

Questions about whether it’s possible there’s a being that’s greater than God and that’s outside of God’s comprehension and omniscience, and how to ex

Can You Provide Verifiable, Non-Religious Evidence That a Supernatural Jesus Existed?

#STRask

November 10, 2025

Question about providing verifiable, non-religious evidence that a supernatural Jesus existed.

* I am an atheist and militantly anti-god-belief. Ho