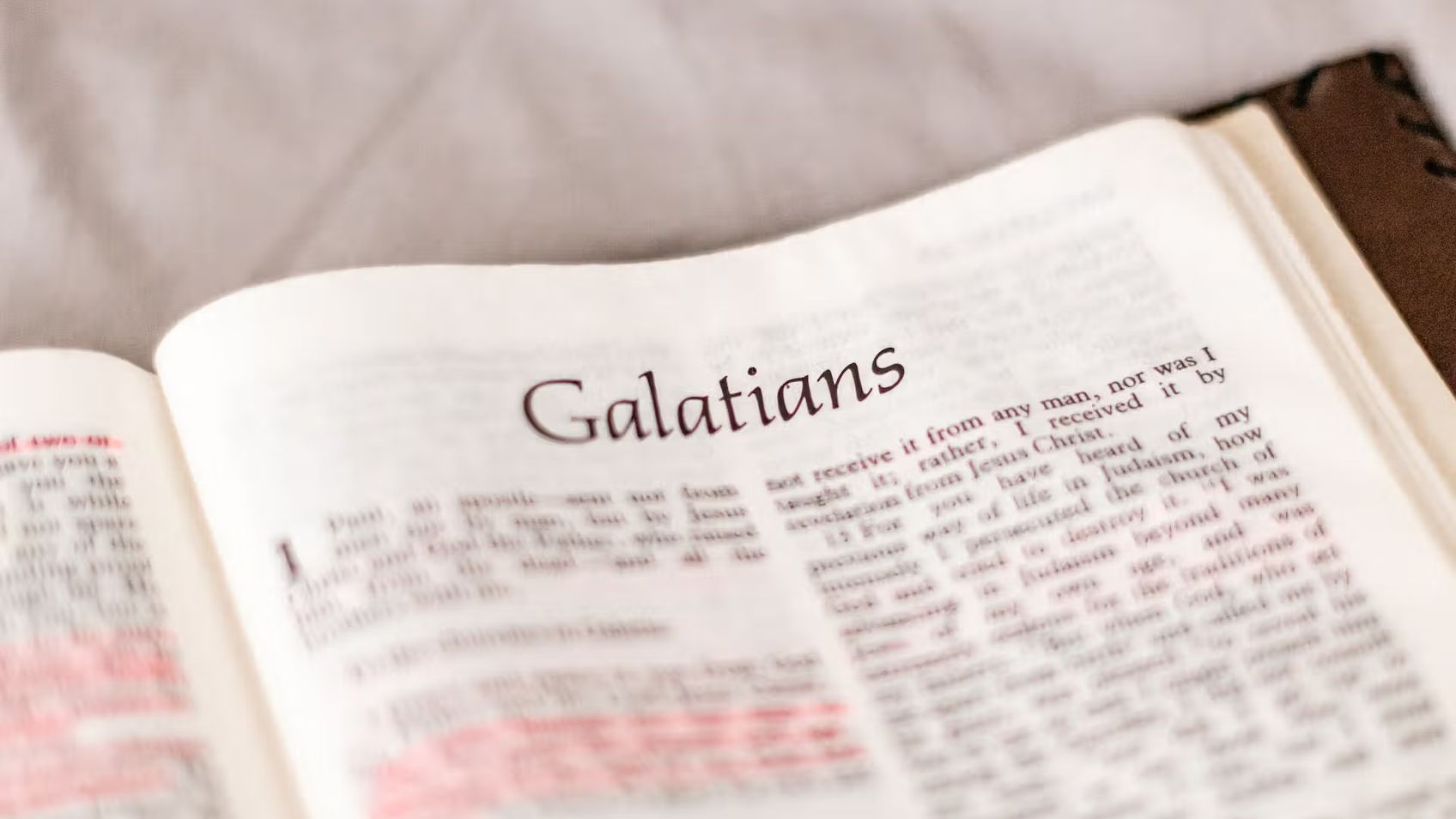

Galatians 3:19 - 4:7

GalatiansSteve Gregg

Steve Gregg discusses Galatians 3:19 - 4:7 and the concept of faith in the Christian faith. Gregg makes the point that faith, not obedience to the law, is what saves people. He also emphasizes that the law was added because of transgressions until the Messiah, or Christ, came. Abraham, despite his imperfections, was justified by faith, and the covenant God made with him was fulfilled in Christ, not in the nation of Israel. Gregg stresses that Christians are children of God by faith in Christ and that God sent his spirit to confirm their relationship with him.

More from Galatians

5 of 6

Next in this series

Galatians 4:8 - 5:12

Galatians

In this discussion, Steve Gregg provides a thorough examination of Galatians 4:8 - 5:12. He breaks down the different concepts mentioned in the text,

6 of 6

Galatians 5:13 - 6:18

Galatians

In this session, Steve Gregg analyzes Galatians 5:13 to 6:18, focusing on the theme of love as the fruit of the Spirit. He emphasizes the importance o

3 of 6

Galatians 3:1 - 3:18

Galatians

In this commentary on Galatians 3:1-18, Steve Gregg discusses the idea that true obedience to God comes from a heart filled with love and gratitude, r

Series by Steve Gregg

Ten Commandments

Steve Gregg delivers a thought-provoking and insightful lecture series on the relevance and importance of the Ten Commandments in modern times, delvin

Titus

In this four-part series from Steve Gregg, listeners are taken on an insightful journey through the book of Titus, exploring issues such as good works

The Life and Teachings of Christ

This 180-part series by Steve Gregg delves into the life and teachings of Christ, exploring topics such as prayer, humility, resurrection appearances,

Ezekiel

Discover the profound messages of the biblical book of Ezekiel as Steve Gregg provides insightful interpretations and analysis on its themes, propheti

Joshua

Steve Gregg's 13-part series on the book of Joshua provides insightful analysis and application of key themes including spiritual warfare, obedience t

Jude

Steve Gregg provides a comprehensive analysis of the biblical book of Jude, exploring its themes of faith, perseverance, and the use of apocryphal lit

Genuinely Following Jesus

Steve Gregg's lecture series on discipleship emphasizes the importance of following Jesus and becoming more like Him in character and values. He highl

Galatians

In this six-part series, Steve Gregg provides verse-by-verse commentary on the book of Galatians, discussing topics such as true obedience, faith vers

Individual Topics

This is a series of over 100 lectures by Steve Gregg on various topics, including idolatry, friendships, truth, persecution, astrology, Bible study,

Evangelism

Evangelism by Steve Gregg is a 6-part series that delves into the essence of evangelism and its role in discipleship, exploring the biblical foundatio

More on OpenTheo

Why Is It Necessary to Believe Jesus Is God?

#STRask

February 19, 2026

Questions about why it’s necessary to believe Jesus is God, whether belief in the Trinity is required for salvation, and why one has to believe in the

Prove to Me That Jesus Is Not a Created Being

#STRask

January 26, 2026

Questions about why we should think Jesus is not a created being, and what it means to say God became fully human if part of being human means not bei

How Can I Explain Modesty to My Daughter?

#STRask

November 27, 2025

Questions about how to explain modesty to a nine-year-old in a way that won’t cause shame about her body, and when and how to tell a child about a pre

Why Would Any Rational Person Have to Use Any Religious Book?

#STRask

December 8, 2025

Questions about why any rational person would have to use any religious book, whether apologetics would be redundant if there were actually a good, un

Life and Ministry in Charlotte and in the SBC with Clint Pressley

Life and Books and Everything

December 15, 2025

In a rare cultural anomaly that may never be repeated in our lifetimes, the current SBC President and current PCA Moderator live in the same neighborh

What Are Some Good Ways to Start a Conversation About God with Family Members?

#STRask

October 30, 2025

Questions about how to start a conversation about God with non-Christian family members, how to keep from becoming emotional when discussing faith iss

What Is Wrong with Wokeness? With Neil Shenvi

Life and Books and Everything

January 19, 2026

In this timely interview, Kevin talks to Neil Shenvi about his new book (co-authored with Pat Sawyer), entitled “Post Woke: Asserting a Biblical Visio

Did God Create Us So He Wouldn’t Be Alone?

#STRask

November 3, 2025

Questions about whether God created us so he wouldn’t be alone, what he had before us, and a comparison between the Muslim view of God and the Christi

Why Does the Bible Teach You How to Be a Proper Slave Owner?

#STRask

November 13, 2025

Question about why it seems like the Bible teaches you how to be a proper slave owner rather than than saying, “Stop it. Give them freedom.”

* It s

Is It a Sin to Feel Let Down by God?

#STRask

November 6, 2025

Questions about whether it’s a sin to feel let down by God and whether it would be easier to have a personal relationship with a rock than with a God

Conservatism and Religious Freedom with John Wilsey

Life and Books and Everything

October 27, 2025

What is conservatism? And why does it go hand in hand with religious freedom? How should we think about the American experiment of ordered liberty? Ha

Did Jesus Prove He Wasn’t Sinless When He Overturned the Tables?

#STRask

December 29, 2025

Questions about whether Jesus proved he wasn’t sinless when he overturned the tables, whether Jesus’ response to the Pharisees in Mark 3:22–26 was a b

Can You Provide Verifiable, Non-Religious Evidence That a Supernatural Jesus Existed?

#STRask

November 10, 2025

Question about providing verifiable, non-religious evidence that a supernatural Jesus existed.

* I am an atheist and militantly anti-god-belief. Ho

An Invitation to the 2026 Coram Deo Pastors Conference

Life and Books and Everything

February 18, 2026

"I love being a pastor, and I love pastors, which is why I hope you will consider joining us at the Coram Deo Pastors Conference in 2026." —Kevin DeYo

How Can We Know Who Is Teaching the Same Gospel Paul Taught?

#STRask

February 16, 2026

Questions about how we can know who is teaching the same gospel Paul taught, and whether or not Jeremiah 1:5 supports the idea that we pre-existed in