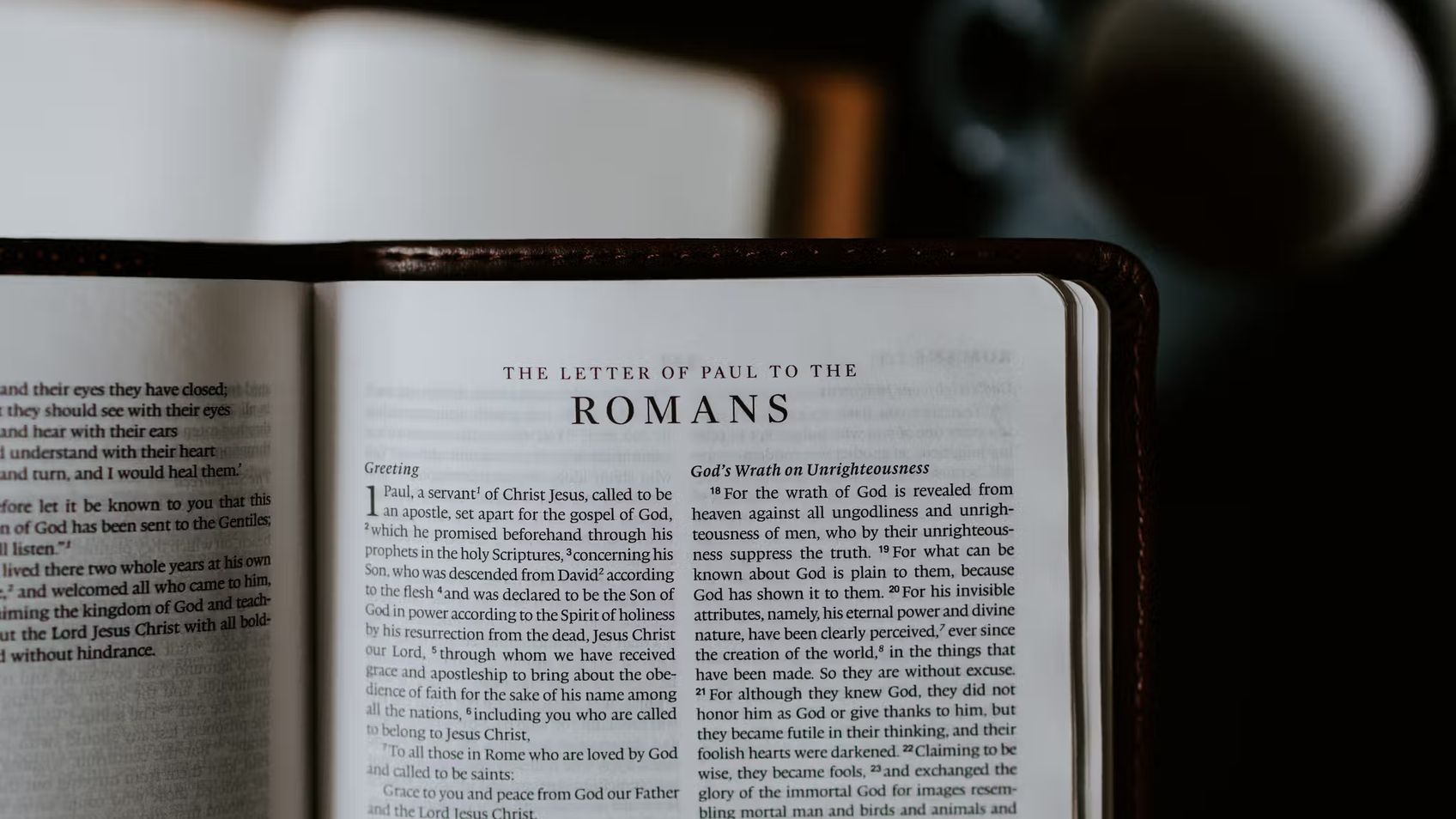

Romans 5:12 - 21 (Part 2)

RomansSteve Gregg

The debate on the concept of inherited sin among Christians is discussed in this passage from Romans 5:12-21. While some believe in a sinful nature passed down from Adam, others follow the Augustinian view that all humans are born guilty for Adam's sin. The passage emphasizes differences between Adam's selfish motive for sinning and Christ's gracious act of salvation, and through personification, Paul presents a drama where grace ultimately overcomes and abounds. The need to live in righteousness and not as slaves to sin is also emphasized, and the passage concludes with the idea that through Christ's sacrifice, we are made righteous and victorious over sin and death.

More from Romans

15 of 29

Next in this series

Romans 6:1 - 6:14

Romans

In this discussion, the appropriate ramifications of salvation in life with regards to sinning is addressed. Baptism is important in the early church

16 of 29

Romans 6:15 - 6:23

Romans

The passage from Romans 6:15-6:23 emphasizes that Christians should not continue to live in sin despite being saved by grace rather than the law. Paul

13 of 29

Romans 5:12 - 21 (Part 1)

Romans

The passage of Romans 5:12-21 reflects on the impact of Adam and Christ on humanity. While theologians have debated the theological nuances of this pa

Series by Steve Gregg

Daniel

Steve Gregg discusses various parts of the book of Daniel, exploring themes of prophecy, historical accuracy, and the significance of certain events.

Nehemiah

A comprehensive analysis by Steve Gregg on the book of Nehemiah, exploring the story of an ordinary man's determination and resilience in rebuilding t

How Can I Know That I Am Really Saved?

In this four-part series, Steve Gregg explores the concept of salvation using 1 John as a template and emphasizes the importance of love, faith, godli

Torah Observance

In this 4-part series titled "Torah Observance," Steve Gregg explores the significance and spiritual dimensions of adhering to Torah teachings within

Genesis

Steve Gregg provides a detailed analysis of the book of Genesis in this 40-part series, exploring concepts of Christian discipleship, faith, obedience

Judges

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the Book of Judges in this 16-part series, exploring its historical and cultural context and highlighting t

Zechariah

Steve Gregg provides a comprehensive guide to the book of Zechariah, exploring its historical context, prophecies, and symbolism through ten lectures.

Joel

Steve Gregg provides a thought-provoking analysis of the book of Joel, exploring themes of judgment, restoration, and the role of the Holy Spirit.

1 Samuel

In this 15-part series, Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the biblical book of 1 Samuel, examining the story of David's journey to becoming k

Original Sin & Depravity

In this two-part series by Steve Gregg, he explores the theological concepts of Original Sin and Human Depravity, delving into different perspectives

More on OpenTheo

Is It a Sin to Feel Let Down by God?

#STRask

November 6, 2025

Questions about whether it’s a sin to feel let down by God and whether it would be easier to have a personal relationship with a rock than with a God

Why Should We Pray If God Already Knows What’s Going to Happen?

#STRask

January 29, 2026

Questions about why we should pray if God already knows what’s going to happen, how the effectiveness of prayer is measured, and whether or not things

Life and Ministry in Charlotte and in the SBC with Clint Pressley

Life and Books and Everything

December 15, 2025

In a rare cultural anomaly that may never be repeated in our lifetimes, the current SBC President and current PCA Moderator live in the same neighborh

Can You Provide Verifiable, Non-Religious Evidence That a Supernatural Jesus Existed?

#STRask

November 10, 2025

Question about providing verifiable, non-religious evidence that a supernatural Jesus existed.

* I am an atheist and militantly anti-god-belief. Ho

An Invitation to the 2026 Coram Deo Pastors Conference

Life and Books and Everything

February 18, 2026

"I love being a pastor, and I love pastors, which is why I hope you will consider joining us at the Coram Deo Pastors Conference in 2026." —Kevin DeYo

What Is Wrong with Wokeness? With Neil Shenvi

Life and Books and Everything

January 19, 2026

In this timely interview, Kevin talks to Neil Shenvi about his new book (co-authored with Pat Sawyer), entitled “Post Woke: Asserting a Biblical Visio

Sense, Sensibility, and Adam Smith with Jan Van Vliet

Life and Books and Everything

February 16, 2026

This year is a special anniversary for the United States as Americans celebrate 250 years of independence. But 1776 was an important year in more ways

Shouldn’t I Be Praying for My Soul Rather Than for Material Things?

#STRask

February 2, 2026

Questions about whether we should be praying for our souls rather than for material things, why we need to pray about decisions, whether the devil can

The Man on the Middle Cross with Alistair Begg

Life and Books and Everything

November 10, 2025

If you haven’t seen the viral clip, go see it right now. In this episode, Kevin talks to Alistair about the preaching clip he didn’t intend to give, h

How Do I Determine Which Topics at Work Are Worth Commenting On?

#STRask

January 5, 2026

Questions about how to determine which topics at work are worth commenting on, and a good way to respond when you’re in a group Bible study and hear e

Does Open-Mindedness Require Studying Other Religions Before Becoming a Christian?

#STRask

February 9, 2026

Questions about the claim that if Christians really want to be open-minded, they need to read and study other religions before committing to Christian

The Making of the American Mind with Matthew Spalding

Life and Books and Everything

February 2, 2026

The United States is unique in how much attention it pays to its founding, its founders, and its founding documents. Arguably, the most famous and mos

Did God Create Us So He Wouldn’t Be Alone?

#STRask

November 3, 2025

Questions about whether God created us so he wouldn’t be alone, what he had before us, and a comparison between the Muslim view of God and the Christi

What Do You Think About Churches Advertising on Social Media?

#STRask

January 19, 2026

Questions about whether there’s an issue with churches advertising on social media, whether it’s weird if we pray along with a YouTuber, and whether C

What Is the Role of the Holy Spirit in Our Lives if He Doesn’t Give Us Instructions?

#STRask

February 23, 2026

Questions about the role of the Holy Spirit in our lives, advice for someone who believes in God intellectually but struggles to understand how to hav