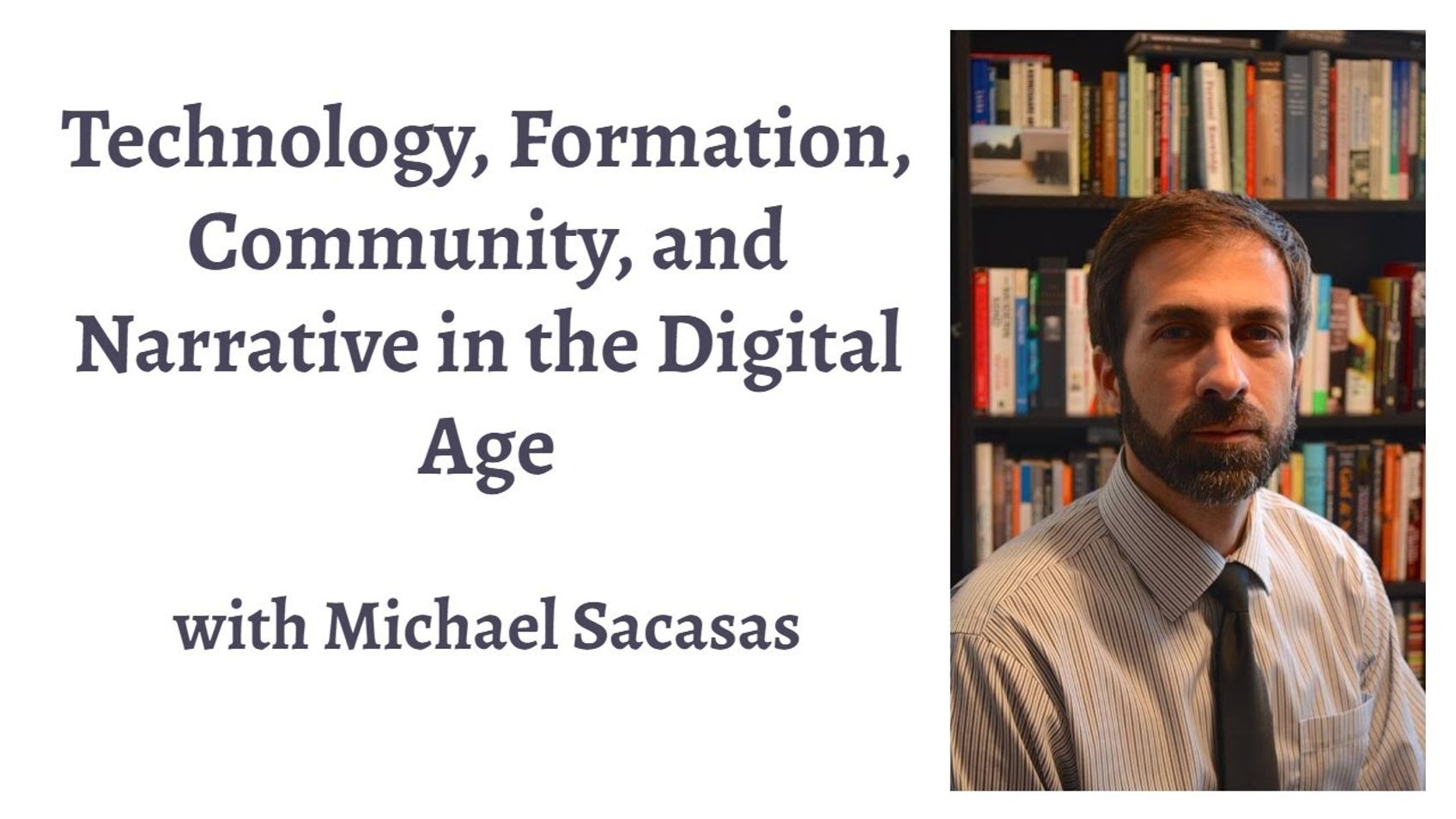

Technology, Formation, Community, and Narrative in the Digital Age (Michael Sacasas)

Alastair RobertsTechnology, Formation, Community, and Narrative in the Digital Age (Michael Sacasas)

Michael Sacasas, one of the most thoughtful contemporary commentators on technology and media, joins me for a wide-ranging conversation.

Read more of his work here:

'The Analog City and the Digital City': https://www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/the-analog-city-and-the-digital-city

Narrative Collapse: https://theconvivialsociety.substack.com/p/narrative-collapse

Sign up for The Convivial Society newsletter: https://theconvivialsociety.substack.com/

The Frailest Thing: https://thefrailestthing.com/the-frailest-thing/

Frailest Thing compilation book: https://gumroad.com/l/CWRfq

Recommended Books:

Neil Postman, 'Technopoly': https://amzn.to/3gt3u9J

Marshall McLuhan, 'Understanding Media': https://amzn.to/2NP2GQu

Walter Ong, 'Orality and Literacy': https://amzn.to/2NVxkaK

Albert Borgmann, 'Power Failure': https://amzn.to/38somuY

Ivan Illich, 'Tools for Conviviality': https://amzn.to/2Asqnel

Jacques Ellul, 'The Technological Society': https://amzn.to/31IYSZi

If you have enjoyed my output, please tell your friends. If you are interested in supporting my videos and podcasts and my research more generally, please consider supporting my work on Patreon (https://www.patreon.com/zugzwanged), using my PayPal account (https://bit.ly/2RLaUcB), or by buying books for my research on Amazon (https://www.amazon.co.uk/hz/wishlist/ls/36WVSWCK4X33O?ref_=wl_share).

The audio of all of my videos is available on my Soundcloud account: https://soundcloud.com/alastairadversaria. You can also listen to the audio of these episodes on iTunes: https://itunes.apple.com/gb/podcast/alastairs-adversaria/id1416351035?mt=2.

More From Alastair Roberts

More on OpenTheo