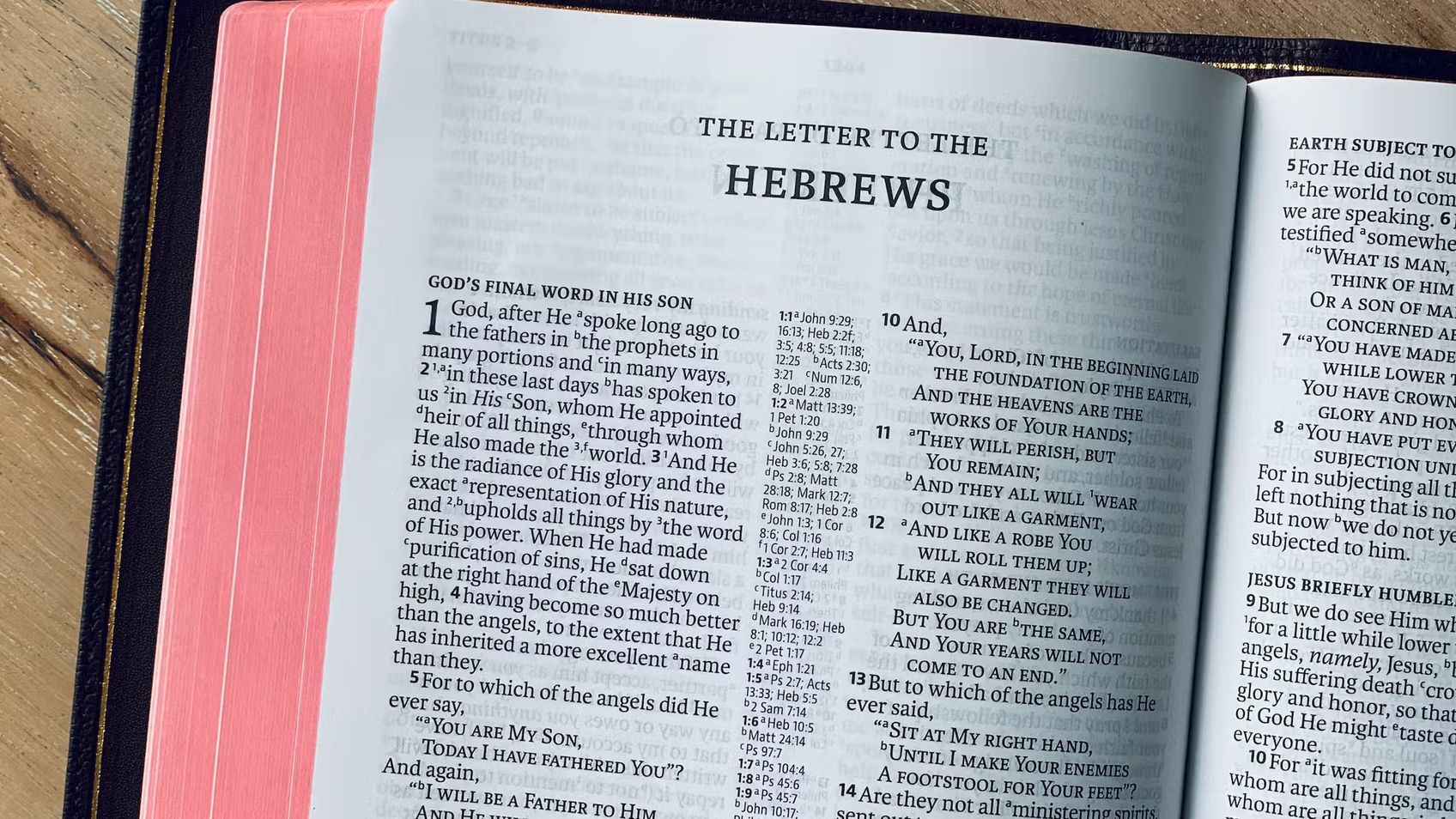

Hebrews 3

HebrewsSteve Gregg

In this discussion, Steve Gregg delves into the conditional nature of holding fast to one's Christian faith until the end. He highlights the importance of obedience and faith as demonstrated by Jesus and warns against becoming obstinate and straying from the path of faith. Drawing from biblical text, he emphasizes that it is not enough to simply believe in God, but faith must be demonstrated through works. Ultimately, he stresses the need to follow Jesus and hold firm in one's faith until the end.

More from Hebrews

6 of 15

Next in this series

Hebrews 4

Hebrews

Steve Gregg discusses Hebrews chapter 4 where he examines the idea of rest as entering the promised land. He notes that the writer of Hebrews sees a s

7 of 15

Hebrews 5

Hebrews

In this presentation, Steve Gregg discusses the book of Hebrews and focuses specifically on chapter 5. He notes that the author of Hebrews later hints

4 of 15

Hebrews 2

Hebrews

In this lecture, Steve Gregg explores the second chapter of Hebrews, which focuses on Jesus as a superior revelation of God. Gregg emphasizes the impo

Series by Steve Gregg

Song of Songs

Delve into the allegorical meanings of the biblical Song of Songs and discover the symbolism, themes, and deeper significance with Steve Gregg's insig

What You Absolutely Need To Know Before You Get Married

Steve Gregg's lecture series on marriage emphasizes the gravity of the covenant between two individuals and the importance of understanding God's defi

Foundations of the Christian Faith

This series by Steve Gregg delves into the foundational beliefs of Christianity, including topics such as baptism, faith, repentance, resurrection, an

Toward a Radically Christian Counterculture

Steve Gregg presents a vision for building a distinctive and holy Christian culture that stands in opposition to the values of the surrounding secular

Message For The Young

In this 6-part series, Steve Gregg emphasizes the importance of pursuing godliness and avoiding sinful behavior as a Christian, encouraging listeners

Micah

Steve Gregg provides a verse-by-verse analysis and teaching on the book of Micah, exploring the prophet's prophecies of God's judgment, the birthplace

The Life and Teachings of Christ

This 180-part series by Steve Gregg delves into the life and teachings of Christ, exploring topics such as prayer, humility, resurrection appearances,

Survey of the Life of Christ

Steve Gregg's 9-part series explores various aspects of Jesus' life and teachings, including his genealogy, ministry, opposition, popularity, pre-exis

Word of Faith

"Word of Faith" by Steve Gregg is a four-part series that provides a detailed analysis and thought-provoking critique of the Word Faith movement's tea

Knowing God

Knowing God by Steve Gregg is a 16-part series that delves into the dynamics of relationships with God, exploring the importance of walking with Him,

More on OpenTheo

The Making of the American Mind with Matthew Spalding

Life and Books and Everything

February 2, 2026

The United States is unique in how much attention it pays to its founding, its founders, and its founding documents. Arguably, the most famous and mos

Life and Ministry in Charlotte and in the SBC with Clint Pressley

Life and Books and Everything

December 15, 2025

In a rare cultural anomaly that may never be repeated in our lifetimes, the current SBC President and current PCA Moderator live in the same neighborh

Is Greg Placing His Faith in the Wrong Thing?

#STRask

February 12, 2026

Questions about Greg placing his faith in his personal assessment of which truth claims best match reality rather than in the revelation of God in Jes

Can You Provide Verifiable, Non-Religious Evidence That a Supernatural Jesus Existed?

#STRask

November 10, 2025

Question about providing verifiable, non-religious evidence that a supernatural Jesus existed.

* I am an atheist and militantly anti-god-belief. Ho

Why Would Any Rational Person Have to Use Any Religious Book?

#STRask

December 8, 2025

Questions about why any rational person would have to use any religious book, whether apologetics would be redundant if there were actually a good, un

Kingdom Priorities: Following the Teachings of Jesus

Knight & Rose Show

February 14, 2026

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose discuss Jesus' teachings from the Gospels, emphasizing truth, evidence, self-denial, and forgiveness. They explore pass

Shouldn’t I Be Praying for My Soul Rather Than for Material Things?

#STRask

February 2, 2026

Questions about whether we should be praying for our souls rather than for material things, why we need to pray about decisions, whether the devil can

Keri Ingraham: School Choice and Education Reform

Knight & Rose Show

January 24, 2026

Wintery Knight and guest host Bonnie welcome Dr. Keri Ingraham to discuss school choice and education reform. They discuss the public school monopoly'

Does Open-Mindedness Require Studying Other Religions Before Becoming a Christian?

#STRask

February 9, 2026

Questions about the claim that if Christians really want to be open-minded, they need to read and study other religions before committing to Christian

An Invitation to the 2026 Coram Deo Pastors Conference

Life and Books and Everything

February 18, 2026

"I love being a pastor, and I love pastors, which is why I hope you will consider joining us at the Coram Deo Pastors Conference in 2026." —Kevin DeYo

Are You Accursed If You Tithe?

#STRask

December 15, 2025

Questions about whether anyone who tithes is not a Christian and is accursed since Paul says that if you obey one part of the Mosaic Law you’re obliga

Did Jesus Prove He Wasn’t Sinless When He Overturned the Tables?

#STRask

December 29, 2025

Questions about whether Jesus proved he wasn’t sinless when he overturned the tables, whether Jesus’ response to the Pharisees in Mark 3:22–26 was a b

What About Those Who Never Heard the Name of Jesus?

#STRask

December 22, 2025

Questions about what will happen to those who never heard of Jesus or were brought up in a different faith, whether there’s biblical warrant to think

How Do You Justify Calling Jesus the Messiah?

#STRask

December 18, 2025

Questions about how one can justify calling Jesus the Messiah when he didn’t fulfill the Hebrew messianic prophecies, and whether the reason for the v

What Is the Role of the Holy Spirit in Our Lives if He Doesn’t Give Us Instructions?

#STRask

February 23, 2026

Questions about the role of the Holy Spirit in our lives, advice for someone who believes in God intellectually but struggles to understand how to hav