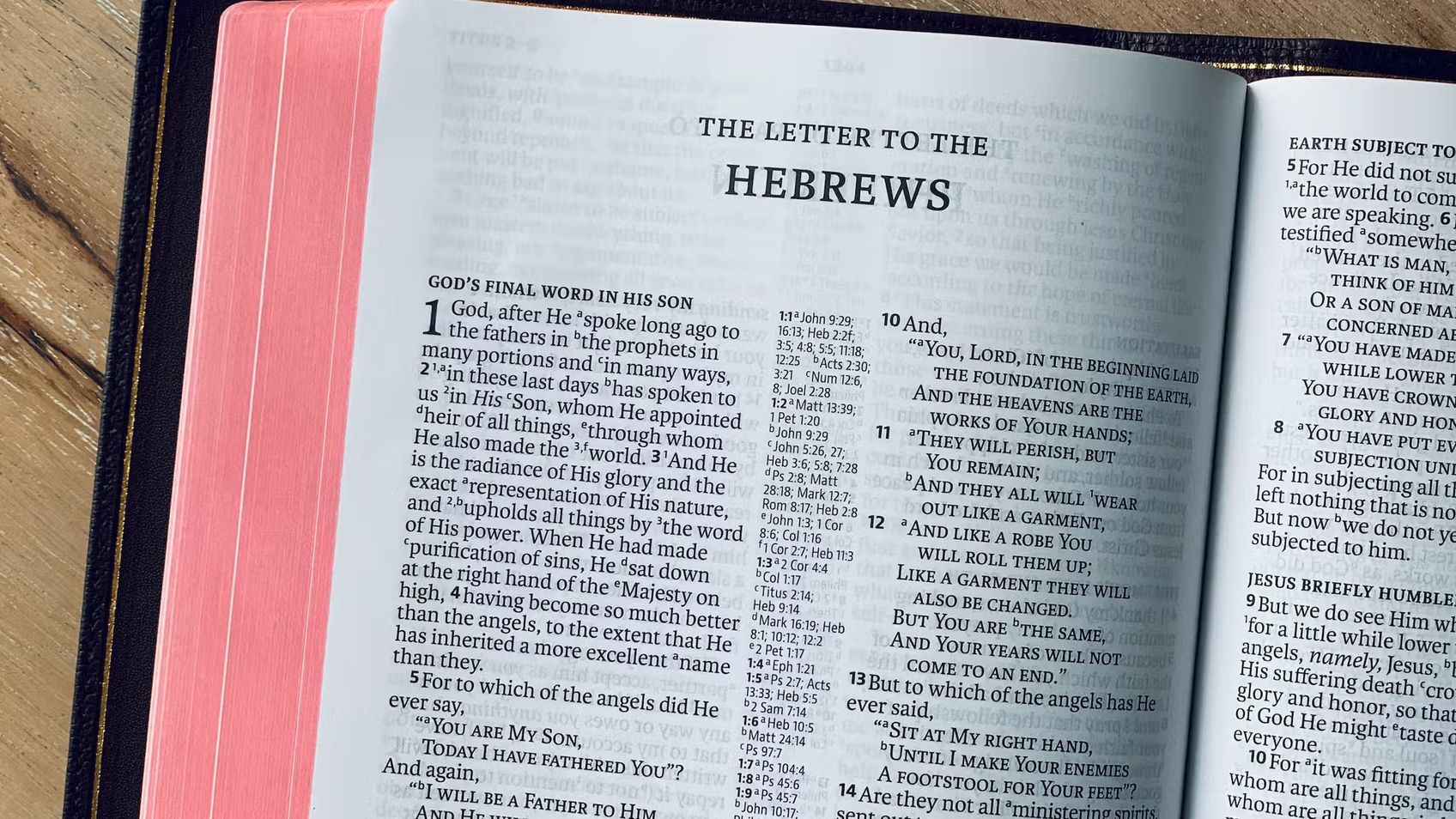

Hebrews 7

HebrewsSteve Gregg

In this teaching, Steve Gregg delves into Hebrews 7, where the author argues that the priesthood of Melchizedek differs from the Aaronic priesthood. Melchizedek's priesthood is based on eternal life and not hereditary succession. While commentators have differing views on who Melchizedek was, the author of Hebrews points to him as a type of Christ, with an unchangeable and non-transferable priesthood. The author's main goal is to sanctify believers and grow them in Christ's image.

More from Hebrews

10 of 15

Next in this series

Hebrews 8

Hebrews

In this talk, Steve Gregg explores the concept of the new covenant in Hebrews chapter eight. He contrasts the old covenant, which was written on stone

11 of 15

Hebrews 9

Hebrews

Steve Gregg discusses Hebrews chapter 9 and its references to Jewish customs and rituals, specifically the annual sacrifice for unintentional sins. Th

8 of 15

Hebrews 6

Hebrews

Steve Gregg discusses the warning section in Hebrews 6, which follows on from chapter 5's warning not to become stagnant in one's faith. Gregg suggest

Series by Steve Gregg

Philippians

In this 2-part series, Steve Gregg explores the book of Philippians, encouraging listeners to find true righteousness in Christ rather than relying on

2 Kings

In this 12-part series, Steve Gregg provides a thorough verse-by-verse analysis of the biblical book 2 Kings, exploring themes of repentance, reform,

Judges

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the Book of Judges in this 16-part series, exploring its historical and cultural context and highlighting t

Malachi

Steve Gregg's in-depth exploration of the book of Malachi provides insight into why the Israelites were not prospering, discusses God's election, and

Kingdom of God

An 8-part series by Steve Gregg that explores the concept of the Kingdom of God and its various aspects, including grace, priesthood, present and futu

Introduction to the Life of Christ

Introduction to the Life of Christ by Steve Gregg is a four-part series that explores the historical background of the New Testament, sheds light on t

Nehemiah

A comprehensive analysis by Steve Gregg on the book of Nehemiah, exploring the story of an ordinary man's determination and resilience in rebuilding t

1 Kings

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the book of 1 Kings, providing insightful commentary on topics such as discernment, building projects, the

1 Thessalonians

In this three-part series from Steve Gregg, he provides an in-depth analysis of 1 Thessalonians, touching on topics such as sexual purity, eschatology

Three Views of Hell

Steve Gregg discusses the three different views held by Christians about Hell: the traditional view, universalism, and annihilationism. He delves into

More on OpenTheo

The Making of the American Mind with Matthew Spalding

Life and Books and Everything

February 2, 2026

The United States is unique in how much attention it pays to its founding, its founders, and its founding documents. Arguably, the most famous and mos

Conservatism and Religious Freedom with John Wilsey

Life and Books and Everything

October 27, 2025

What is conservatism? And why does it go hand in hand with religious freedom? How should we think about the American experiment of ordered liberty? Ha

How Do You Justify Calling Jesus the Messiah?

#STRask

December 18, 2025

Questions about how one can justify calling Jesus the Messiah when he didn’t fulfill the Hebrew messianic prophecies, and whether the reason for the v

Why Are So Many Christians Condemning LGB People Just Because of How They Love?

#STRask

January 15, 2026

Questions about Christians condemning LGB people just because of how they love, how God can expect someone to be celibate when others are free to marr

Is It a Sin to Feel Let Down by God?

#STRask

November 6, 2025

Questions about whether it’s a sin to feel let down by God and whether it would be easier to have a personal relationship with a rock than with a God

Why Does the Bible Teach You How to Be a Proper Slave Owner?

#STRask

November 13, 2025

Question about why it seems like the Bible teaches you how to be a proper slave owner rather than than saying, “Stop it. Give them freedom.”

* It s

Why Would Any Rational Person Have to Use Any Religious Book?

#STRask

December 8, 2025

Questions about why any rational person would have to use any religious book, whether apologetics would be redundant if there were actually a good, un

Is It Possible There’s a Being That’s Greater Than God?

#STRask

February 5, 2026

Questions about whether it’s possible there’s a being that’s greater than God and that’s outside of God’s comprehension and omniscience, and how to ex

How Would You Convince Someone That Evil Exists?

#STRask

November 17, 2025

Questions about how to convince someone that evil exists, whether Charlie Kirk’s murder was part of God’s plan, whether that would mean the murderer d

How Do I Determine Which Topics at Work Are Worth Commenting On?

#STRask

January 5, 2026

Questions about how to determine which topics at work are worth commenting on, and a good way to respond when you’re in a group Bible study and hear e

Christmas Cranks and Christmas Blessings with Justin Taylor and Collin Hansen

Life and Books and Everything

December 17, 2025

If you are looking for a podcast where three friends talk about whatever they want to talk about and ramble on about sports, books, and grievances, th

An Invitation to the 2026 Coram Deo Pastors Conference

Life and Books and Everything

February 18, 2026

"I love being a pastor, and I love pastors, which is why I hope you will consider joining us at the Coram Deo Pastors Conference in 2026." —Kevin DeYo

Prove to Me That Jesus Is Not a Created Being

#STRask

January 26, 2026

Questions about why we should think Jesus is not a created being, and what it means to say God became fully human if part of being human means not bei

Is 1 Corinthians 12:3 a Black-and-White Tool for Discernment?

#STRask

October 27, 2025

Questions about whether the claim in 1 Corinthians that “no one can say ‘Jesus is Lord’ except in the Holy Spirit” is a black-and-white tool for disce

What Are Some Good Ways to Start a Conversation About God with Family Members?

#STRask

October 30, 2025

Questions about how to start a conversation about God with non-Christian family members, how to keep from becoming emotional when discussing faith iss