Romes Truce with the Church

Church HistorySteve Gregg

In this talk, Steve Gregg discusses Rome's relationship with the Church during different periods in history, beginning with the persecution of Christians under Valerian and ending with Constantine's role in establishing Christianity as the official religion of the Roman Empire. Gregg highlights the intrusive nature of Constantine's involvement in church affairs, arguing that the emperor's legacy ultimately resulted in the infiltration of non-Christians into the Church. He emphasizes the importance of a changed heart and total surrender to Jesus as the foundation for true Christianity, instead of relying on legislative action or government support.

More from Church History

9 of 30

Next in this series

Defining Orthodoxy

Church History

In this talk, Steve Gregg discusses the history of the early Christian creeds and the concept of orthodoxy. He explains that the word "orthodoxy" come

10 of 30

Augustine's Influence and Contemporaries

Church History

Steve Gregg discusses the influence of Augustine and his contemporaries in this lecture. He touches on the debate between Pelagians and Augustinians r

7 of 30

Early Theologians

Church History

Steve Gregg discusses the rise of monasticism and the emergence of the earliest Christian theologians in the second to fourth centuries. He explains t

Series by Steve Gregg

Evangelism

Evangelism by Steve Gregg is a 6-part series that delves into the essence of evangelism and its role in discipleship, exploring the biblical foundatio

Philemon

Steve Gregg teaches a verse-by-verse study of the book of Philemon, examining the historical context and themes, and drawing insights from Paul's pray

Lamentations

Unveiling the profound grief and consequences of Jerusalem's destruction, Steve Gregg examines the book of Lamentations in a two-part series, delving

1 Samuel

In this 15-part series, Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the biblical book of 1 Samuel, examining the story of David's journey to becoming k

Ten Commandments

Steve Gregg delivers a thought-provoking and insightful lecture series on the relevance and importance of the Ten Commandments in modern times, delvin

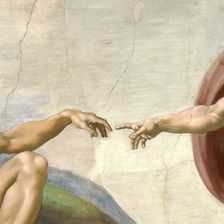

Creation and Evolution

In the series "Creation and Evolution" by Steve Gregg, the evidence against the theory of evolution is examined, questioning the scientific foundation

Deuteronomy

Steve Gregg provides a comprehensive and insightful commentary on the book of Deuteronomy, discussing the Israelites' relationship with God, the impor

2 Kings

In this 12-part series, Steve Gregg provides a thorough verse-by-verse analysis of the biblical book 2 Kings, exploring themes of repentance, reform,

2 Peter

This series features Steve Gregg teaching verse by verse through the book of 2 Peter, exploring topics such as false prophets, the importance of godli

Knowing God

Knowing God by Steve Gregg is a 16-part series that delves into the dynamics of relationships with God, exploring the importance of walking with Him,

More on OpenTheo

How Do You Justify Calling Jesus the Messiah?

#STRask

December 18, 2025

Questions about how one can justify calling Jesus the Messiah when he didn’t fulfill the Hebrew messianic prophecies, and whether the reason for the v

Is 1 Corinthians 12:3 a Black-and-White Tool for Discernment?

#STRask

October 27, 2025

Questions about whether the claim in 1 Corinthians that “no one can say ‘Jesus is Lord’ except in the Holy Spirit” is a black-and-white tool for disce

How Can I Explain Modesty to My Daughter?

#STRask

November 27, 2025

Questions about how to explain modesty to a nine-year-old in a way that won’t cause shame about her body, and when and how to tell a child about a pre

The Heidelberg Catechism with R. Scott Clark

Life and Books and Everything

November 3, 2025

You may not think you need 1,000 pages on the Heidelberg Catechism, but you do! R. Scott Clark, professor at Westminster Seminary California, has writ

Is Greg Placing His Faith in the Wrong Thing?

#STRask

February 12, 2026

Questions about Greg placing his faith in his personal assessment of which truth claims best match reality rather than in the revelation of God in Jes

Is It Possible There’s a Being That’s Greater Than God?

#STRask

February 5, 2026

Questions about whether it’s possible there’s a being that’s greater than God and that’s outside of God’s comprehension and omniscience, and how to ex

Why Would Any Rational Person Have to Use Any Religious Book?

#STRask

December 8, 2025

Questions about why any rational person would have to use any religious book, whether apologetics would be redundant if there were actually a good, un

Prove to Me That Jesus Is Not a Created Being

#STRask

January 26, 2026

Questions about why we should think Jesus is not a created being, and what it means to say God became fully human if part of being human means not bei

Shouldn’t I Be Praying for My Soul Rather Than for Material Things?

#STRask

February 2, 2026

Questions about whether we should be praying for our souls rather than for material things, why we need to pray about decisions, whether the devil can

Does Open-Mindedness Require Studying Other Religions Before Becoming a Christian?

#STRask

February 9, 2026

Questions about the claim that if Christians really want to be open-minded, they need to read and study other religions before committing to Christian

When I Can’t Stop Thinking About Something, Is That God Speaking?

#STRask

December 1, 2025

Questions about whether having a recurring thought is an indication God is speaking to you, what to say to someone who says they sinned because “God t

Did Jesus Prove He Wasn’t Sinless When He Overturned the Tables?

#STRask

December 29, 2025

Questions about whether Jesus proved he wasn’t sinless when he overturned the tables, whether Jesus’ response to the Pharisees in Mark 3:22–26 was a b

How Do I Determine Which Topics at Work Are Worth Commenting On?

#STRask

January 5, 2026

Questions about how to determine which topics at work are worth commenting on, and a good way to respond when you’re in a group Bible study and hear e

Conservatism and Religious Freedom with John Wilsey

Life and Books and Everything

October 27, 2025

What is conservatism? And why does it go hand in hand with religious freedom? How should we think about the American experiment of ordered liberty? Ha

Is It a Sin to Feel Let Down by God?

#STRask

November 6, 2025

Questions about whether it’s a sin to feel let down by God and whether it would be easier to have a personal relationship with a rock than with a God