Developments in the 20th Century

Church HistorySteve Gregg

Steve Gregg provides an overview of major religious movements and events that occurred throughout the 20th century. He highlights the rise of evangelicalism from fundamentalism, ongoing debates between modernism and fundamentalism, and the famous Scopes Trial that pitted creationism against evolution. Gregg also discusses key figures like Billy Graham, C.S. Lewis, and A.W. Tozer, who had significant influence in the evangelical movement through their writing and preaching. He concludes with a discussion on the Pentecostal and Charismatic movements, as well as the impact of the Jesus movement in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

More from Church History

29 of 30

Liberalism and Fundamentalism

Church History

In this discourse, Steve Gregg explores the emergence of liberalism and fundamentalism in Christianity during the 19th century. He suggests that liber

Series by Steve Gregg

Exodus

Steve Gregg's "Exodus" is a 25-part teaching series that delves into the book of Exodus verse by verse, covering topics such as the Ten Commandments,

1 Peter

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the book of 1 Peter, delving into themes of salvation, regeneration, Christian motivation, and the role of

Romans

Steve Gregg's 29-part series teaching verse by verse through the book of Romans, discussing topics such as justification by faith, reconciliation, and

God's Sovereignty and Man's Salvation

Steve Gregg explores the theological concepts of God's sovereignty and man's salvation, discussing topics such as unconditional election, limited aton

Content of the Gospel

"Content of the Gospel" by Steve Gregg is a comprehensive exploration of the transformative nature of the Gospel, emphasizing the importance of repent

2 Timothy

In this insightful series on 2 Timothy, Steve Gregg explores the importance of self-control, faith, and sound doctrine in the Christian life, urging b

Individual Topics

This is a series of over 100 lectures by Steve Gregg on various topics, including idolatry, friendships, truth, persecution, astrology, Bible study,

Survey of the Life of Christ

Steve Gregg's 9-part series explores various aspects of Jesus' life and teachings, including his genealogy, ministry, opposition, popularity, pre-exis

Philippians

In this 2-part series, Steve Gregg explores the book of Philippians, encouraging listeners to find true righteousness in Christ rather than relying on

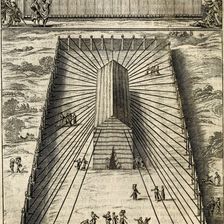

The Tabernacle

"The Tabernacle" is a comprehensive ten-part series that explores the symbolism and significance of the garments worn by priests, the construction and

More on OpenTheo

What Is the Role of the Holy Spirit in Our Lives if He Doesn’t Give Us Instructions?

#STRask

February 23, 2026

Questions about the role of the Holy Spirit in our lives, advice for someone who believes in God intellectually but struggles to understand how to hav

Could the Writers of Scripture Have Been Influenced by Their Fallen Nature?

#STRask

October 23, 2025

Questions about whether or not it’s reasonable to worry that some of our current doctrines were influenced by the fallen nature of the apostles, and h

How Would You Convince Someone That Evil Exists?

#STRask

November 17, 2025

Questions about how to convince someone that evil exists, whether Charlie Kirk’s murder was part of God’s plan, whether that would mean the murderer d

Does God Really Need a “Pound of Flesh” to Forgive Sins?

#STRask

January 12, 2026

Questions about how to answer the challenge that God doesn’t need a “pound of flesh” to forgive sins but can simply forgive, and whether the claim in

Sense, Sensibility, and Adam Smith with Jan Van Vliet

Life and Books and Everything

February 16, 2026

This year is a special anniversary for the United States as Americans celebrate 250 years of independence. But 1776 was an important year in more ways

What Do You Think About Churches Advertising on Social Media?

#STRask

January 19, 2026

Questions about whether there’s an issue with churches advertising on social media, whether it’s weird if we pray along with a YouTuber, and whether C

Keri Ingraham: School Choice and Education Reform

Knight & Rose Show

January 24, 2026

Wintery Knight and guest host Bonnie welcome Dr. Keri Ingraham to discuss school choice and education reform. They discuss the public school monopoly'

The Resurrection Standoff: Licona vs. Ehrman on the Unbelievable Podcast

Risen Jesus

October 22, 2025

This episode is taken from the Unbelievable podcast with Justin Brierly in 2011 when Dr. Bart Ehrman and Dr. Michael Licona address the question: Is t

Christmas Cranks and Christmas Blessings with Justin Taylor and Collin Hansen

Life and Books and Everything

December 17, 2025

If you are looking for a podcast where three friends talk about whatever they want to talk about and ramble on about sports, books, and grievances, th

Kingdom Priorities: Following the Teachings of Jesus

Knight & Rose Show

February 14, 2026

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose discuss Jesus' teachings from the Gospels, emphasizing truth, evidence, self-denial, and forgiveness. They explore pass

Shouldn’t I Be Praying for My Soul Rather Than for Material Things?

#STRask

February 2, 2026

Questions about whether we should be praying for our souls rather than for material things, why we need to pray about decisions, whether the devil can

Can Two Logical People Come to Conflicting Conclusions Without Committing a Fallacy?

#STRask

January 8, 2026

Questions about whether two logical people can come to conflicting conclusions on a topic without committing a fallacy, how Greg, as a public figure,

Why Would Any Rational Person Have to Use Any Religious Book?

#STRask

December 8, 2025

Questions about why any rational person would have to use any religious book, whether apologetics would be redundant if there were actually a good, un

Are Demon Possessions and Exorcisms in the New Testament Literal?

#STRask

December 11, 2025

Questions about whether references to demon possessions and exorcisms in the New Testament are literal, how to talk to young children about ghosts, an

The Making of the American Mind with Matthew Spalding

Life and Books and Everything

February 2, 2026

The United States is unique in how much attention it pays to its founding, its founders, and its founding documents. Arguably, the most famous and mos