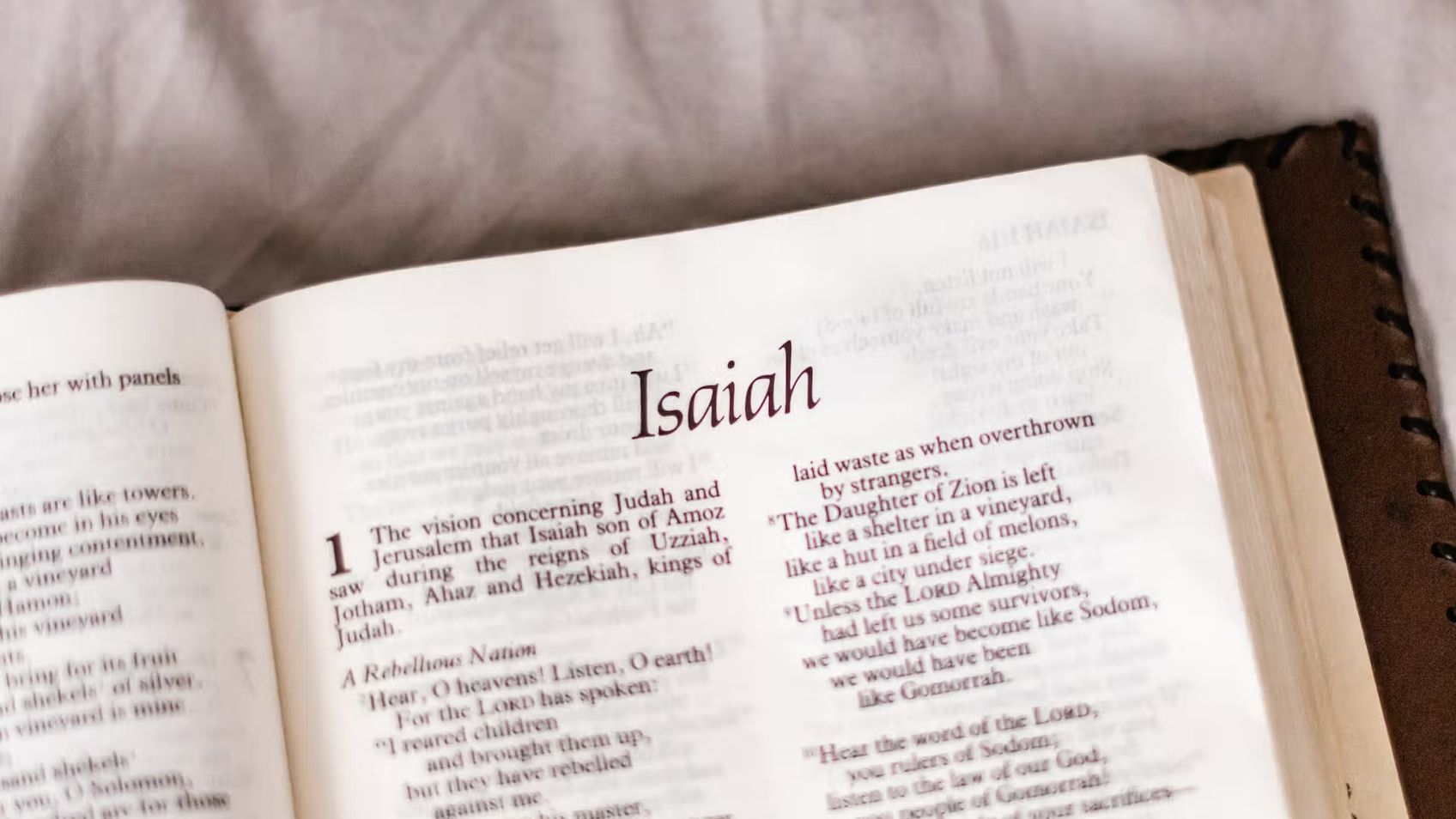

Isaiah - Isaiah Redemption

IsaiahSteve Gregg

The book of Isaiah is a rare example of Old Testament literature that remains wholly relevant to Christians today, says biblical scholar Steve Gregg. Its themes of redemption and salvation through Christ are intertwined with the story of Exodus and the Babylonian exile, offering valuable insight into the history of God's people. Gregg delves into specific verses from Isaiah, highlighting their importance both to the apostles in the New Testament and to modern readers seeking spiritual guidance.

More from Isaiah

9 of 32

Next in this series

Isaiah - The Second Exodus

Isaiah

Explore the theme of deliverance from bondage in the book of Isaiah with Steve Gregg, as he discusses various aspects of the Exodus motif and how it a

10 of 32

Isaiah - Return from Exile

Isaiah

Isaiah prophesied about the return of Israel from their exile and their re-establishment as God's chosen people. The message of the gospel, that there

7 of 32

Isaiah - Warfare and Judgment

Isaiah

Steve Gregg offers a unique perspective on the Book of Isaiah, exploring its themes of warfare and judgment through a spiritual lens. He discusses the

Series by Steve Gregg

Making Sense Out Of Suffering

In "Making Sense Out Of Suffering," Steve Gregg delves into the philosophical question of why a good sovereign God allows suffering in the world.

Content of the Gospel

"Content of the Gospel" by Steve Gregg is a comprehensive exploration of the transformative nature of the Gospel, emphasizing the importance of repent

1 Timothy

In this 8-part series, Steve Gregg provides in-depth teachings, insights, and practical advice on the book of 1 Timothy, covering topics such as the r

The Beatitudes

Steve Gregg teaches through the Beatitudes in Jesus' Sermon on the Mount.

Strategies for Unity

"Strategies for Unity" is a 4-part series discussing the importance of Christian unity, overcoming division, promoting positive relationships, and pri

Philippians

In this 2-part series, Steve Gregg explores the book of Philippians, encouraging listeners to find true righteousness in Christ rather than relying on

Zephaniah

Experience the prophetic words of Zephaniah, written in 612 B.C., as Steve Gregg vividly brings to life the impending judgement, destruction, and hope

Numbers

Steve Gregg's series on the book of Numbers delves into its themes of leadership, rituals, faith, and guidance, aiming to uncover timeless lessons and

Psalms

In this 32-part series, Steve Gregg provides an in-depth verse-by-verse analysis of various Psalms, highlighting their themes, historical context, and

Haggai

In Steve Gregg's engaging exploration of the book of Haggai, he highlights its historical context and key themes often overlooked in this prophetic wo

More on OpenTheo

Conservatism and Religious Freedom with John Wilsey

Life and Books and Everything

October 27, 2025

What is conservatism? And why does it go hand in hand with religious freedom? How should we think about the American experiment of ordered liberty? Ha

Could the Writers of Scripture Have Been Influenced by Their Fallen Nature?

#STRask

October 23, 2025

Questions about whether or not it’s reasonable to worry that some of our current doctrines were influenced by the fallen nature of the apostles, and h

How Do I Determine Which Topics at Work Are Worth Commenting On?

#STRask

January 5, 2026

Questions about how to determine which topics at work are worth commenting on, and a good way to respond when you’re in a group Bible study and hear e

Why Should We Pray If God Already Knows What’s Going to Happen?

#STRask

January 29, 2026

Questions about why we should pray if God already knows what’s going to happen, how the effectiveness of prayer is measured, and whether or not things

Did God Create Us So He Wouldn’t Be Alone?

#STRask

November 3, 2025

Questions about whether God created us so he wouldn’t be alone, what he had before us, and a comparison between the Muslim view of God and the Christi

Shouldn’t I Be Praying for My Soul Rather Than for Material Things?

#STRask

February 2, 2026

Questions about whether we should be praying for our souls rather than for material things, why we need to pray about decisions, whether the devil can

Did Jesus Prove He Wasn’t Sinless When He Overturned the Tables?

#STRask

December 29, 2025

Questions about whether Jesus proved he wasn’t sinless when he overturned the tables, whether Jesus’ response to the Pharisees in Mark 3:22–26 was a b

The Heidelberg Catechism with R. Scott Clark

Life and Books and Everything

November 3, 2025

You may not think you need 1,000 pages on the Heidelberg Catechism, but you do! R. Scott Clark, professor at Westminster Seminary California, has writ

How Would You Convince Someone That Evil Exists?

#STRask

November 17, 2025

Questions about how to convince someone that evil exists, whether Charlie Kirk’s murder was part of God’s plan, whether that would mean the murderer d

Prove to Me That Jesus Is Not a Created Being

#STRask

January 26, 2026

Questions about why we should think Jesus is not a created being, and what it means to say God became fully human if part of being human means not bei

Does God Hear the Prayers of Non-Believers?

#STRask

February 26, 2026

Questions about whether or not God hears and answers the prayers of non-believers, and thoughts about a church sign that reads (as if from God), “Just

Lora Ries: Border Security and Immigration Policy

Knight & Rose Show

December 7, 2025

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose welcome Lora Ries to discuss border security and immigration policy. They explore Biden's policy changes, like ending R

What Tools of Reasoning Help You Know What’s True, Right, and Good?

#STRask

December 4, 2025

Question about what tools of reasoning help us determine whether something is true or false, right or wrong, good or bad before bringing Scripture int

E. Calvin Beisner: Climate and Energy Policy

Knight & Rose Show

January 4, 2026

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose welcome Dr. E. Calvin Beisner to discuss climate and energy policy. They explore Biblical dominion and stewardship, con

The Man on the Middle Cross with Alistair Begg

Life and Books and Everything

November 10, 2025

If you haven’t seen the viral clip, go see it right now. In this episode, Kevin talks to Alistair about the preaching clip he didn’t intend to give, h