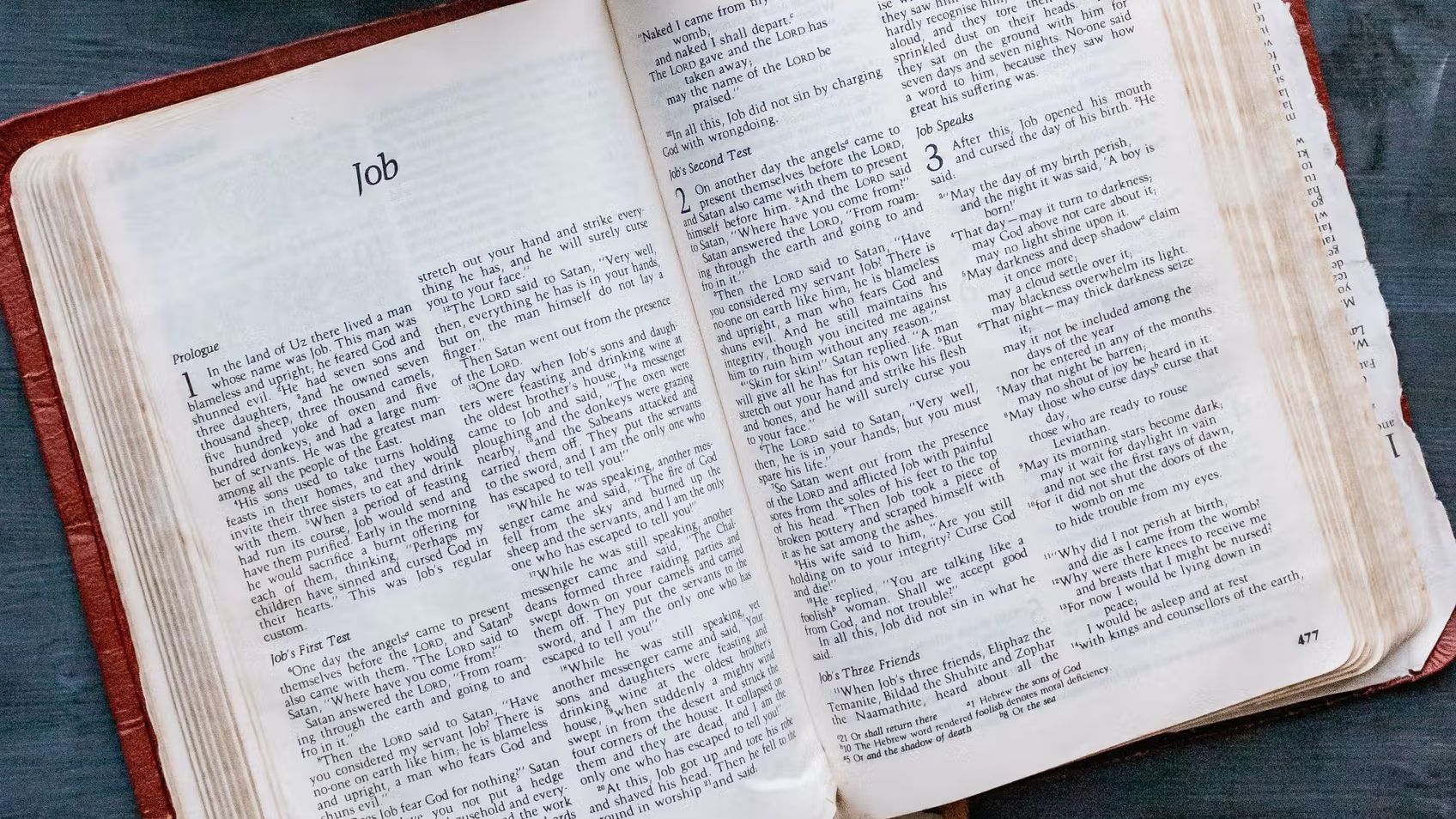

Job 29 - 31

JobSteve Gregg

In "Job 29-31," Steve Gregg explores Job's final speech in these chapters. Job reflects on the importance of fearing the Lord and realizing the terror of rebelling against God. He also speaks of his past blessings and the sorrow he currently faces. Gregg analyzes Eliphaz's response to Job and the rhetorical device of "if-then" statements used in the chapter. Gregg concludes that while Job may not be a perfect man, he is still an example of humility to learn from.

More from Job

10 of 11

Next in this series

Job 32 - 37

Job

In this segment, Steve Gregg discusses Elihu's speeches in Job chapters 32-37. Elihu is presented as a young man with a fresh perspective, who becomes

11 of 11

Job 38 - 42

Job

The section of the book of Job, chapters 38 - 42, features God speaking to Job in passing references. The exact message God conveys to Job remains unk

8 of 11

Job 23 - 28

Job

In this talk, Steve Gregg provides insights on Job 23 - 28. Job discusses how he cannot see God, but God sees him, and that he treasures God's word as

Series by Steve Gregg

Zechariah

Steve Gregg provides a comprehensive guide to the book of Zechariah, exploring its historical context, prophecies, and symbolism through ten lectures.

Content of the Gospel

"Content of the Gospel" by Steve Gregg is a comprehensive exploration of the transformative nature of the Gospel, emphasizing the importance of repent

1 Kings

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the book of 1 Kings, providing insightful commentary on topics such as discernment, building projects, the

Message For The Young

In this 6-part series, Steve Gregg emphasizes the importance of pursuing godliness and avoiding sinful behavior as a Christian, encouraging listeners

Authority of Scriptures

Steve Gregg teaches on the authority of the Scriptures.

The Narrow Path is the radio and internet ministry of Steve Gregg, a servant Bible teacher to

Philippians

In this 2-part series, Steve Gregg explores the book of Philippians, encouraging listeners to find true righteousness in Christ rather than relying on

Joshua

Steve Gregg's 13-part series on the book of Joshua provides insightful analysis and application of key themes including spiritual warfare, obedience t

Ruth

Steve Gregg provides insightful analysis on the biblical book of Ruth, exploring its historical context, themes of loyalty and redemption, and the cul

Cultivating Christian Character

Steve Gregg's lecture series focuses on cultivating holiness and Christian character, emphasizing the need to have God's character and to walk in the

Zephaniah

Experience the prophetic words of Zephaniah, written in 612 B.C., as Steve Gregg vividly brings to life the impending judgement, destruction, and hope

More on OpenTheo

How Do You Justify Calling Jesus the Messiah?

#STRask

December 18, 2025

Questions about how one can justify calling Jesus the Messiah when he didn’t fulfill the Hebrew messianic prophecies, and whether the reason for the v

Why Do We Say Someone Was Saved on a Particular Date If It Was Part of an Eternal Plan?

#STRask

November 24, 2025

Questions about why we say someone was saved on a particular date if it was part of an eternal plan, the Roman Catholic view of the gospel vs. the Bib

Is Greg Placing His Faith in the Wrong Thing?

#STRask

February 12, 2026

Questions about Greg placing his faith in his personal assessment of which truth claims best match reality rather than in the revelation of God in Jes

Does God Hear the Prayers of Non-Believers?

#STRask

February 26, 2026

Questions about whether or not God hears and answers the prayers of non-believers, and thoughts about a church sign that reads (as if from God), “Just

E. Calvin Beisner: Climate and Energy Policy

Knight & Rose Show

January 4, 2026

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose welcome Dr. E. Calvin Beisner to discuss climate and energy policy. They explore Biblical dominion and stewardship, con

Why Is It Necessary to Believe Jesus Is God?

#STRask

February 19, 2026

Questions about why it’s necessary to believe Jesus is God, whether belief in the Trinity is required for salvation, and why one has to believe in the

What Are Some Good Ways to Start a Conversation About God with Family Members?

#STRask

October 30, 2025

Questions about how to start a conversation about God with non-Christian family members, how to keep from becoming emotional when discussing faith iss

Is 1 Corinthians 12:3 a Black-and-White Tool for Discernment?

#STRask

October 27, 2025

Questions about whether the claim in 1 Corinthians that “no one can say ‘Jesus is Lord’ except in the Holy Spirit” is a black-and-white tool for disce

Can Two Logical People Come to Conflicting Conclusions Without Committing a Fallacy?

#STRask

January 8, 2026

Questions about whether two logical people can come to conflicting conclusions on a topic without committing a fallacy, how Greg, as a public figure,

Is It Possible There’s a Being That’s Greater Than God?

#STRask

February 5, 2026

Questions about whether it’s possible there’s a being that’s greater than God and that’s outside of God’s comprehension and omniscience, and how to ex

Did Jesus Prove He Wasn’t Sinless When He Overturned the Tables?

#STRask

December 29, 2025

Questions about whether Jesus proved he wasn’t sinless when he overturned the tables, whether Jesus’ response to the Pharisees in Mark 3:22–26 was a b

Why Would Any Rational Person Have to Use Any Religious Book?

#STRask

December 8, 2025

Questions about why any rational person would have to use any religious book, whether apologetics would be redundant if there were actually a good, un

How Do We Advocate for Christian Policy Without Making the Government Interfere in Every Area of Life?

#STRask

November 20, 2025

Questions about how to advocate for Christian policy without making the government interfere in every area of life, and the differences between the mo

What Tools of Reasoning Help You Know What’s True, Right, and Good?

#STRask

December 4, 2025

Question about what tools of reasoning help us determine whether something is true or false, right or wrong, good or bad before bringing Scripture int

What Is Wrong with Wokeness? With Neil Shenvi

Life and Books and Everything

January 19, 2026

In this timely interview, Kevin talks to Neil Shenvi about his new book (co-authored with Pat Sawyer), entitled “Post Woke: Asserting a Biblical Visio