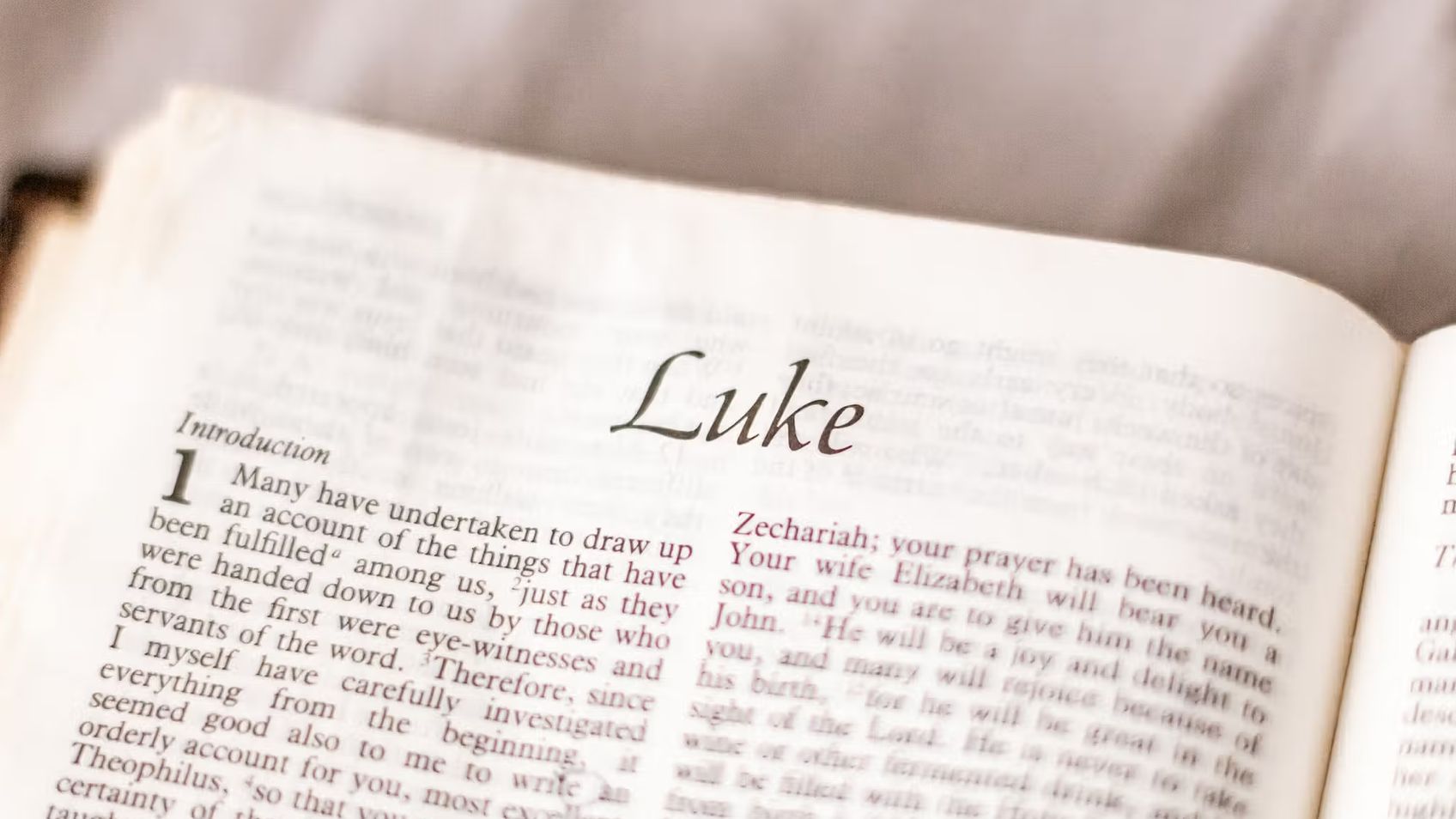

Luke 16:19 - 16:31

Gospel of LukeSteve Gregg

In this segment, Steve Gregg analyzes Luke 16:19-31, where Jesus tells a parable about a wealthy man and a poor man named Lazarus who dies and goes to Abraham's bosom while the wealthy man goes to Hades. Gregg argues that the parable is not meant to be a teaching on the afterlife but rather a commentary on the obstinance of the Jews in rejecting the law and the prophets even after Jesus rose from the dead. He also emphasizes Luke's gospel as being favorable toward the poor and providing strict warnings for the privileged rich.

More from Gospel of Luke

23 of 32

Next in this series

Luke 17

Gospel of Luke

In Luke 17, Steve Gregg discusses the idea that stumbling is inevitable in life, though it does not necessarily indicate sin. However, causing someone

24 of 32

Luke 18:1 - 18:23

Gospel of Luke

In this talk, Steve Gregg provides an analysis of Luke 18:1-23, discussing the importance of persistence in prayer and humility before God. He uses th

21 of 32

Luke 16:1 - 16:18

Gospel of Luke

In this discussion, Steve Gregg examines Luke 16:1-18, which includes the parable of the unjust steward. He suggests that the steward's actions were n

Series by Steve Gregg

Haggai

In Steve Gregg's engaging exploration of the book of Haggai, he highlights its historical context and key themes often overlooked in this prophetic wo

Isaiah: A Topical Look At Isaiah

In this 15-part series, Steve Gregg examines the key themes and ideas that recur throughout the book of Isaiah, discussing topics such as the remnant,

Kingdom of God

An 8-part series by Steve Gregg that explores the concept of the Kingdom of God and its various aspects, including grace, priesthood, present and futu

Micah

Steve Gregg provides a verse-by-verse analysis and teaching on the book of Micah, exploring the prophet's prophecies of God's judgment, the birthplace

2 Samuel

Steve Gregg provides a verse-by-verse analysis of the book of 2 Samuel, focusing on themes, characters, and events and their relevance to modern-day C

Gospel of John

In this 38-part series, Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the Gospel of John, providing insightful analysis and exploring important themes su

Content of the Gospel

"Content of the Gospel" by Steve Gregg is a comprehensive exploration of the transformative nature of the Gospel, emphasizing the importance of repent

Song of Songs

Delve into the allegorical meanings of the biblical Song of Songs and discover the symbolism, themes, and deeper significance with Steve Gregg's insig

1 Peter

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the book of 1 Peter, delving into themes of salvation, regeneration, Christian motivation, and the role of

Toward a Radically Christian Counterculture

Steve Gregg presents a vision for building a distinctive and holy Christian culture that stands in opposition to the values of the surrounding secular

More on OpenTheo

What Do You Think About Churches Advertising on Social Media?

#STRask

January 19, 2026

Questions about whether there’s an issue with churches advertising on social media, whether it’s weird if we pray along with a YouTuber, and whether C

Conservatism and Religious Freedom with John Wilsey

Life and Books and Everything

October 27, 2025

What is conservatism? And why does it go hand in hand with religious freedom? How should we think about the American experiment of ordered liberty? Ha

How Do I Reconcile the Image of God as Judge with His Love, Grace, and Kindness?

#STRask

October 20, 2025

Questions about how to reconcile the image of God as a judge with his love, grace, and kindness, why our sins are considered to be sins against God, a

Is 1 Corinthians 12:3 a Black-and-White Tool for Discernment?

#STRask

October 27, 2025

Questions about whether the claim in 1 Corinthians that “no one can say ‘Jesus is Lord’ except in the Holy Spirit” is a black-and-white tool for disce

Do Christians Need to Believe that Jesus was Raised Bodily from the Dead? Licona vs. Patterson

Risen Jesus

October 15, 2025

In this episode, Dr. Stephen Patterson, New Testament professor at Eden Theological Seminary, argues against the bodily resurrection of Jesus, contend

Could the Writers of Scripture Have Been Influenced by Their Fallen Nature?

#STRask

October 23, 2025

Questions about whether or not it’s reasonable to worry that some of our current doctrines were influenced by the fallen nature of the apostles, and h

The Resurrection Standoff: Licona vs. Ehrman on the Unbelievable Podcast

Risen Jesus

October 22, 2025

This episode is taken from the Unbelievable podcast with Justin Brierly in 2011 when Dr. Bart Ehrman and Dr. Michael Licona address the question: Is t

E. Calvin Beisner: Climate and Energy Policy

Knight & Rose Show

January 4, 2026

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose welcome Dr. E. Calvin Beisner to discuss climate and energy policy. They explore Biblical dominion and stewardship, con

Does God Really Need a “Pound of Flesh” to Forgive Sins?

#STRask

January 12, 2026

Questions about how to answer the challenge that God doesn’t need a “pound of flesh” to forgive sins but can simply forgive, and whether the claim in

When I Can’t Stop Thinking About Something, Is That God Speaking?

#STRask

December 1, 2025

Questions about whether having a recurring thought is an indication God is speaking to you, what to say to someone who says they sinned because “God t

How Does It Affect You If a Gay Couple Gets Married or a Woman Has an Abortion?

#STRask

October 16, 2025

Questions about how to respond to someone who asks, ”How does it affect you if a gay couple gets married, or a woman makes a decision about her reprod

What Is Wrong with Wokeness? With Neil Shenvi

Life and Books and Everything

January 19, 2026

In this timely interview, Kevin talks to Neil Shenvi about his new book (co-authored with Pat Sawyer), entitled “Post Woke: Asserting a Biblical Visio

What Tools of Reasoning Help You Know What’s True, Right, and Good?

#STRask

December 4, 2025

Question about what tools of reasoning help us determine whether something is true or false, right or wrong, good or bad before bringing Scripture int

How Can I Explain Modesty to My Daughter?

#STRask

November 27, 2025

Questions about how to explain modesty to a nine-year-old in a way that won’t cause shame about her body, and when and how to tell a child about a pre

Why Do We Say Someone Was Saved on a Particular Date If It Was Part of an Eternal Plan?

#STRask

November 24, 2025

Questions about why we say someone was saved on a particular date if it was part of an eternal plan, the Roman Catholic view of the gospel vs. the Bib