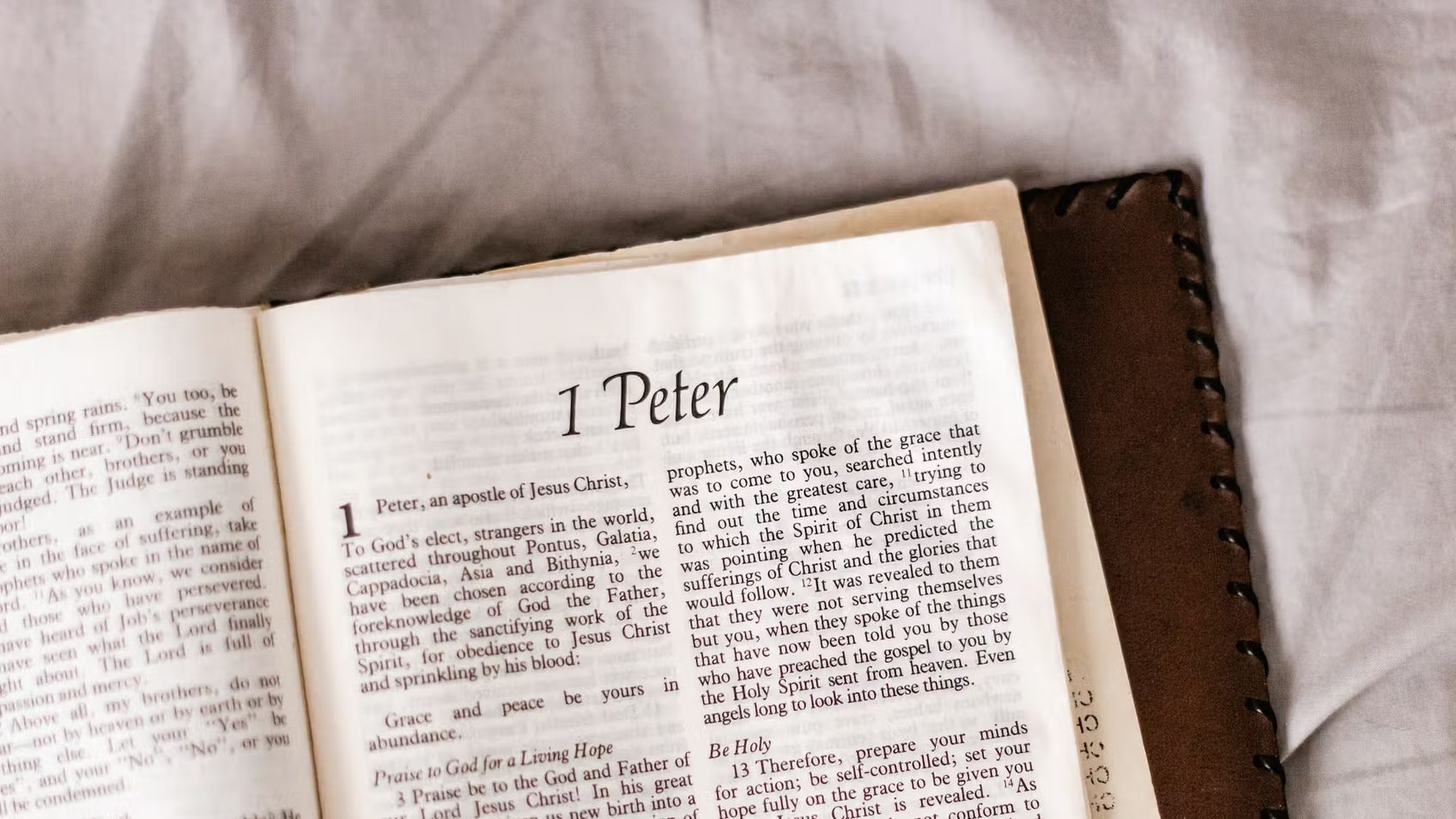

1 Peter Introduction (Part 2)

1 PeterSteve Gregg

Steve Gregg delves into the context of 1 Peter in the second part of his introduction. He suggests that the fiery trials mentioned in chapter 4 may have been related to Nero's persecution of Christians, which some argue did not reach Asia at the time this letter was written. He also explores the use of the term "pilgrims" to refer to the dispersed Christians who were living in Gentile lands, and highlights the similarities between the teachings in 1 Peter and the words of Jesus. With a focus on the suffering and conduct of believers, the letter addresses theological points that serve as an opening to the subject matter.

More from 1 Peter

3 of 12

Next in this series

1 Peter 1:1 - 1:2

1 Peter

Steve Gregg provides an outline of the book of 1 Peter, which gives practical advice on Christian behavior based on Christian beliefs. The letter addr

4 of 12

1 Peter 1:3 - 1:12

1 Peter

In this commentary, Steve Gregg delves into 1 Peter 1:3-12, examining themes of salvation, regeneration, and Christian motivation. He affirms that sal

1 of 12

1 Peter Introduction (Part 1)

1 Peter

In this introduction to 1 Peter, Steve Gregg discusses the importance of Peter in the early church and his relationship with Christ, as well as the qu

Series by Steve Gregg

The Jewish Roots Movement

"The Jewish Roots Movement" by Steve Gregg is a six-part series that explores Paul's perspective on Torah observance, the distinction between Jewish a

Ephesians

In this 10-part series, Steve Gregg provides verse by verse teachings and insights through the book of Ephesians, emphasizing themes such as submissio

Micah

Steve Gregg provides a verse-by-verse analysis and teaching on the book of Micah, exploring the prophet's prophecies of God's judgment, the birthplace

Ten Commandments

Steve Gregg delivers a thought-provoking and insightful lecture series on the relevance and importance of the Ten Commandments in modern times, delvin

Nehemiah

A comprehensive analysis by Steve Gregg on the book of Nehemiah, exploring the story of an ordinary man's determination and resilience in rebuilding t

Gospel of Matthew

Spanning 72 hours of teaching, Steve Gregg's verse by verse teaching through the Gospel of Matthew provides a thorough examination of Jesus' life and

Genuinely Following Jesus

Steve Gregg's lecture series on discipleship emphasizes the importance of following Jesus and becoming more like Him in character and values. He highl

James

A five-part series on the book of James by Steve Gregg focuses on practical instructions for godly living, emphasizing the importance of using words f

Charisma and Character

In this 16-part series, Steve Gregg discusses various gifts of the Spirit, including prophecy, joy, peace, and humility, and emphasizes the importance

1 John

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the book of 1 John, providing commentary and insights on topics such as walking in the light and love of Go

More on OpenTheo

Lora Ries: Border Security and Immigration Policy

Knight & Rose Show

December 7, 2025

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose welcome Lora Ries to discuss border security and immigration policy. They explore Biden's policy changes, like ending R

Conservatism and Religious Freedom with John Wilsey

Life and Books and Everything

October 27, 2025

What is conservatism? And why does it go hand in hand with religious freedom? How should we think about the American experiment of ordered liberty? Ha

Did God Create Us So He Wouldn’t Be Alone?

#STRask

November 3, 2025

Questions about whether God created us so he wouldn’t be alone, what he had before us, and a comparison between the Muslim view of God and the Christi

Why Does the Bible Teach You How to Be a Proper Slave Owner?

#STRask

November 13, 2025

Question about why it seems like the Bible teaches you how to be a proper slave owner rather than than saying, “Stop it. Give them freedom.”

* It s

The Heidelberg Catechism with R. Scott Clark

Life and Books and Everything

November 3, 2025

You may not think you need 1,000 pages on the Heidelberg Catechism, but you do! R. Scott Clark, professor at Westminster Seminary California, has writ

Why Should We Pray If God Already Knows What’s Going to Happen?

#STRask

January 29, 2026

Questions about why we should pray if God already knows what’s going to happen, how the effectiveness of prayer is measured, and whether or not things

Protestants and Catholics: What’s the Difference? With Chad Van Dixhoorn, Blair Smith, and Mark McDowell

Life and Books and Everything

November 26, 2025

How should Protestants think about the Catholic Mass? About the Eucharist? About the history and development of the papacy? In this panel discussion,

Christmas Cranks and Christmas Blessings with Justin Taylor and Collin Hansen

Life and Books and Everything

December 17, 2025

If you are looking for a podcast where three friends talk about whatever they want to talk about and ramble on about sports, books, and grievances, th

Are You Accursed If You Tithe?

#STRask

December 15, 2025

Questions about whether anyone who tithes is not a Christian and is accursed since Paul says that if you obey one part of the Mosaic Law you’re obliga

What About Those Who Never Heard the Name of Jesus?

#STRask

December 22, 2025

Questions about what will happen to those who never heard of Jesus or were brought up in a different faith, whether there’s biblical warrant to think

Sense, Sensibility, and Adam Smith with Jan Van Vliet

Life and Books and Everything

February 16, 2026

This year is a special anniversary for the United States as Americans celebrate 250 years of independence. But 1776 was an important year in more ways

Why Would Any Rational Person Have to Use Any Religious Book?

#STRask

December 8, 2025

Questions about why any rational person would have to use any religious book, whether apologetics would be redundant if there were actually a good, un

Shouldn’t I Be Praying for My Soul Rather Than for Material Things?

#STRask

February 2, 2026

Questions about whether we should be praying for our souls rather than for material things, why we need to pray about decisions, whether the devil can

When I Can’t Stop Thinking About Something, Is That God Speaking?

#STRask

December 1, 2025

Questions about whether having a recurring thought is an indication God is speaking to you, what to say to someone who says they sinned because “God t

The Resurrection Standoff: Licona vs. Ehrman on the Unbelievable Podcast

Risen Jesus

October 22, 2025

This episode is taken from the Unbelievable podcast with Justin Brierly in 2011 when Dr. Bart Ehrman and Dr. Michael Licona address the question: Is t