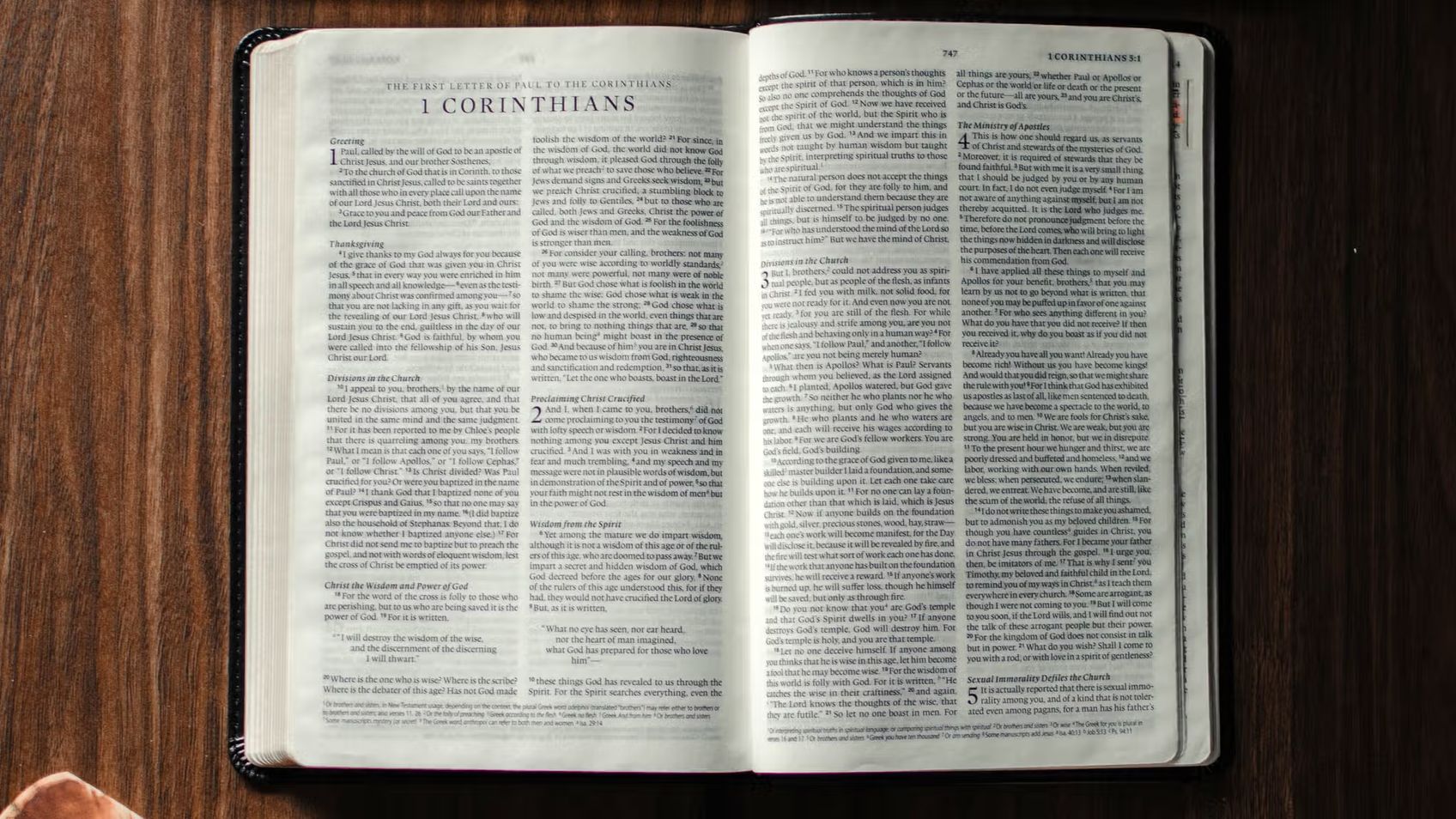

1 Corinthians 11:14 - 34

1 CorinthiansSteve Gregg

In this session, Steve Gregg focuses on the latter half of 1 Corinthians 11, which addresses various forms of disorder and misbehavior in Corinthian worship services. The discussion covers the biblical symbolism of a woman's head covering, the importance of modesty, and the need for self-examination during communal meals such as the Lord's Supper. Overall, Gregg emphasizes the importance of correcting problematic behavior within the church rather than dividing and starting new congregations.

More from 1 Corinthians

13 of 17

Next in this series

1 Corinthians 12:1 - 10

1 Corinthians

Steve Gregg discusses 1 Corinthians 12-14, which are often cited to support the idea of supernatural gifts in the Church. While acknowledging the vali

14 of 17

1 Corinthians 12:10 - 31

1 Corinthians

The book of 1 Corinthians, specifically chapters 12-14, puts spiritual gifts in proper perspective by emphasizing the importance of love and concern f

11 of 17

1 Corinthians 11:1 - 16

1 Corinthians

In this text, Steve Gregg explores the complex and multi-layered themes of 1 Corinthians 11:1-16. He discusses the importance of laying down personal

Series by Steve Gregg

Spiritual Warfare

In "Spiritual Warfare," Steve Gregg explores the tactics of the devil, the methods to resist Satan's devices, the concept of demonic possession, and t

Philemon

Steve Gregg teaches a verse-by-verse study of the book of Philemon, examining the historical context and themes, and drawing insights from Paul's pray

Acts

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the book of Acts, providing insights on the early church, the actions of the apostles, and the mission to s

Colossians

In this 8-part series from Steve Gregg, listeners are taken on an insightful journey through the book of Colossians, exploring themes of transformatio

What Are We to Make of Israel

Steve Gregg explores the intricate implications of certain biblical passages in relation to the future of Israel, highlighting the historical context,

Judges

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the Book of Judges in this 16-part series, exploring its historical and cultural context and highlighting t

Revelation

In this 19-part series, Steve Gregg offers a verse-by-verse analysis of the book of Revelation, discussing topics such as heavenly worship, the renewa

What You Absolutely Need To Know Before You Get Married

Steve Gregg's lecture series on marriage emphasizes the gravity of the covenant between two individuals and the importance of understanding God's defi

2 Thessalonians

A thought-provoking biblical analysis by Steve Gregg on 2 Thessalonians, exploring topics such as the concept of rapture, martyrdom in church history,

Gospel of Matthew

Spanning 72 hours of teaching, Steve Gregg's verse by verse teaching through the Gospel of Matthew provides a thorough examination of Jesus' life and

More on OpenTheo

The Making of the American Mind with Matthew Spalding

Life and Books and Everything

February 2, 2026

The United States is unique in how much attention it pays to its founding, its founders, and its founding documents. Arguably, the most famous and mos

Why Should We Pray If God Already Knows What’s Going to Happen?

#STRask

January 29, 2026

Questions about why we should pray if God already knows what’s going to happen, how the effectiveness of prayer is measured, and whether or not things

Protestants and Catholics: What’s the Difference? With Chad Van Dixhoorn, Blair Smith, and Mark McDowell

Life and Books and Everything

November 26, 2025

How should Protestants think about the Catholic Mass? About the Eucharist? About the history and development of the papacy? In this panel discussion,

Does God Hear the Prayers of Non-Believers?

#STRask

February 26, 2026

Questions about whether or not God hears and answers the prayers of non-believers, and thoughts about a church sign that reads (as if from God), “Just

Why Are So Many Christians Condemning LGB People Just Because of How They Love?

#STRask

January 15, 2026

Questions about Christians condemning LGB people just because of how they love, how God can expect someone to be celibate when others are free to marr

Why Do We Say Someone Was Saved on a Particular Date If It Was Part of an Eternal Plan?

#STRask

November 24, 2025

Questions about why we say someone was saved on a particular date if it was part of an eternal plan, the Roman Catholic view of the gospel vs. the Bib

What Do You Think About Churches Advertising on Social Media?

#STRask

January 19, 2026

Questions about whether there’s an issue with churches advertising on social media, whether it’s weird if we pray along with a YouTuber, and whether C

How Do We Advocate for Christian Policy Without Making the Government Interfere in Every Area of Life?

#STRask

November 20, 2025

Questions about how to advocate for Christian policy without making the government interfere in every area of life, and the differences between the mo

What Is the Role of the Holy Spirit in Our Lives if He Doesn’t Give Us Instructions?

#STRask

February 23, 2026

Questions about the role of the Holy Spirit in our lives, advice for someone who believes in God intellectually but struggles to understand how to hav

Conservatism and Religious Freedom with John Wilsey

Life and Books and Everything

October 27, 2025

What is conservatism? And why does it go hand in hand with religious freedom? How should we think about the American experiment of ordered liberty? Ha

An Invitation to the 2026 Coram Deo Pastors Conference

Life and Books and Everything

February 18, 2026

"I love being a pastor, and I love pastors, which is why I hope you will consider joining us at the Coram Deo Pastors Conference in 2026." —Kevin DeYo

What About Those Who Never Heard the Name of Jesus?

#STRask

December 22, 2025

Questions about what will happen to those who never heard of Jesus or were brought up in a different faith, whether there’s biblical warrant to think

The Man on the Middle Cross with Alistair Begg

Life and Books and Everything

November 10, 2025

If you haven’t seen the viral clip, go see it right now. In this episode, Kevin talks to Alistair about the preaching clip he didn’t intend to give, h

Is It Possible There’s a Being That’s Greater Than God?

#STRask

February 5, 2026

Questions about whether it’s possible there’s a being that’s greater than God and that’s outside of God’s comprehension and omniscience, and how to ex

Did Jesus Prove He Wasn’t Sinless When He Overturned the Tables?

#STRask

December 29, 2025

Questions about whether Jesus proved he wasn’t sinless when he overturned the tables, whether Jesus’ response to the Pharisees in Mark 3:22–26 was a b