Matthew Introduction (Part 3)

Gospel of MatthewSteve Gregg

In this introduction to the Gospel of Matthew, Steve Gregg discusses the authorship, composition, and style of the first book of the New Testament. He notes that the book is likely written by the disciple Matthew, a former tax collector who was called by Jesus to follow him. Gregg also highlights Matthew's use of Aramaic and his sensitivity to Jewish customs in his writing, as well as how Matthew's arrangement of Jesus' teachings differs from the Gospels of Mark and Luke.

More from Gospel of Matthew

4 of 197

Next in this series

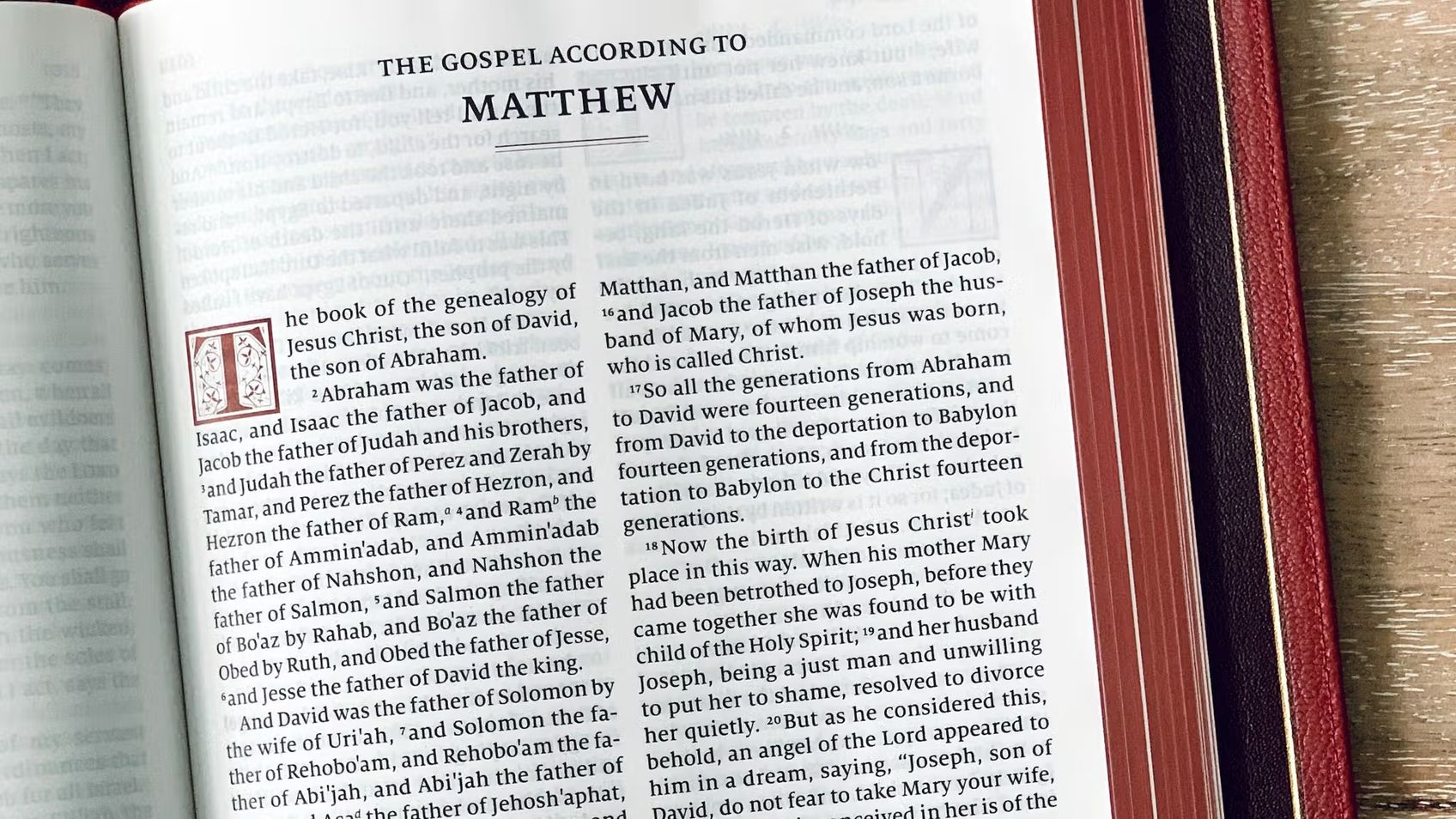

Matthew 1:1 - 1:17

Gospel of Matthew

In this teaching, Steve Gregg dives into the importance of Jesus' genealogy in Matthew 1:1-17. He highlights how the lineage of Jesus was traced back

5 of 197

Matthew 1:18 - 1:25

Gospel of Matthew

In this discussion, Steve Gregg explores the end portion of Matthew chapter 1, beginning with the genealogy of Joseph, Jesus' legal father. Joseph's r

2 of 197

Matthew Introduction (Part 2)

Gospel of Matthew

Steve Gregg discusses the importance of acknowledging the truth of the Gospels and the life of Jesus, despite potential doubts and skepticism. He ackn

Series by Steve Gregg

Gospel of John

In this 38-part series, Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the Gospel of John, providing insightful analysis and exploring important themes su

Daniel

Steve Gregg discusses various parts of the book of Daniel, exploring themes of prophecy, historical accuracy, and the significance of certain events.

Genuinely Following Jesus

Steve Gregg's lecture series on discipleship emphasizes the importance of following Jesus and becoming more like Him in character and values. He highl

1 Timothy

In this 8-part series, Steve Gregg provides in-depth teachings, insights, and practical advice on the book of 1 Timothy, covering topics such as the r

What Are We to Make of Israel

Steve Gregg explores the intricate implications of certain biblical passages in relation to the future of Israel, highlighting the historical context,

Micah

Steve Gregg provides a verse-by-verse analysis and teaching on the book of Micah, exploring the prophet's prophecies of God's judgment, the birthplace

2 Thessalonians

A thought-provoking biblical analysis by Steve Gregg on 2 Thessalonians, exploring topics such as the concept of rapture, martyrdom in church history,

Gospel of Mark

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the Gospel of Mark.

The Narrow Path is the radio and internet ministry of Steve Gregg, a servant Bible tea

Gospel of Luke

In this 32-part series, Steve Gregg provides in-depth commentary and historical context on each chapter of the Gospel of Luke, shedding new light on i

Exodus

Steve Gregg's "Exodus" is a 25-part teaching series that delves into the book of Exodus verse by verse, covering topics such as the Ten Commandments,

More on OpenTheo

Is It a Sin to Feel Let Down by God?

#STRask

November 6, 2025

Questions about whether it’s a sin to feel let down by God and whether it would be easier to have a personal relationship with a rock than with a God

How Can I Improve My Informal Writing?

#STRask

October 6, 2025

Question about how you can improve your informal writing (e.g., blog posts) when you don’t have access to an editor.

* Do you have any thoughts or

Is It Possible There’s a Being That’s Greater Than God?

#STRask

February 5, 2026

Questions about whether it’s possible there’s a being that’s greater than God and that’s outside of God’s comprehension and omniscience, and how to ex

Does God Really Need a “Pound of Flesh” to Forgive Sins?

#STRask

January 12, 2026

Questions about how to answer the challenge that God doesn’t need a “pound of flesh” to forgive sins but can simply forgive, and whether the claim in

What Tools of Reasoning Help You Know What’s True, Right, and Good?

#STRask

December 4, 2025

Question about what tools of reasoning help us determine whether something is true or false, right or wrong, good or bad before bringing Scripture int

The Heidelberg Catechism with R. Scott Clark

Life and Books and Everything

November 3, 2025

You may not think you need 1,000 pages on the Heidelberg Catechism, but you do! R. Scott Clark, professor at Westminster Seminary California, has writ

The Golden Thread of the Western Tradition with Allen Guelzo

Life and Books and Everything

October 6, 2025

Dr. Guelzo is back once again for another record setting appearance on LBE. Although he just moved across the country, Allen still made time to talk t

Why Should We Pray If God Already Knows What’s Going to Happen?

#STRask

January 29, 2026

Questions about why we should pray if God already knows what’s going to happen, how the effectiveness of prayer is measured, and whether or not things

How Do We Advocate for Christian Policy Without Making the Government Interfere in Every Area of Life?

#STRask

November 20, 2025

Questions about how to advocate for Christian policy without making the government interfere in every area of life, and the differences between the mo

What About Those Who Never Heard the Name of Jesus?

#STRask

December 22, 2025

Questions about what will happen to those who never heard of Jesus or were brought up in a different faith, whether there’s biblical warrant to think

What Are Some Good Ways to Start a Conversation About God with Family Members?

#STRask

October 30, 2025

Questions about how to start a conversation about God with non-Christian family members, how to keep from becoming emotional when discussing faith iss

Why Do We Say Someone Was Saved on a Particular Date If It Was Part of an Eternal Plan?

#STRask

November 24, 2025

Questions about why we say someone was saved on a particular date if it was part of an eternal plan, the Roman Catholic view of the gospel vs. the Bib

Life and Ministry in Charlotte and in the SBC with Clint Pressley

Life and Books and Everything

December 15, 2025

In a rare cultural anomaly that may never be repeated in our lifetimes, the current SBC President and current PCA Moderator live in the same neighborh

Could the Writers of Scripture Have Been Influenced by Their Fallen Nature?

#STRask

October 23, 2025

Questions about whether or not it’s reasonable to worry that some of our current doctrines were influenced by the fallen nature of the apostles, and h

Did God Create Us So He Wouldn’t Be Alone?

#STRask

November 3, 2025

Questions about whether God created us so he wouldn’t be alone, what he had before us, and a comparison between the Muslim view of God and the Christi