The Good Samaritan (Part 2)

The Life and Teachings of Christ — Steve GreggNext in this series

Fear of Man and Fear of God (Part 1)

The Good Samaritan (Part 2)

The Life and Teachings of ChristSteve Gregg

In this talk, Steve Gregg discusses the parable of the Good Samaritan and its implications for acts of compassion in everyday life. He reflects on the notion of chance and the role of individual agency when it comes to helping others, using the example of a priest who failed to aid a wounded man on the road. Gregg emphasizes the significance of demonstrating kindness and love to all people, regardless of their background or beliefs, as a reflection of God's goodness and a call to repentance.

More from The Life and Teachings of Christ

119 of 180

Next in this series

Fear of Man and Fear of God (Part 1)

The Life and Teachings of Christ

In this talk, Steve Gregg discusses the importance of prioritizing listening to God over serving Him. He uses the story of Mary and Martha to illustra

120 of 180

Fear of Man and Fear of God (Part 2)

The Life and Teachings of Christ

In this talk, Steve Gregg discusses the fear of man versus the fear of God. He points out that fearing man over God can harm one eternally, while fear

117 of 180

The Good Samaritan (Part 1)

The Life and Teachings of Christ

Steve Gregg explores the well-known parable of the Good Samaritan in Luke 10, highlighting the importance of measuring true goodness and the standard

Series by Steve Gregg

1 John

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the book of 1 John, providing commentary and insights on topics such as walking in the light and love of Go

Jonah

Steve Gregg's lecture on the book of Jonah focuses on the historical context of Nineveh, where Jonah was sent to prophesy repentance. He emphasizes th

Sermon on the Mount

Steve Gregg's 14-part series on the Sermon on the Mount deepens the listener's understanding of the Beatitudes and other teachings in Matthew 5-7, emp

Beyond End Times

In "Beyond End Times", Steve Gregg discusses the return of Christ, judgement and rewards, and the eternal state of the saved and the lost.

What Are We to Make of Israel

Steve Gregg explores the intricate implications of certain biblical passages in relation to the future of Israel, highlighting the historical context,

1 Timothy

In this 8-part series, Steve Gregg provides in-depth teachings, insights, and practical advice on the book of 1 Timothy, covering topics such as the r

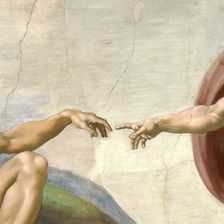

Creation and Evolution

In the series "Creation and Evolution" by Steve Gregg, the evidence against the theory of evolution is examined, questioning the scientific foundation

The Holy Spirit

Steve Gregg's series "The Holy Spirit" explores the concept of the Holy Spirit and its implications for the Christian life, emphasizing genuine spirit

2 Timothy

In this insightful series on 2 Timothy, Steve Gregg explores the importance of self-control, faith, and sound doctrine in the Christian life, urging b

Philippians

In this 2-part series, Steve Gregg explores the book of Philippians, encouraging listeners to find true righteousness in Christ rather than relying on

More on OpenTheo

Can You Provide Verifiable, Non-Religious Evidence That a Supernatural Jesus Existed?

#STRask

November 10, 2025

Question about providing verifiable, non-religious evidence that a supernatural Jesus existed.

* I am an atheist and militantly anti-god-belief. Ho

The Man on the Middle Cross with Alistair Begg

Life and Books and Everything

November 10, 2025

If you haven’t seen the viral clip, go see it right now. In this episode, Kevin talks to Alistair about the preaching clip he didn’t intend to give, h

Keri Ingraham: School Choice and Education Reform

Knight & Rose Show

January 24, 2026

Wintery Knight and guest host Bonnie welcome Dr. Keri Ingraham to discuss school choice and education reform. They discuss the public school monopoly'

Why Are So Many Christians Condemning LGB People Just Because of How They Love?

#STRask

January 15, 2026

Questions about Christians condemning LGB people just because of how they love, how God can expect someone to be celibate when others are free to marr

Shouldn’t I Be Praying for My Soul Rather Than for Material Things?

#STRask

February 2, 2026

Questions about whether we should be praying for our souls rather than for material things, why we need to pray about decisions, whether the devil can

How Can We Know Who Is Teaching the Same Gospel Paul Taught?

#STRask

February 16, 2026

Questions about how we can know who is teaching the same gospel Paul taught, and whether or not Jeremiah 1:5 supports the idea that we pre-existed in

Why Would Any Rational Person Have to Use Any Religious Book?

#STRask

December 8, 2025

Questions about why any rational person would have to use any religious book, whether apologetics would be redundant if there were actually a good, un

Christmas Cranks and Christmas Blessings with Justin Taylor and Collin Hansen

Life and Books and Everything

December 17, 2025

If you are looking for a podcast where three friends talk about whatever they want to talk about and ramble on about sports, books, and grievances, th

E. Calvin Beisner: Climate and Energy Policy

Knight & Rose Show

January 4, 2026

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose welcome Dr. E. Calvin Beisner to discuss climate and energy policy. They explore Biblical dominion and stewardship, con

How Do I Determine Which Topics at Work Are Worth Commenting On?

#STRask

January 5, 2026

Questions about how to determine which topics at work are worth commenting on, and a good way to respond when you’re in a group Bible study and hear e

An Invitation to the 2026 Coram Deo Pastors Conference

Life and Books and Everything

February 18, 2026

"I love being a pastor, and I love pastors, which is why I hope you will consider joining us at the Coram Deo Pastors Conference in 2026." —Kevin DeYo

How Do We Advocate for Christian Policy Without Making the Government Interfere in Every Area of Life?

#STRask

November 20, 2025

Questions about how to advocate for Christian policy without making the government interfere in every area of life, and the differences between the mo

Does Open-Mindedness Require Studying Other Religions Before Becoming a Christian?

#STRask

February 9, 2026

Questions about the claim that if Christians really want to be open-minded, they need to read and study other religions before committing to Christian

Conservatism and Religious Freedom with John Wilsey

Life and Books and Everything

October 27, 2025

What is conservatism? And why does it go hand in hand with religious freedom? How should we think about the American experiment of ordered liberty? Ha

How Do You Justify Calling Jesus the Messiah?

#STRask

December 18, 2025

Questions about how one can justify calling Jesus the Messiah when he didn’t fulfill the Hebrew messianic prophecies, and whether the reason for the v