Zechariah Introduction

ZechariahSteve Gregg

Zechariah is one of the most difficult books in the Bible, but Steve Gregg offers a comprehensive introduction to the book. He explains how Zechariah is organized and touches on its four letters and the challenges with its pronunciation. Gregg also discusses the historical context of the book, its relevance to Christianity, and explains that the book is divided into two main sections. Overall, Gregg provides a useful guide for anyone seeking to further understand this complicated book of the Bible.

More from Zechariah

2 of 10

Next in this series

Zechariah 1 - 2

Zechariah

This section of Zechariah is full of rapid, abrupt visions that can be difficult to comprehend without careful attention. However, Steve Gregg suggest

3 of 10

Zechariah 3 - 4

Zechariah

This lecture by Steve Gregg provides insights on the spiritual meanings and symbolism within the books of Zechariah and Exodus. Gregg delves into the

Series by Steve Gregg

Esther

In this two-part series, Steve Gregg teaches through the book of Esther, discussing its historical significance and the story of Queen Esther's braver

Genuinely Following Jesus

Steve Gregg's lecture series on discipleship emphasizes the importance of following Jesus and becoming more like Him in character and values. He highl

Ten Commandments

Steve Gregg delivers a thought-provoking and insightful lecture series on the relevance and importance of the Ten Commandments in modern times, delvin

Gospel of Mark

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the Gospel of Mark.

The Narrow Path is the radio and internet ministry of Steve Gregg, a servant Bible tea

Habakkuk

In his series "Habakkuk," Steve Gregg delves into the biblical book of Habakkuk, addressing the prophet's questions about God's actions during a troub

2 Kings

In this 12-part series, Steve Gregg provides a thorough verse-by-verse analysis of the biblical book 2 Kings, exploring themes of repentance, reform,

Ecclesiastes

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the book of Ecclesiastes, exploring its themes of mortality, the emptiness of worldly pursuits, and the imp

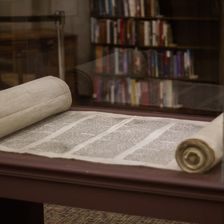

The Jewish Roots Movement

"The Jewish Roots Movement" by Steve Gregg is a six-part series that explores Paul's perspective on Torah observance, the distinction between Jewish a

Hebrews

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the book of Hebrews, focusing on themes, warnings, the new covenant, judgment, faith, Jesus' authority, and

Individual Topics

This is a series of over 100 lectures by Steve Gregg on various topics, including idolatry, friendships, truth, persecution, astrology, Bible study,

More on OpenTheo

What Is Wrong with Wokeness? With Neil Shenvi

Life and Books and Everything

January 19, 2026

In this timely interview, Kevin talks to Neil Shenvi about his new book (co-authored with Pat Sawyer), entitled “Post Woke: Asserting a Biblical Visio

Are You Accursed If You Tithe?

#STRask

December 15, 2025

Questions about whether anyone who tithes is not a Christian and is accursed since Paul says that if you obey one part of the Mosaic Law you’re obliga

Lora Ries: Border Security and Immigration Policy

Knight & Rose Show

December 7, 2025

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose welcome Lora Ries to discuss border security and immigration policy. They explore Biden's policy changes, like ending R

Does Open-Mindedness Require Studying Other Religions Before Becoming a Christian?

#STRask

February 9, 2026

Questions about the claim that if Christians really want to be open-minded, they need to read and study other religions before committing to Christian

Prove to Me That Jesus Is Not a Created Being

#STRask

January 26, 2026

Questions about why we should think Jesus is not a created being, and what it means to say God became fully human if part of being human means not bei

Could the Writers of Scripture Have Been Influenced by Their Fallen Nature?

#STRask

October 23, 2025

Questions about whether or not it’s reasonable to worry that some of our current doctrines were influenced by the fallen nature of the apostles, and h

Kingdom Priorities: Following the Teachings of Jesus

Knight & Rose Show

February 14, 2026

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose discuss Jesus' teachings from the Gospels, emphasizing truth, evidence, self-denial, and forgiveness. They explore pass

Conservatism and Religious Freedom with John Wilsey

Life and Books and Everything

October 27, 2025

What is conservatism? And why does it go hand in hand with religious freedom? How should we think about the American experiment of ordered liberty? Ha

Why Do We Say Someone Was Saved on a Particular Date If It Was Part of an Eternal Plan?

#STRask

November 24, 2025

Questions about why we say someone was saved on a particular date if it was part of an eternal plan, the Roman Catholic view of the gospel vs. the Bib

The Resurrection Standoff: Licona vs. Ehrman on the Unbelievable Podcast

Risen Jesus

October 22, 2025

This episode is taken from the Unbelievable podcast with Justin Brierly in 2011 when Dr. Bart Ehrman and Dr. Michael Licona address the question: Is t

Why Are So Many Christians Condemning LGB People Just Because of How They Love?

#STRask

January 15, 2026

Questions about Christians condemning LGB people just because of how they love, how God can expect someone to be celibate when others are free to marr

Is It a Sin to Feel Let Down by God?

#STRask

November 6, 2025

Questions about whether it’s a sin to feel let down by God and whether it would be easier to have a personal relationship with a rock than with a God

Does God Really Need a “Pound of Flesh” to Forgive Sins?

#STRask

January 12, 2026

Questions about how to answer the challenge that God doesn’t need a “pound of flesh” to forgive sins but can simply forgive, and whether the claim in

How Would You Convince Someone That Evil Exists?

#STRask

November 17, 2025

Questions about how to convince someone that evil exists, whether Charlie Kirk’s murder was part of God’s plan, whether that would mean the murderer d

The Making of the American Mind with Matthew Spalding

Life and Books and Everything

February 2, 2026

The United States is unique in how much attention it pays to its founding, its founders, and its founding documents. Arguably, the most famous and mos