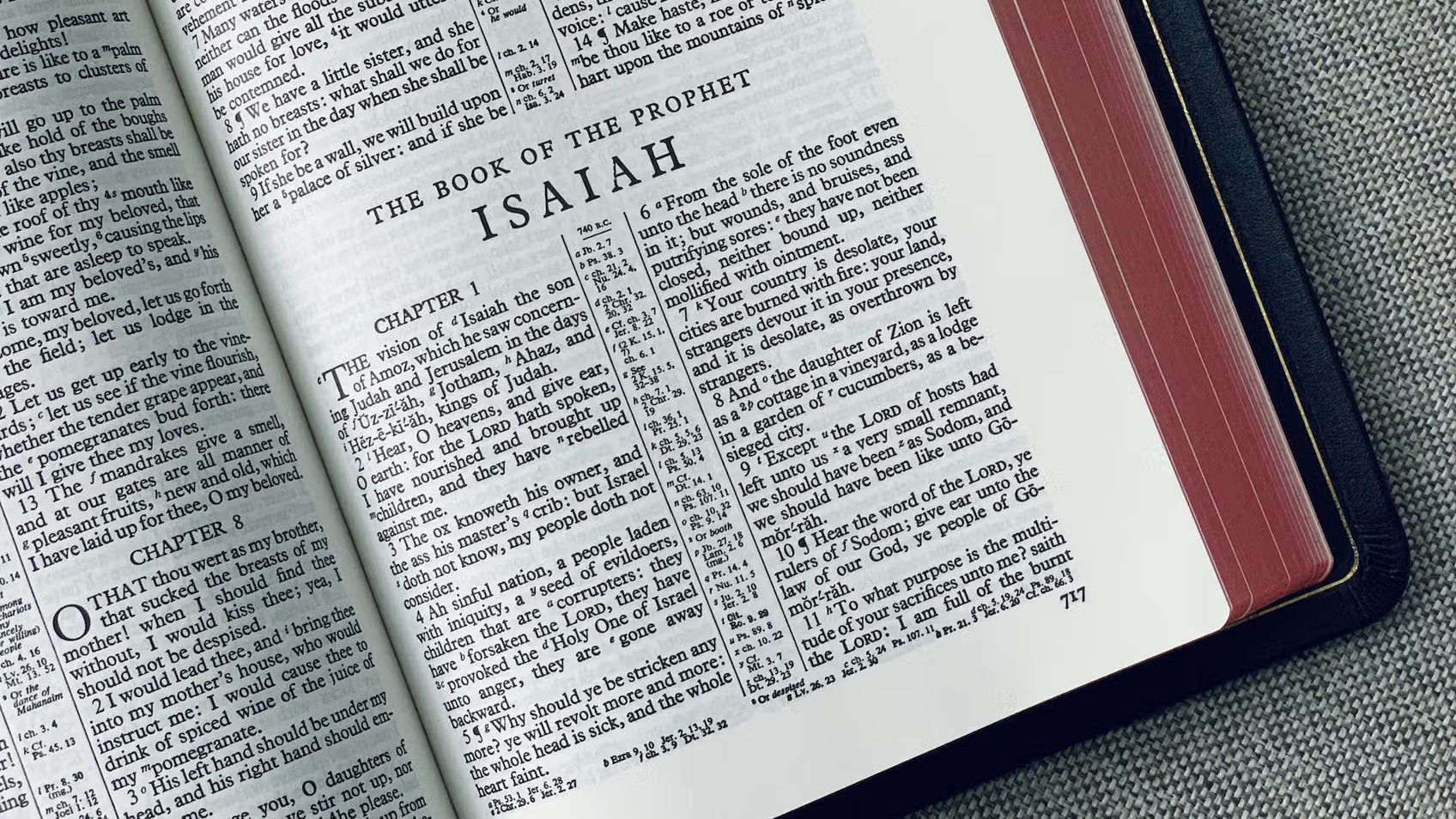

Introduction to Isaiah

Isaiah: A Topical Look At IsaiahSteve Gregg

In this introduction to the biblical book of Isaiah, Steve Gregg provides an overview of the prophet's unique position in Israelite history and some of the major themes and sections of his writings. Gregg notes that while some scholars debate the authorship and structure of the book, its message of judgment and comfort has resonated with readers and believers for centuries. While encouraging listeners to read along with assigned passages, Gregg also highlights some of the key themes and ideas that recur throughout Isaiah, including the promise of a Messianic Age and the importance of trusting in God's ultimate plan.

More from Isaiah: A Topical Look At Isaiah

2 of 15

Next in this series

Rapid Survey of Isaiah 1 - 23

Isaiah: A Topical Look At Isaiah

In this rapid survey, Steve Gregg explores the first 23 chapters of Isaiah, focusing on key themes and prophecies. He emphasizes that God's correction

3 of 15

Rapid Survey of Isaiah 24 - 66

Isaiah: A Topical Look At Isaiah

In this discussion, Steve Gregg surveys passages from Isaiah 24 to 66. He notes that while some interpret biblical prophecies of the earth's destructi

Series by Steve Gregg

Joel

Steve Gregg provides a thought-provoking analysis of the book of Joel, exploring themes of judgment, restoration, and the role of the Holy Spirit.

2 Corinthians

This series by Steve Gregg is a verse-by-verse study through 2 Corinthians, covering various themes such as new creation, justification, comfort durin

Survey of the Life of Christ

Steve Gregg's 9-part series explores various aspects of Jesus' life and teachings, including his genealogy, ministry, opposition, popularity, pre-exis

Daniel

Steve Gregg discusses various parts of the book of Daniel, exploring themes of prophecy, historical accuracy, and the significance of certain events.

What You Absolutely Need To Know Before You Get Married

Steve Gregg's lecture series on marriage emphasizes the gravity of the covenant between two individuals and the importance of understanding God's defi

Cultivating Christian Character

Steve Gregg's lecture series focuses on cultivating holiness and Christian character, emphasizing the need to have God's character and to walk in the

Philippians

In this 2-part series, Steve Gregg explores the book of Philippians, encouraging listeners to find true righteousness in Christ rather than relying on

Deuteronomy

Steve Gregg provides a comprehensive and insightful commentary on the book of Deuteronomy, discussing the Israelites' relationship with God, the impor

Judges

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the Book of Judges in this 16-part series, exploring its historical and cultural context and highlighting t

Malachi

Steve Gregg's in-depth exploration of the book of Malachi provides insight into why the Israelites were not prospering, discusses God's election, and

More on OpenTheo

Can Two Logical People Come to Conflicting Conclusions Without Committing a Fallacy?

#STRask

January 8, 2026

Questions about whether two logical people can come to conflicting conclusions on a topic without committing a fallacy, how Greg, as a public figure,

An Invitation to the 2026 Coram Deo Pastors Conference

Life and Books and Everything

February 18, 2026

"I love being a pastor, and I love pastors, which is why I hope you will consider joining us at the Coram Deo Pastors Conference in 2026." —Kevin DeYo

How Do We Advocate for Christian Policy Without Making the Government Interfere in Every Area of Life?

#STRask

November 20, 2025

Questions about how to advocate for Christian policy without making the government interfere in every area of life, and the differences between the mo

Could the Writers of Scripture Have Been Influenced by Their Fallen Nature?

#STRask

October 23, 2025

Questions about whether or not it’s reasonable to worry that some of our current doctrines were influenced by the fallen nature of the apostles, and h

Why Do We Say Someone Was Saved on a Particular Date If It Was Part of an Eternal Plan?

#STRask

November 24, 2025

Questions about why we say someone was saved on a particular date if it was part of an eternal plan, the Roman Catholic view of the gospel vs. the Bib

Is It Possible There’s a Being That’s Greater Than God?

#STRask

February 5, 2026

Questions about whether it’s possible there’s a being that’s greater than God and that’s outside of God’s comprehension and omniscience, and how to ex

What Are Some Good Ways to Start a Conversation About God with Family Members?

#STRask

October 30, 2025

Questions about how to start a conversation about God with non-Christian family members, how to keep from becoming emotional when discussing faith iss

How Can I Explain Modesty to My Daughter?

#STRask

November 27, 2025

Questions about how to explain modesty to a nine-year-old in a way that won’t cause shame about her body, and when and how to tell a child about a pre

Are Demon Possessions and Exorcisms in the New Testament Literal?

#STRask

December 11, 2025

Questions about whether references to demon possessions and exorcisms in the New Testament are literal, how to talk to young children about ghosts, an

The Making of the American Mind with Matthew Spalding

Life and Books and Everything

February 2, 2026

The United States is unique in how much attention it pays to its founding, its founders, and its founding documents. Arguably, the most famous and mos

Sense, Sensibility, and Adam Smith with Jan Van Vliet

Life and Books and Everything

February 16, 2026

This year is a special anniversary for the United States as Americans celebrate 250 years of independence. But 1776 was an important year in more ways

What Do You Think About Churches Advertising on Social Media?

#STRask

January 19, 2026

Questions about whether there’s an issue with churches advertising on social media, whether it’s weird if we pray along with a YouTuber, and whether C

Does God Really Need a “Pound of Flesh” to Forgive Sins?

#STRask

January 12, 2026

Questions about how to answer the challenge that God doesn’t need a “pound of flesh” to forgive sins but can simply forgive, and whether the claim in

How Can We Know Who Is Teaching the Same Gospel Paul Taught?

#STRask

February 16, 2026

Questions about how we can know who is teaching the same gospel Paul taught, and whether or not Jeremiah 1:5 supports the idea that we pre-existed in

Is It a Sin to Feel Let Down by God?

#STRask

November 6, 2025

Questions about whether it’s a sin to feel let down by God and whether it would be easier to have a personal relationship with a rock than with a God