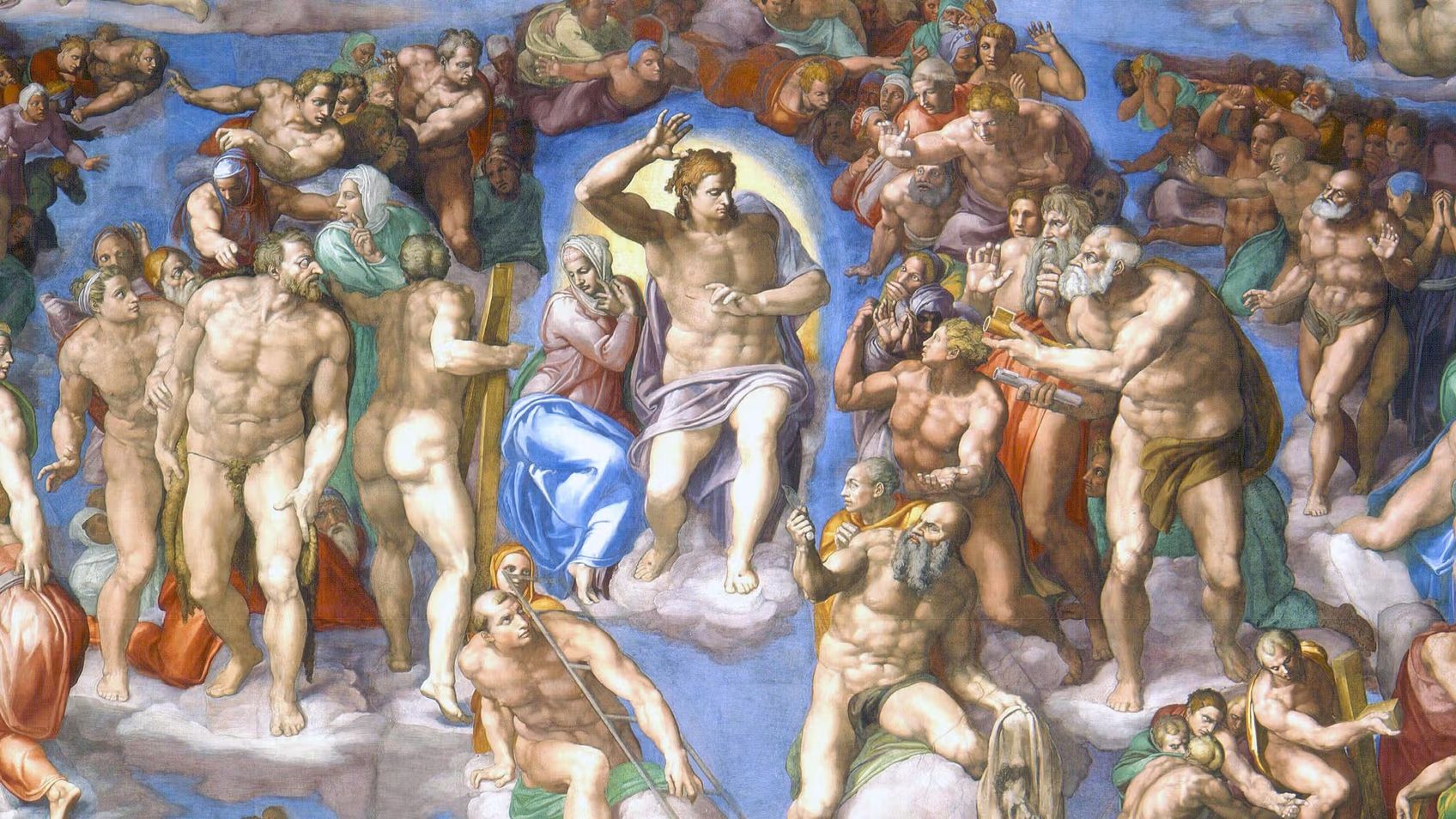

Final State of Unbelievers

Beyond End TimesSteve Gregg

Steve Gregg discusses the concept of the final state of unbelievers, which refers to what happens to non-believers after they die. He explores the idea of annihilationism and its association with certain religious groups like Jehovah's Witnesses and Seventh-day Adventists. While annihilationism was often considered a heretical belief for evangelicals, Gregg has spent the past 15 years researching and considering it as he re-examines the traditional view. He delves into the different scriptural arguments both for and against the idea of the final state of unbelievers.

More from Beyond End Times

3 of 4

The Eternal State of the Saved

Beyond End Times

In this talk, Steve Gregg discusses the eternal state of the saved based on his interpretation of scripture. He asserts that the eternity of heaven is

Series by Steve Gregg

Galatians

In this six-part series, Steve Gregg provides verse-by-verse commentary on the book of Galatians, discussing topics such as true obedience, faith vers

Making Sense Out Of Suffering

In "Making Sense Out Of Suffering," Steve Gregg delves into the philosophical question of why a good sovereign God allows suffering in the world.

Ecclesiastes

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the book of Ecclesiastes, exploring its themes of mortality, the emptiness of worldly pursuits, and the imp

Creation and Evolution

In the series "Creation and Evolution" by Steve Gregg, the evidence against the theory of evolution is examined, questioning the scientific foundation

How Can I Know That I Am Really Saved?

In this four-part series, Steve Gregg explores the concept of salvation using 1 John as a template and emphasizes the importance of love, faith, godli

Ezekiel

Discover the profound messages of the biblical book of Ezekiel as Steve Gregg provides insightful interpretations and analysis on its themes, propheti

Revelation

In this 19-part series, Steve Gregg offers a verse-by-verse analysis of the book of Revelation, discussing topics such as heavenly worship, the renewa

Word of Faith

"Word of Faith" by Steve Gregg is a four-part series that provides a detailed analysis and thought-provoking critique of the Word Faith movement's tea

Knowing God

Knowing God by Steve Gregg is a 16-part series that delves into the dynamics of relationships with God, exploring the importance of walking with Him,

2 Corinthians

This series by Steve Gregg is a verse-by-verse study through 2 Corinthians, covering various themes such as new creation, justification, comfort durin

More on OpenTheo

The Making of the American Mind with Matthew Spalding

Life and Books and Everything

February 2, 2026

The United States is unique in how much attention it pays to its founding, its founders, and its founding documents. Arguably, the most famous and mos

Why Should We Pray If God Already Knows What’s Going to Happen?

#STRask

January 29, 2026

Questions about why we should pray if God already knows what’s going to happen, how the effectiveness of prayer is measured, and whether or not things

E. Calvin Beisner: Climate and Energy Policy

Knight & Rose Show

January 4, 2026

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose welcome Dr. E. Calvin Beisner to discuss climate and energy policy. They explore Biblical dominion and stewardship, con

Why Does the Bible Teach You How to Be a Proper Slave Owner?

#STRask

November 13, 2025

Question about why it seems like the Bible teaches you how to be a proper slave owner rather than than saying, “Stop it. Give them freedom.”

* It s

The Resurrection Standoff: Licona vs. Ehrman on the Unbelievable Podcast

Risen Jesus

October 22, 2025

This episode is taken from the Unbelievable podcast with Justin Brierly in 2011 when Dr. Bart Ehrman and Dr. Michael Licona address the question: Is t

Prove to Me That Jesus Is Not a Created Being

#STRask

January 26, 2026

Questions about why we should think Jesus is not a created being, and what it means to say God became fully human if part of being human means not bei

What Do You Think About Churches Advertising on Social Media?

#STRask

January 19, 2026

Questions about whether there’s an issue with churches advertising on social media, whether it’s weird if we pray along with a YouTuber, and whether C

Protestants and Catholics: What’s the Difference? With Chad Van Dixhoorn, Blair Smith, and Mark McDowell

Life and Books and Everything

November 26, 2025

How should Protestants think about the Catholic Mass? About the Eucharist? About the history and development of the papacy? In this panel discussion,

How Would You Convince Someone That Evil Exists?

#STRask

November 17, 2025

Questions about how to convince someone that evil exists, whether Charlie Kirk’s murder was part of God’s plan, whether that would mean the murderer d

What Is Wrong with Wokeness? With Neil Shenvi

Life and Books and Everything

January 19, 2026

In this timely interview, Kevin talks to Neil Shenvi about his new book (co-authored with Pat Sawyer), entitled “Post Woke: Asserting a Biblical Visio

Did God Create Us So He Wouldn’t Be Alone?

#STRask

November 3, 2025

Questions about whether God created us so he wouldn’t be alone, what he had before us, and a comparison between the Muslim view of God and the Christi

Are Demon Possessions and Exorcisms in the New Testament Literal?

#STRask

December 11, 2025

Questions about whether references to demon possessions and exorcisms in the New Testament are literal, how to talk to young children about ghosts, an

Lora Ries: Border Security and Immigration Policy

Knight & Rose Show

December 7, 2025

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose welcome Lora Ries to discuss border security and immigration policy. They explore Biden's policy changes, like ending R

How Can We Know Who Is Teaching the Same Gospel Paul Taught?

#STRask

February 16, 2026

Questions about how we can know who is teaching the same gospel Paul taught, and whether or not Jeremiah 1:5 supports the idea that we pre-existed in

Sense, Sensibility, and Adam Smith with Jan Van Vliet

Life and Books and Everything

February 16, 2026

This year is a special anniversary for the United States as Americans celebrate 250 years of independence. But 1776 was an important year in more ways