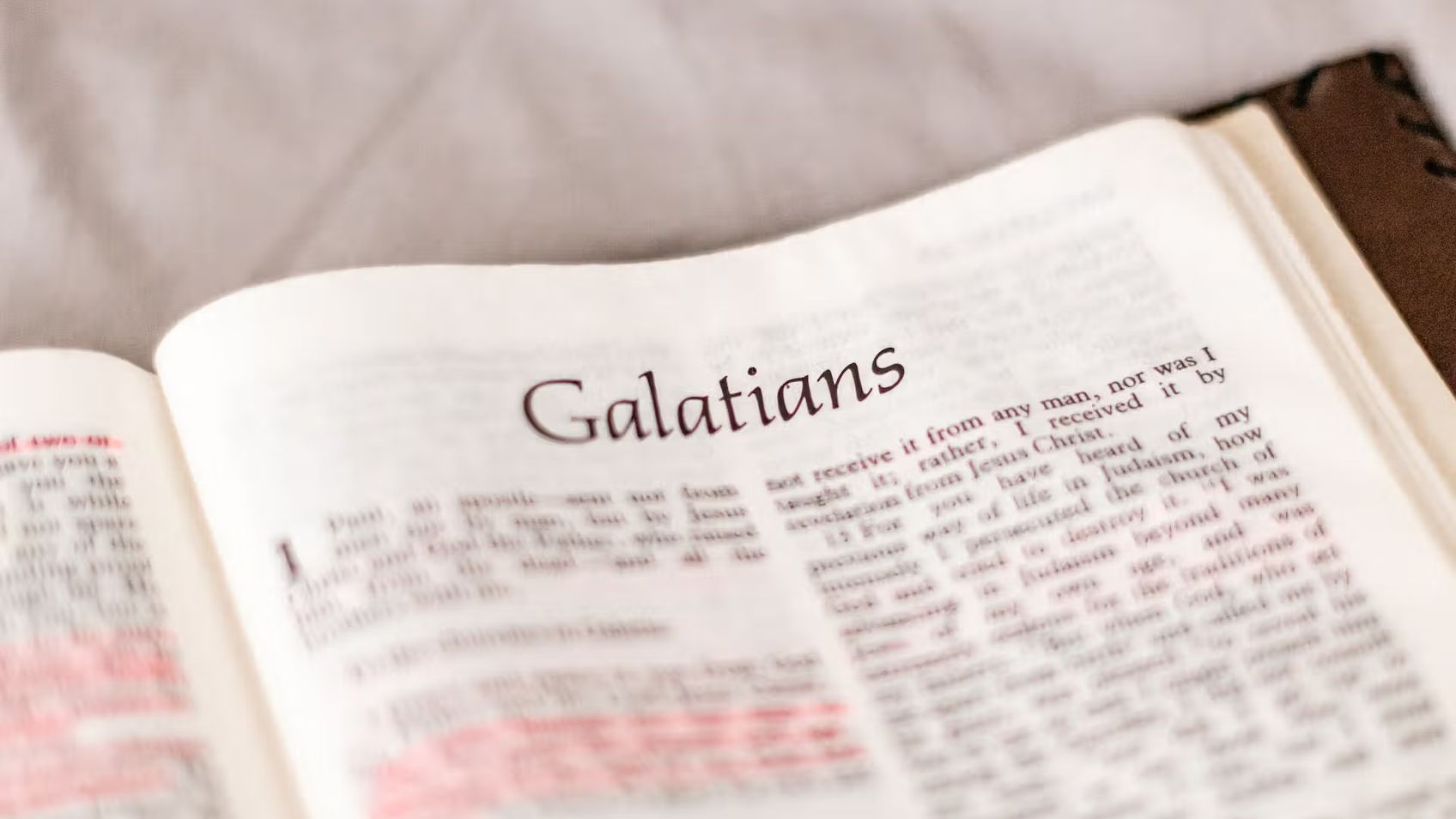

Galatians Introduction, 1:1 - 1:10

GalatiansSteve Gregg

In this commentary on Galatians, Steve Gregg offers insights into the context and timeline of Paul's writing. He discusses Paul's qualifications as an apostle and his relationship with the other apostles, as well as the controversy surrounding circumcision and the requirements for salvation. He suggests that internal evidence points to an early date for the writing of Galatians, before the Jerusalem Council, and highlights Paul's powerful arguments against circumcision and the "weak beggarly elements" of the world. Throughout his commentary, Gregg offers a nuanced understanding of Paul's theology and teachings.

More from Galatians

2 of 6

Next in this series

Galatians 1:11 - 2:21

Galatians

In this Biblical text, Steve Gregg examines Galatians 1:11 - 2:21 to explore the charge that the Apostle Paul modified his behavior and message to ple

3 of 6

Galatians 3:1 - 3:18

Galatians

In this commentary on Galatians 3:1-18, Steve Gregg discusses the idea that true obedience to God comes from a heart filled with love and gratitude, r

Series by Steve Gregg

Galatians

In this six-part series, Steve Gregg provides verse-by-verse commentary on the book of Galatians, discussing topics such as true obedience, faith vers

Titus

In this four-part series from Steve Gregg, listeners are taken on an insightful journey through the book of Titus, exploring issues such as good works

Original Sin & Depravity

In this two-part series by Steve Gregg, he explores the theological concepts of Original Sin and Human Depravity, delving into different perspectives

Psalms

In this 32-part series, Steve Gregg provides an in-depth verse-by-verse analysis of various Psalms, highlighting their themes, historical context, and

What Are We to Make of Israel

Steve Gregg explores the intricate implications of certain biblical passages in relation to the future of Israel, highlighting the historical context,

Zephaniah

Experience the prophetic words of Zephaniah, written in 612 B.C., as Steve Gregg vividly brings to life the impending judgement, destruction, and hope

1 Timothy

In this 8-part series, Steve Gregg provides in-depth teachings, insights, and practical advice on the book of 1 Timothy, covering topics such as the r

Philippians

In this 2-part series, Steve Gregg explores the book of Philippians, encouraging listeners to find true righteousness in Christ rather than relying on

Jude

Steve Gregg provides a comprehensive analysis of the biblical book of Jude, exploring its themes of faith, perseverance, and the use of apocryphal lit

The Beatitudes

Steve Gregg teaches through the Beatitudes in Jesus' Sermon on the Mount.

More on OpenTheo

Why Are So Many Christians Condemning LGB People Just Because of How They Love?

#STRask

January 15, 2026

Questions about Christians condemning LGB people just because of how they love, how God can expect someone to be celibate when others are free to marr

How Do I Determine Which Topics at Work Are Worth Commenting On?

#STRask

January 5, 2026

Questions about how to determine which topics at work are worth commenting on, and a good way to respond when you’re in a group Bible study and hear e

Kingdom Priorities: Following the Teachings of Jesus

Knight & Rose Show

February 14, 2026

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose discuss Jesus' teachings from the Gospels, emphasizing truth, evidence, self-denial, and forgiveness. They explore pass

What Is Wrong with Wokeness? With Neil Shenvi

Life and Books and Everything

January 19, 2026

In this timely interview, Kevin talks to Neil Shenvi about his new book (co-authored with Pat Sawyer), entitled “Post Woke: Asserting a Biblical Visio

How Can I Explain Modesty to My Daughter?

#STRask

November 27, 2025

Questions about how to explain modesty to a nine-year-old in a way that won’t cause shame about her body, and when and how to tell a child about a pre

Protestants and Catholics: What’s the Difference? With Chad Van Dixhoorn, Blair Smith, and Mark McDowell

Life and Books and Everything

November 26, 2025

How should Protestants think about the Catholic Mass? About the Eucharist? About the history and development of the papacy? In this panel discussion,

An Invitation to the 2026 Coram Deo Pastors Conference

Life and Books and Everything

February 18, 2026

"I love being a pastor, and I love pastors, which is why I hope you will consider joining us at the Coram Deo Pastors Conference in 2026." —Kevin DeYo

Is Greg Placing His Faith in the Wrong Thing?

#STRask

February 12, 2026

Questions about Greg placing his faith in his personal assessment of which truth claims best match reality rather than in the revelation of God in Jes

How Do We Advocate for Christian Policy Without Making the Government Interfere in Every Area of Life?

#STRask

November 20, 2025

Questions about how to advocate for Christian policy without making the government interfere in every area of life, and the differences between the mo

The Making of the American Mind with Matthew Spalding

Life and Books and Everything

February 2, 2026

The United States is unique in how much attention it pays to its founding, its founders, and its founding documents. Arguably, the most famous and mos

How Can We Know Who Is Teaching the Same Gospel Paul Taught?

#STRask

February 16, 2026

Questions about how we can know who is teaching the same gospel Paul taught, and whether or not Jeremiah 1:5 supports the idea that we pre-existed in

Did Jesus Prove He Wasn’t Sinless When He Overturned the Tables?

#STRask

December 29, 2025

Questions about whether Jesus proved he wasn’t sinless when he overturned the tables, whether Jesus’ response to the Pharisees in Mark 3:22–26 was a b

Why Would Any Rational Person Have to Use Any Religious Book?

#STRask

December 8, 2025

Questions about why any rational person would have to use any religious book, whether apologetics would be redundant if there were actually a good, un

Is It Possible There’s a Being That’s Greater Than God?

#STRask

February 5, 2026

Questions about whether it’s possible there’s a being that’s greater than God and that’s outside of God’s comprehension and omniscience, and how to ex

The Heidelberg Catechism with R. Scott Clark

Life and Books and Everything

November 3, 2025

You may not think you need 1,000 pages on the Heidelberg Catechism, but you do! R. Scott Clark, professor at Westminster Seminary California, has writ