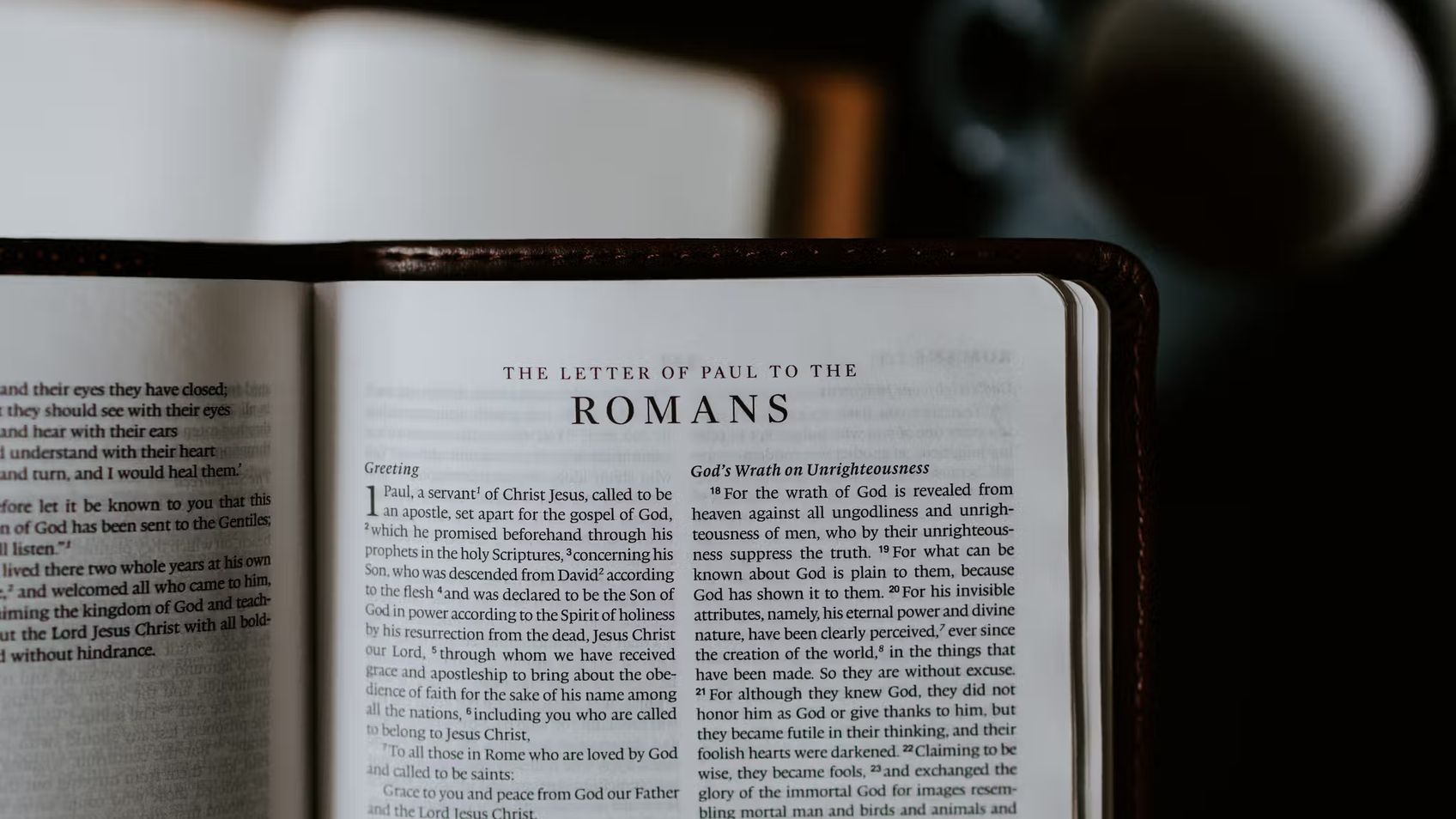

Romans 1 (Part 2)

RomansSteve Gregg

In this discussion, Steve Gregg offers insights into the second part of Romans 1, exploring the meaning of phrases and words in their historical and biblical context. He highlights the power of the Gospel message, which reveals the righteousness of God that is obtained through faith in Jesus Christ. Gregg also emphasizes the concept of faithfulness as a covenantal relationship between God and believers, where both parties are expected to fulfill their obligations, rather than equating it with perfect performance or earning salvation through works. Ultimately, he encourages his audience to critically examine traditional and denominational beliefs in light of biblical truth.

More from Romans

6 of 29

Next in this series

Romans 1 (Part 3)

Romans

Steve Gregg explores the message and context of Romans 1 in a thought-provoking discussion. He notes that the overarching theme of Romans 1:16-17 is t

7 of 29

Romans 2:1 - 2:10

Romans

The second chapter of Romans continues the previous chapter's description of a sinful society, establishing universal guilt for both Jews and Gentiles

4 of 29

Romans 1 (Part 1)

Romans

The first half of Romans 1 according to Paul's letter emphasizes that the gospel message was not new, but rather a fulfilled promise from the Old Test

Series by Steve Gregg

1 Corinthians

Steve Gregg provides a verse-by-verse exposition of 1 Corinthians, delving into themes such as love, spiritual gifts, holiness, and discipline within

Colossians

In this 8-part series from Steve Gregg, listeners are taken on an insightful journey through the book of Colossians, exploring themes of transformatio

Foundations of the Christian Faith

This series by Steve Gregg delves into the foundational beliefs of Christianity, including topics such as baptism, faith, repentance, resurrection, an

Genesis

Steve Gregg provides a detailed analysis of the book of Genesis in this 40-part series, exploring concepts of Christian discipleship, faith, obedience

Nehemiah

A comprehensive analysis by Steve Gregg on the book of Nehemiah, exploring the story of an ordinary man's determination and resilience in rebuilding t

How Can I Know That I Am Really Saved?

In this four-part series, Steve Gregg explores the concept of salvation using 1 John as a template and emphasizes the importance of love, faith, godli

1 Thessalonians

In this three-part series from Steve Gregg, he provides an in-depth analysis of 1 Thessalonians, touching on topics such as sexual purity, eschatology

2 John

This is a single-part Bible study on the book of 2 John by Steve Gregg. In it, he examines the authorship and themes of the letter, emphasizing the im

Word of Faith

"Word of Faith" by Steve Gregg is a four-part series that provides a detailed analysis and thought-provoking critique of the Word Faith movement's tea

Zephaniah

Experience the prophetic words of Zephaniah, written in 612 B.C., as Steve Gregg vividly brings to life the impending judgement, destruction, and hope

More on OpenTheo

Did God Create Us So He Wouldn’t Be Alone?

#STRask

November 3, 2025

Questions about whether God created us so he wouldn’t be alone, what he had before us, and a comparison between the Muslim view of God and the Christi

Keri Ingraham: School Choice and Education Reform

Knight & Rose Show

January 24, 2026

Wintery Knight and guest host Bonnie welcome Dr. Keri Ingraham to discuss school choice and education reform. They discuss the public school monopoly'

What Do You Think About Churches Advertising on Social Media?

#STRask

January 19, 2026

Questions about whether there’s an issue with churches advertising on social media, whether it’s weird if we pray along with a YouTuber, and whether C

How Can I Explain Modesty to My Daughter?

#STRask

November 27, 2025

Questions about how to explain modesty to a nine-year-old in a way that won’t cause shame about her body, and when and how to tell a child about a pre

Prove to Me That Jesus Is Not a Created Being

#STRask

January 26, 2026

Questions about why we should think Jesus is not a created being, and what it means to say God became fully human if part of being human means not bei

Does Open-Mindedness Require Studying Other Religions Before Becoming a Christian?

#STRask

February 9, 2026

Questions about the claim that if Christians really want to be open-minded, they need to read and study other religions before committing to Christian

The Heidelberg Catechism with R. Scott Clark

Life and Books and Everything

November 3, 2025

You may not think you need 1,000 pages on the Heidelberg Catechism, but you do! R. Scott Clark, professor at Westminster Seminary California, has writ

How Would You Convince Someone That Evil Exists?

#STRask

November 17, 2025

Questions about how to convince someone that evil exists, whether Charlie Kirk’s murder was part of God’s plan, whether that would mean the murderer d

Christmas Cranks and Christmas Blessings with Justin Taylor and Collin Hansen

Life and Books and Everything

December 17, 2025

If you are looking for a podcast where three friends talk about whatever they want to talk about and ramble on about sports, books, and grievances, th

The Resurrection Standoff: Licona vs. Ehrman on the Unbelievable Podcast

Risen Jesus

October 22, 2025

This episode is taken from the Unbelievable podcast with Justin Brierly in 2011 when Dr. Bart Ehrman and Dr. Michael Licona address the question: Is t

Are You Accursed If You Tithe?

#STRask

December 15, 2025

Questions about whether anyone who tithes is not a Christian and is accursed since Paul says that if you obey one part of the Mosaic Law you’re obliga

Is Greg Placing His Faith in the Wrong Thing?

#STRask

February 12, 2026

Questions about Greg placing his faith in his personal assessment of which truth claims best match reality rather than in the revelation of God in Jes

How Do I Determine Which Topics at Work Are Worth Commenting On?

#STRask

January 5, 2026

Questions about how to determine which topics at work are worth commenting on, and a good way to respond when you’re in a group Bible study and hear e

How Can We Know Who Is Teaching the Same Gospel Paul Taught?

#STRask

February 16, 2026

Questions about how we can know who is teaching the same gospel Paul taught, and whether or not Jeremiah 1:5 supports the idea that we pre-existed in

Can You Provide Verifiable, Non-Religious Evidence That a Supernatural Jesus Existed?

#STRask

November 10, 2025

Question about providing verifiable, non-religious evidence that a supernatural Jesus existed.

* I am an atheist and militantly anti-god-belief. Ho