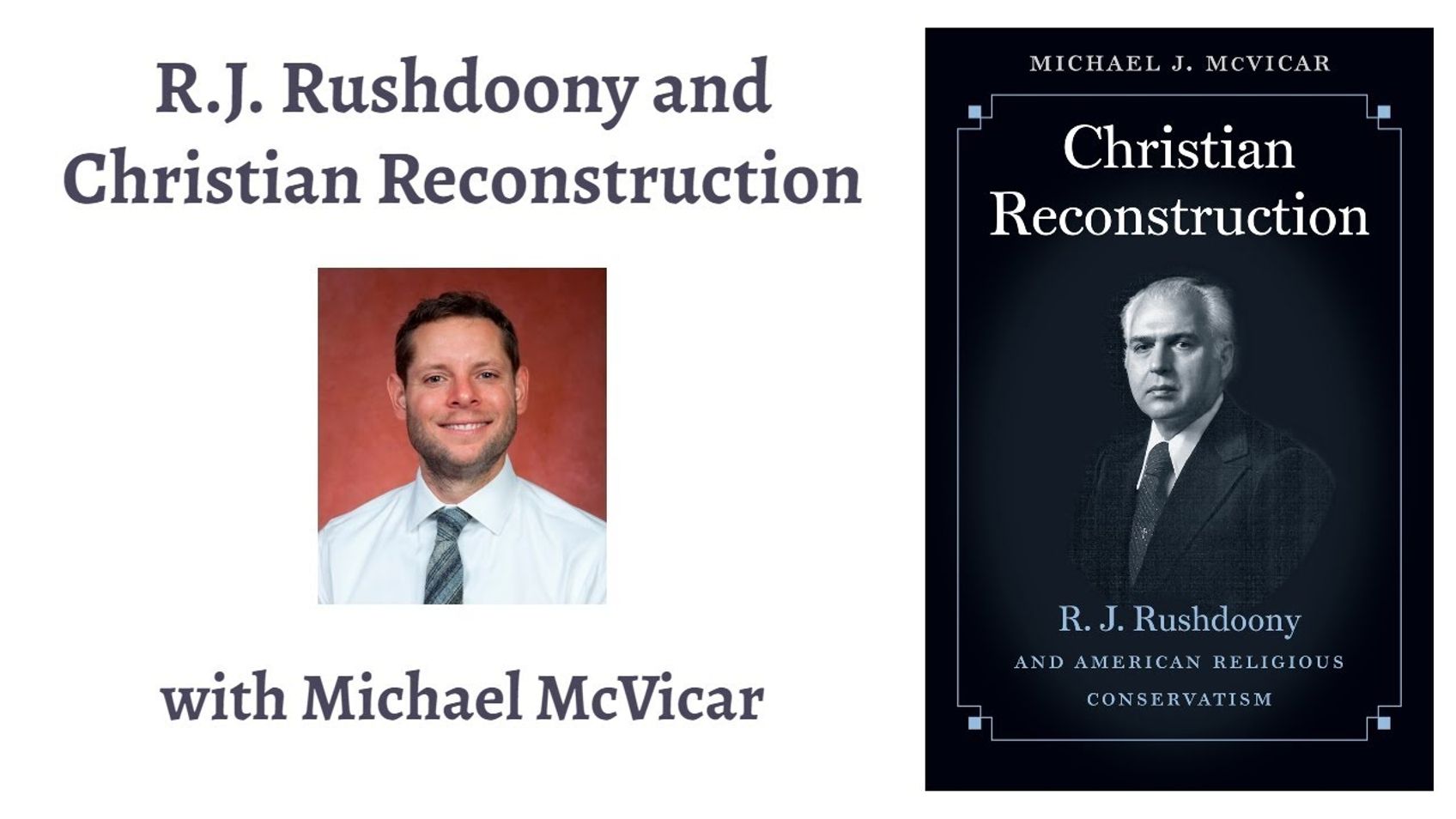

R.J. Rushdoony and Christian Reconstruction (with Michael McVicar)

August 13, 2020

Alastair Roberts

Michael McVicar, the author of 'Christian Reconstruction: R.J. Rushdoony and American Religious Conservatism' (https://amzn.to/3kErJ82), joins me to discuss R.J. Rushdoony and the movement that he started.

More From Alastair Roberts

August 14th: 2 Samuel 2 & Romans 14

Alastair Roberts

August 13, 2020

David becomes king of Judah and Ish-bosheth of Israel. Not judging our brother or causing him to stumble.

Reflections upon the readings from the ACNA

August 15th: 2 Samuel 3 & Luke 1:26-38

Alastair Roberts

August 14, 2020

Joab kills Abner. The Angel Gabriel appears to Mary.

Reflections upon the readings from the ACNA Book of Common Prayer (http://bcp2019.anglicanchurch

August 16th: 2 Samuel 4 & Romans 15

Alastair Roberts

August 15, 2020

The assassination of Ish-bosheth. Welcome one another as Christ has welcomed you.

Reflections upon the readings from the ACNA Book of Common Prayer (

August 13th: 2 Samuel 1 & Romans 13

Alastair Roberts

August 13, 2020

David's lament over Saul and Jonathan. Be subject to the governing authorities.

Reflections upon the readings from the ACNA Book of Common Prayer (ht

August 12th: 1 Samuel 31 & Romans 12

Alastair Roberts

August 12, 2020

The death of Saul. Present your bodies as a living sacrifice.

Reflections upon the readings from the ACNA Book of Common Prayer (http://bcp2019.angli

August 11th: 1 Samuel 30 & Romans 11

Alastair Roberts

August 10, 2020

David rescues the captives of the Amalekites. All Israel will be saved!

Reflections upon the readings from the ACNA Book of Common Prayer (http://bcp

More on OpenTheo

What About Those Who Never Heard the Name of Jesus?

#STRask

December 22, 2025

Questions about what will happen to those who never heard of Jesus or were brought up in a different faith, whether there’s biblical warrant to think

E. Calvin Beisner: Climate and Energy Policy

Knight & Rose Show

January 4, 2026

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose welcome Dr. E. Calvin Beisner to discuss climate and energy policy. They explore Biblical dominion and stewardship, con

Christmas Cranks and Christmas Blessings with Justin Taylor and Collin Hansen

Life and Books and Everything

December 17, 2025

If you are looking for a podcast where three friends talk about whatever they want to talk about and ramble on about sports, books, and grievances, th

Are You Accursed If You Tithe?

#STRask

December 15, 2025

Questions about whether anyone who tithes is not a Christian and is accursed since Paul says that if you obey one part of the Mosaic Law you’re obliga

What Is Wrong with Wokeness? With Neil Shenvi

Life and Books and Everything

January 19, 2026

In this timely interview, Kevin talks to Neil Shenvi about his new book (co-authored with Pat Sawyer), entitled “Post Woke: Asserting a Biblical Visio

When I Can’t Stop Thinking About Something, Is That God Speaking?

#STRask

December 1, 2025

Questions about whether having a recurring thought is an indication God is speaking to you, what to say to someone who says they sinned because “God t

What Tools of Reasoning Help You Know What’s True, Right, and Good?

#STRask

December 4, 2025

Question about what tools of reasoning help us determine whether something is true or false, right or wrong, good or bad before bringing Scripture int

Is 1 Corinthians 12:3 a Black-and-White Tool for Discernment?

#STRask

October 27, 2025

Questions about whether the claim in 1 Corinthians that “no one can say ‘Jesus is Lord’ except in the Holy Spirit” is a black-and-white tool for disce

How Do You Justify Calling Jesus the Messiah?

#STRask

December 18, 2025

Questions about how one can justify calling Jesus the Messiah when he didn’t fulfill the Hebrew messianic prophecies, and whether the reason for the v

Kingdom Priorities: Following the Teachings of Jesus

Knight & Rose Show

February 14, 2026

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose discuss Jesus' teachings from the Gospels, emphasizing truth, evidence, self-denial, and forgiveness. They explore pass

How Does It Affect You If a Gay Couple Gets Married or a Woman Has an Abortion?

#STRask

October 16, 2025

Questions about how to respond to someone who asks, ”How does it affect you if a gay couple gets married, or a woman makes a decision about her reprod

What Do You Think About Churches Advertising on Social Media?

#STRask

January 19, 2026

Questions about whether there’s an issue with churches advertising on social media, whether it’s weird if we pray along with a YouTuber, and whether C

The Making of the American Mind with Matthew Spalding

Life and Books and Everything

February 2, 2026

The United States is unique in how much attention it pays to its founding, its founders, and its founding documents. Arguably, the most famous and mos

Is It Possible There’s a Being That’s Greater Than God?

#STRask

February 5, 2026

Questions about whether it’s possible there’s a being that’s greater than God and that’s outside of God’s comprehension and omniscience, and how to ex

Conservatism and Religious Freedom with John Wilsey

Life and Books and Everything

October 27, 2025

What is conservatism? And why does it go hand in hand with religious freedom? How should we think about the American experiment of ordered liberty? Ha