Communion (Part 1)

Individual TopicsSteve Gregg

In "Communion (Part 1)" by Steve Gregg, different views on the practice of Communion, also known as the Eucharist, among various Christian denominations are discussed. While the Catholic view involves the transformation of the bread and wine into the literal body and blood of Jesus Christ, Protestant views are more varied. The speaker emphasizes the importance of faith and critical analysis of religious texts while questioning the Biblical support for the Catholic view of transubstantiation, ultimately stating that the Eucharist is a commemoration and remembrance of Christ rather than a literal consumption of his body and blood.

More from Individual Topics

23 of 111

Next in this series

Communion (Part 2)

Individual Topics

In "Communion (Part 2)", Steve Gregg explores the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation, which claims that the bread and wine consumed during commun

24 of 111

Cults (Part 1)

Individual Topics

In "Cults (Part 1)," Steve Gregg distinguishes cults from mainstream Christianity by significant theological differences, including beliefs about the

21 of 111

Christian Response to Gay Marriage

Individual Topics

In "Christian Response to Gay Marriage," Steve Gregg argues for the biblical definition of marriage as a divine institution between one man and one wo

Series by Steve Gregg

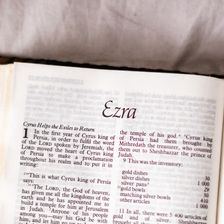

Ezra

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the book of Ezra, providing historical context, insights, and commentary on the challenges faced by the Jew

Isaiah: A Topical Look At Isaiah

In this 15-part series, Steve Gregg examines the key themes and ideas that recur throughout the book of Isaiah, discussing topics such as the remnant,

Gospel of Luke

In this 32-part series, Steve Gregg provides in-depth commentary and historical context on each chapter of the Gospel of Luke, shedding new light on i

Habakkuk

In his series "Habakkuk," Steve Gregg delves into the biblical book of Habakkuk, addressing the prophet's questions about God's actions during a troub

What You Absolutely Need To Know Before You Get Married

Steve Gregg's lecture series on marriage emphasizes the gravity of the covenant between two individuals and the importance of understanding God's defi

When Shall These Things Be?

In this 14-part series, Steve Gregg challenges commonly held beliefs within Evangelical Church on eschatology topics like the rapture, millennium, and

Knowing God

Knowing God by Steve Gregg is a 16-part series that delves into the dynamics of relationships with God, exploring the importance of walking with Him,

Psalms

In this 32-part series, Steve Gregg provides an in-depth verse-by-verse analysis of various Psalms, highlighting their themes, historical context, and

Survey of the Life of Christ

Steve Gregg's 9-part series explores various aspects of Jesus' life and teachings, including his genealogy, ministry, opposition, popularity, pre-exis

Nehemiah

A comprehensive analysis by Steve Gregg on the book of Nehemiah, exploring the story of an ordinary man's determination and resilience in rebuilding t

More on OpenTheo

Can You Provide Verifiable, Non-Religious Evidence That a Supernatural Jesus Existed?

#STRask

November 10, 2025

Question about providing verifiable, non-religious evidence that a supernatural Jesus existed.

* I am an atheist and militantly anti-god-belief. Ho

Keri Ingraham: School Choice and Education Reform

Knight & Rose Show

January 24, 2026

Wintery Knight and guest host Bonnie welcome Dr. Keri Ingraham to discuss school choice and education reform. They discuss the public school monopoly'

Can Two Logical People Come to Conflicting Conclusions Without Committing a Fallacy?

#STRask

January 8, 2026

Questions about whether two logical people can come to conflicting conclusions on a topic without committing a fallacy, how Greg, as a public figure,

How Can We Know Who Is Teaching the Same Gospel Paul Taught?

#STRask

February 16, 2026

Questions about how we can know who is teaching the same gospel Paul taught, and whether or not Jeremiah 1:5 supports the idea that we pre-existed in

How Would You Convince Someone That Evil Exists?

#STRask

November 17, 2025

Questions about how to convince someone that evil exists, whether Charlie Kirk’s murder was part of God’s plan, whether that would mean the murderer d

Did Jesus Prove He Wasn’t Sinless When He Overturned the Tables?

#STRask

December 29, 2025

Questions about whether Jesus proved he wasn’t sinless when he overturned the tables, whether Jesus’ response to the Pharisees in Mark 3:22–26 was a b

The Heidelberg Catechism with R. Scott Clark

Life and Books and Everything

November 3, 2025

You may not think you need 1,000 pages on the Heidelberg Catechism, but you do! R. Scott Clark, professor at Westminster Seminary California, has writ

How Do I Determine Which Topics at Work Are Worth Commenting On?

#STRask

January 5, 2026

Questions about how to determine which topics at work are worth commenting on, and a good way to respond when you’re in a group Bible study and hear e

Is 1 Corinthians 12:3 a Black-and-White Tool for Discernment?

#STRask

October 27, 2025

Questions about whether the claim in 1 Corinthians that “no one can say ‘Jesus is Lord’ except in the Holy Spirit” is a black-and-white tool for disce

What Is the Role of the Holy Spirit in Our Lives if He Doesn’t Give Us Instructions?

#STRask

February 23, 2026

Questions about the role of the Holy Spirit in our lives, advice for someone who believes in God intellectually but struggles to understand how to hav

Are Demon Possessions and Exorcisms in the New Testament Literal?

#STRask

December 11, 2025

Questions about whether references to demon possessions and exorcisms in the New Testament are literal, how to talk to young children about ghosts, an

What Is Wrong with Wokeness? With Neil Shenvi

Life and Books and Everything

January 19, 2026

In this timely interview, Kevin talks to Neil Shenvi about his new book (co-authored with Pat Sawyer), entitled “Post Woke: Asserting a Biblical Visio

An Invitation to the 2026 Coram Deo Pastors Conference

Life and Books and Everything

February 18, 2026

"I love being a pastor, and I love pastors, which is why I hope you will consider joining us at the Coram Deo Pastors Conference in 2026." —Kevin DeYo

Protestants and Catholics: What’s the Difference? With Chad Van Dixhoorn, Blair Smith, and Mark McDowell

Life and Books and Everything

November 26, 2025

How should Protestants think about the Catholic Mass? About the Eucharist? About the history and development of the papacy? In this panel discussion,

Does Open-Mindedness Require Studying Other Religions Before Becoming a Christian?

#STRask

February 9, 2026

Questions about the claim that if Christians really want to be open-minded, they need to read and study other religions before committing to Christian