How to Study the Bible (Part 1)

Individual Topics — Steve GreggNext in this series

How to Study the Bible (Part 2)

How to Study the Bible (Part 1)

Individual TopicsSteve Gregg

Steve Gregg provides insights on how to study the Bible effectively by discussing the importance of understanding the Bible correctly, attaching faith, familiarity with the Bible, choosing the right version, and considering translation philosophy and manuscript choice. He also highlights various resources such as annotated study Bibles, Greek and Hebrew dictionaries, and commentaries that can help in understanding the true meaning of the text. Thus, through disciplined study, Christians can gain essential knowledge of the Bible's teachings and enhance their spiritual growth.

More from Individual Topics

42 of 111

Next in this series

How to Study the Bible (Part 2)

Individual Topics

In this discourse, Steve Gregg outlines important steps to studying the Bible. He emphasizes the significance of becoming familiar with the text and u

43 of 111

How to Walk in the Spirit

Individual Topics

In this piece, Steve Gregg explores the concept of "walking in the spirit," which refers to living a life according to spiritual principles. He highli

40 of 111

How To Love Your Wife

Individual Topics

In this insightful talk, Steve Gregg delves into the importance of loving one's wife as Christ loves the church, acknowledging that the subject matter

Series by Steve Gregg

Gospel of Mark

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the Gospel of Mark.

The Narrow Path is the radio and internet ministry of Steve Gregg, a servant Bible tea

Philippians

In this 2-part series, Steve Gregg explores the book of Philippians, encouraging listeners to find true righteousness in Christ rather than relying on

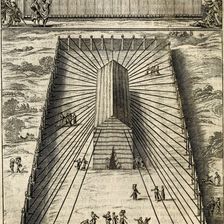

The Tabernacle

"The Tabernacle" is a comprehensive ten-part series that explores the symbolism and significance of the garments worn by priests, the construction and

James

A five-part series on the book of James by Steve Gregg focuses on practical instructions for godly living, emphasizing the importance of using words f

Knowing God

Knowing God by Steve Gregg is a 16-part series that delves into the dynamics of relationships with God, exploring the importance of walking with Him,

Esther

In this two-part series, Steve Gregg teaches through the book of Esther, discussing its historical significance and the story of Queen Esther's braver

Making Sense Out Of Suffering

In "Making Sense Out Of Suffering," Steve Gregg delves into the philosophical question of why a good sovereign God allows suffering in the world.

Leviticus

In this 12-part series, Steve Gregg provides insightful analysis of the book of Leviticus, exploring its various laws and regulations and offering spi

2 John

This is a single-part Bible study on the book of 2 John by Steve Gregg. In it, he examines the authorship and themes of the letter, emphasizing the im

Bible Book Overviews

Steve Gregg provides comprehensive overviews of books in the Old and New Testaments, highlighting key themes, messages, and prophesies while exploring

More on OpenTheo

The Making of the American Mind with Matthew Spalding

Life and Books and Everything

February 2, 2026

The United States is unique in how much attention it pays to its founding, its founders, and its founding documents. Arguably, the most famous and mos

Protestants and Catholics: What’s the Difference? With Chad Van Dixhoorn, Blair Smith, and Mark McDowell

Life and Books and Everything

November 26, 2025

How should Protestants think about the Catholic Mass? About the Eucharist? About the history and development of the papacy? In this panel discussion,

Is It Possible There’s a Being That’s Greater Than God?

#STRask

February 5, 2026

Questions about whether it’s possible there’s a being that’s greater than God and that’s outside of God’s comprehension and omniscience, and how to ex

Are Demon Possessions and Exorcisms in the New Testament Literal?

#STRask

December 11, 2025

Questions about whether references to demon possessions and exorcisms in the New Testament are literal, how to talk to young children about ghosts, an

How Do We Advocate for Christian Policy Without Making the Government Interfere in Every Area of Life?

#STRask

November 20, 2025

Questions about how to advocate for Christian policy without making the government interfere in every area of life, and the differences between the mo

The Heidelberg Catechism with R. Scott Clark

Life and Books and Everything

November 3, 2025

You may not think you need 1,000 pages on the Heidelberg Catechism, but you do! R. Scott Clark, professor at Westminster Seminary California, has writ

When I Can’t Stop Thinking About Something, Is That God Speaking?

#STRask

December 1, 2025

Questions about whether having a recurring thought is an indication God is speaking to you, what to say to someone who says they sinned because “God t

Are You Accursed If You Tithe?

#STRask

December 15, 2025

Questions about whether anyone who tithes is not a Christian and is accursed since Paul says that if you obey one part of the Mosaic Law you’re obliga

E. Calvin Beisner: Climate and Energy Policy

Knight & Rose Show

January 4, 2026

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose welcome Dr. E. Calvin Beisner to discuss climate and energy policy. They explore Biblical dominion and stewardship, con

Christmas Cranks and Christmas Blessings with Justin Taylor and Collin Hansen

Life and Books and Everything

December 17, 2025

If you are looking for a podcast where three friends talk about whatever they want to talk about and ramble on about sports, books, and grievances, th

Why Should We Pray If God Already Knows What’s Going to Happen?

#STRask

January 29, 2026

Questions about why we should pray if God already knows what’s going to happen, how the effectiveness of prayer is measured, and whether or not things

Can You Provide Verifiable, Non-Religious Evidence That a Supernatural Jesus Existed?

#STRask

November 10, 2025

Question about providing verifiable, non-religious evidence that a supernatural Jesus existed.

* I am an atheist and militantly anti-god-belief. Ho

What About Those Who Never Heard the Name of Jesus?

#STRask

December 22, 2025

Questions about what will happen to those who never heard of Jesus or were brought up in a different faith, whether there’s biblical warrant to think

Is 1 Corinthians 12:3 a Black-and-White Tool for Discernment?

#STRask

October 27, 2025

Questions about whether the claim in 1 Corinthians that “no one can say ‘Jesus is Lord’ except in the Holy Spirit” is a black-and-white tool for disce

Did Jesus Prove He Wasn’t Sinless When He Overturned the Tables?

#STRask

December 29, 2025

Questions about whether Jesus proved he wasn’t sinless when he overturned the tables, whether Jesus’ response to the Pharisees in Mark 3:22–26 was a b