How to Study the Bible (Part 2)

Individual Topics — Steve GreggNext in this series

How to Walk in the Spirit

How to Study the Bible (Part 2)

Individual TopicsSteve Gregg

In this discourse, Steve Gregg outlines important steps to studying the Bible. He emphasizes the significance of becoming familiar with the text and understanding it in its unique human language, which involves careful observation and questioning. He also highlights the importance of studying unfamiliar words and considering the context of a passage when interpreting it. Additionally, he stresses the need for humility and prayer in approaching biblical study, and the importance of applying the word of God in our lives for spiritual growth.

More from Individual Topics

43 of 111

Next in this series

How to Walk in the Spirit

Individual Topics

In this piece, Steve Gregg explores the concept of "walking in the spirit," which refers to living a life according to spiritual principles. He highli

44 of 111

Humility (Part 1)

Individual Topics

In his teachings, Steve Gregg emphasizes the importance of humility as a character trait for walking with God acceptably. Pride is considered a heinou

41 of 111

How to Study the Bible (Part 1)

Individual Topics

Steve Gregg provides insights on how to study the Bible effectively by discussing the importance of understanding the Bible correctly, attaching faith

Series by Steve Gregg

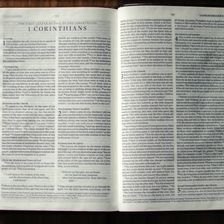

1 Corinthians

Steve Gregg provides a verse-by-verse exposition of 1 Corinthians, delving into themes such as love, spiritual gifts, holiness, and discipline within

Sermon on the Mount

Steve Gregg's 14-part series on the Sermon on the Mount deepens the listener's understanding of the Beatitudes and other teachings in Matthew 5-7, emp

Titus

In this four-part series from Steve Gregg, listeners are taken on an insightful journey through the book of Titus, exploring issues such as good works

James

A five-part series on the book of James by Steve Gregg focuses on practical instructions for godly living, emphasizing the importance of using words f

2 Samuel

Steve Gregg provides a verse-by-verse analysis of the book of 2 Samuel, focusing on themes, characters, and events and their relevance to modern-day C

Nahum

In the series "Nahum" by Steve Gregg, the speaker explores the divine judgment of God upon the wickedness of the city Nineveh during the Assyrian rule

Obadiah

Steve Gregg provides a thorough examination of the book of Obadiah, exploring the conflict between Israel and Edom and how it relates to divine judgem

Malachi

Steve Gregg's in-depth exploration of the book of Malachi provides insight into why the Israelites were not prospering, discusses God's election, and

Isaiah: A Topical Look At Isaiah

In this 15-part series, Steve Gregg examines the key themes and ideas that recur throughout the book of Isaiah, discussing topics such as the remnant,

Jonah

Steve Gregg's lecture on the book of Jonah focuses on the historical context of Nineveh, where Jonah was sent to prophesy repentance. He emphasizes th

More on OpenTheo

Did God Create Us So He Wouldn’t Be Alone?

#STRask

November 3, 2025

Questions about whether God created us so he wouldn’t be alone, what he had before us, and a comparison between the Muslim view of God and the Christi

The Man on the Middle Cross with Alistair Begg

Life and Books and Everything

November 10, 2025

If you haven’t seen the viral clip, go see it right now. In this episode, Kevin talks to Alistair about the preaching clip he didn’t intend to give, h

What Is Wrong with Wokeness? With Neil Shenvi

Life and Books and Everything

January 19, 2026

In this timely interview, Kevin talks to Neil Shenvi about his new book (co-authored with Pat Sawyer), entitled “Post Woke: Asserting a Biblical Visio

Shouldn’t I Be Praying for My Soul Rather Than for Material Things?

#STRask

February 2, 2026

Questions about whether we should be praying for our souls rather than for material things, why we need to pray about decisions, whether the devil can

Why Do We Say Someone Was Saved on a Particular Date If It Was Part of an Eternal Plan?

#STRask

November 24, 2025

Questions about why we say someone was saved on a particular date if it was part of an eternal plan, the Roman Catholic view of the gospel vs. the Bib

Are You Accursed If You Tithe?

#STRask

December 15, 2025

Questions about whether anyone who tithes is not a Christian and is accursed since Paul says that if you obey one part of the Mosaic Law you’re obliga

Christmas Cranks and Christmas Blessings with Justin Taylor and Collin Hansen

Life and Books and Everything

December 17, 2025

If you are looking for a podcast where three friends talk about whatever they want to talk about and ramble on about sports, books, and grievances, th

E. Calvin Beisner: Climate and Energy Policy

Knight & Rose Show

January 4, 2026

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose welcome Dr. E. Calvin Beisner to discuss climate and energy policy. They explore Biblical dominion and stewardship, con

Life and Ministry in Charlotte and in the SBC with Clint Pressley

Life and Books and Everything

December 15, 2025

In a rare cultural anomaly that may never be repeated in our lifetimes, the current SBC President and current PCA Moderator live in the same neighborh

What Are Some Good Ways to Start a Conversation About God with Family Members?

#STRask

October 30, 2025

Questions about how to start a conversation about God with non-Christian family members, how to keep from becoming emotional when discussing faith iss

Kingdom Priorities: Following the Teachings of Jesus

Knight & Rose Show

February 14, 2026

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose discuss Jesus' teachings from the Gospels, emphasizing truth, evidence, self-denial, and forgiveness. They explore pass

Why Should We Pray If God Already Knows What’s Going to Happen?

#STRask

January 29, 2026

Questions about why we should pray if God already knows what’s going to happen, how the effectiveness of prayer is measured, and whether or not things

Can You Recommend Good Books with More In-Depth Information and Ideas?

#STRask

January 22, 2026

Questions about good books on Christian apologetics, philosophy, and theology with more in-depth information and ideas, and resources to help an intel

The Heidelberg Catechism with R. Scott Clark

Life and Books and Everything

November 3, 2025

You may not think you need 1,000 pages on the Heidelberg Catechism, but you do! R. Scott Clark, professor at Westminster Seminary California, has writ

Did Jesus Prove He Wasn’t Sinless When He Overturned the Tables?

#STRask

December 29, 2025

Questions about whether Jesus proved he wasn’t sinless when he overturned the tables, whether Jesus’ response to the Pharisees in Mark 3:22–26 was a b