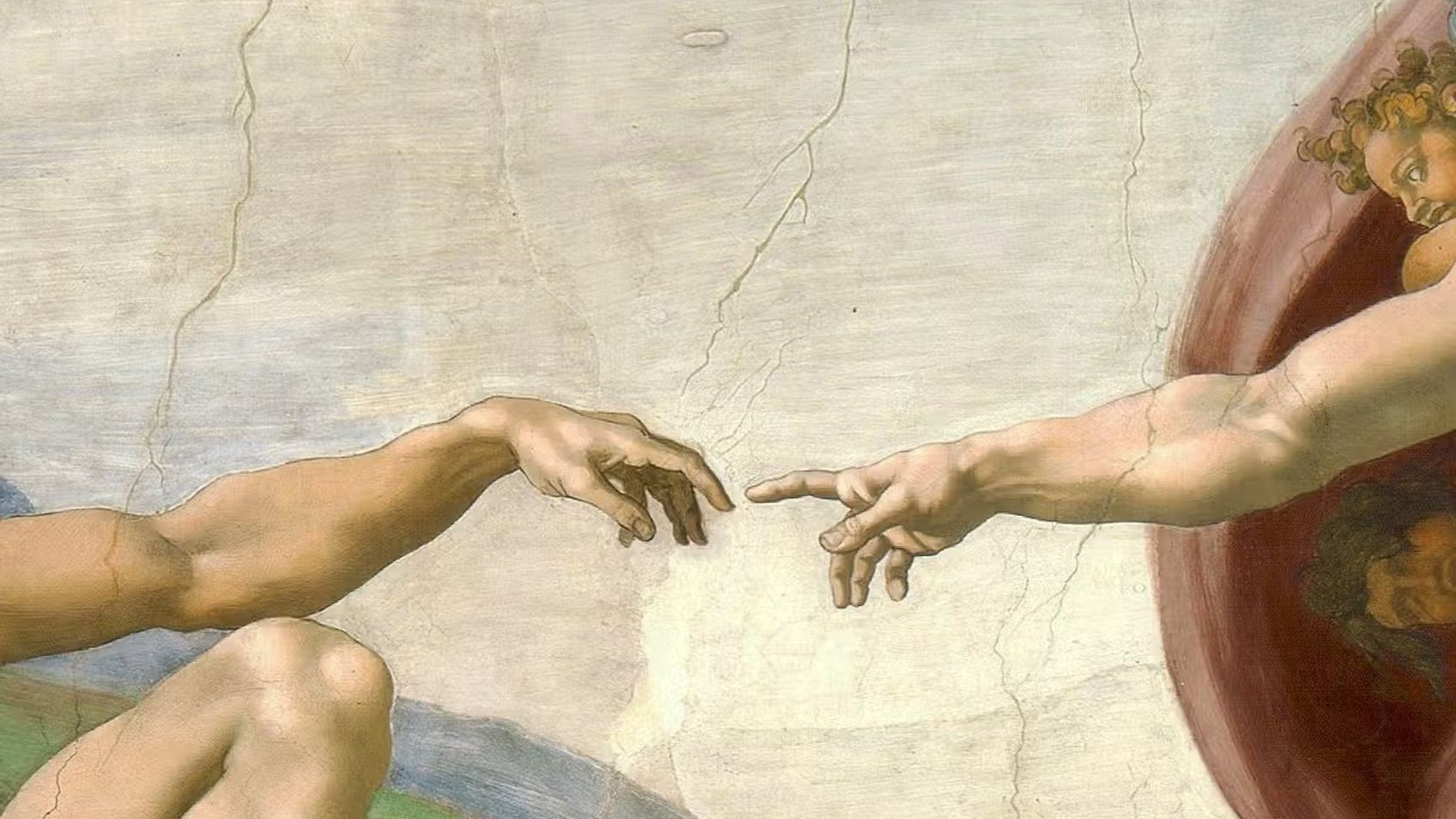

Evidence of Creation

Creation and EvolutionSteve Gregg

Steve Gregg presents evidence supporting the theory of creation by highlighting the absence of transitional forms in both the present and the fossil record. He emphasizes the complexity of seemingly simple structures like feathers, asserting that they defy analysis and cannot be adequately explained through evolution. Gregg raises questions about the development of advantageous traits in organisms and contends that the intricate behaviors and organization observed in animals and plants suggest the involvement of an intelligent creator. He concludes that the evidence challenges Darwinian theories and points towards a basis in intelligence rather than chance for the origin and diversity of life.

More from Creation and Evolution

3 of 4

Evidence Against Evolution

Creation and Evolution

Steve Gregg presents arguments against the theory of evolution by examining various evidences in support of creationism. He questions the notion that

Series by Steve Gregg

Hebrews

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the book of Hebrews, focusing on themes, warnings, the new covenant, judgment, faith, Jesus' authority, and

Church History

Steve Gregg gives a comprehensive overview of church history from the time of the Apostles to the modern day, covering important figures, events, move

Psalms

In this 32-part series, Steve Gregg provides an in-depth verse-by-verse analysis of various Psalms, highlighting their themes, historical context, and

1 Thessalonians

In this three-part series from Steve Gregg, he provides an in-depth analysis of 1 Thessalonians, touching on topics such as sexual purity, eschatology

Gospel of Luke

In this 32-part series, Steve Gregg provides in-depth commentary and historical context on each chapter of the Gospel of Luke, shedding new light on i

Strategies for Unity

"Strategies for Unity" is a 4-part series discussing the importance of Christian unity, overcoming division, promoting positive relationships, and pri

2 Timothy

In this insightful series on 2 Timothy, Steve Gregg explores the importance of self-control, faith, and sound doctrine in the Christian life, urging b

Some Assembly Required

Steve Gregg's focuses on the concept of the Church as a universal movement of believers, emphasizing the importance of community and loving one anothe

Three Views of Hell

Steve Gregg discusses the three different views held by Christians about Hell: the traditional view, universalism, and annihilationism. He delves into

Haggai

In Steve Gregg's engaging exploration of the book of Haggai, he highlights its historical context and key themes often overlooked in this prophetic wo

More on OpenTheo

What Tools of Reasoning Help You Know What’s True, Right, and Good?

#STRask

December 4, 2025

Question about what tools of reasoning help us determine whether something is true or false, right or wrong, good or bad before bringing Scripture int

Does God Really Need a “Pound of Flesh” to Forgive Sins?

#STRask

January 12, 2026

Questions about how to answer the challenge that God doesn’t need a “pound of flesh” to forgive sins but can simply forgive, and whether the claim in

Kingdom Priorities: Following the Teachings of Jesus

Knight & Rose Show

February 14, 2026

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose discuss Jesus' teachings from the Gospels, emphasizing truth, evidence, self-denial, and forgiveness. They explore pass

Why Does the Bible Teach You How to Be a Proper Slave Owner?

#STRask

November 13, 2025

Question about why it seems like the Bible teaches you how to be a proper slave owner rather than than saying, “Stop it. Give them freedom.”

* It s

How Can I Explain Modesty to My Daughter?

#STRask

November 27, 2025

Questions about how to explain modesty to a nine-year-old in a way that won’t cause shame about her body, and when and how to tell a child about a pre

Protestants and Catholics: What’s the Difference? With Chad Van Dixhoorn, Blair Smith, and Mark McDowell

Life and Books and Everything

November 26, 2025

How should Protestants think about the Catholic Mass? About the Eucharist? About the history and development of the papacy? In this panel discussion,

What Are Some Good Ways to Start a Conversation About God with Family Members?

#STRask

October 30, 2025

Questions about how to start a conversation about God with non-Christian family members, how to keep from becoming emotional when discussing faith iss

Is It a Sin to Feel Let Down by God?

#STRask

November 6, 2025

Questions about whether it’s a sin to feel let down by God and whether it would be easier to have a personal relationship with a rock than with a God

Life and Ministry in Charlotte and in the SBC with Clint Pressley

Life and Books and Everything

December 15, 2025

In a rare cultural anomaly that may never be repeated in our lifetimes, the current SBC President and current PCA Moderator live in the same neighborh

Are Demon Possessions and Exorcisms in the New Testament Literal?

#STRask

December 11, 2025

Questions about whether references to demon possessions and exorcisms in the New Testament are literal, how to talk to young children about ghosts, an

Why Do We Say Someone Was Saved on a Particular Date If It Was Part of an Eternal Plan?

#STRask

November 24, 2025

Questions about why we say someone was saved on a particular date if it was part of an eternal plan, the Roman Catholic view of the gospel vs. the Bib

Why Is It Necessary to Believe Jesus Is God?

#STRask

February 19, 2026

Questions about why it’s necessary to believe Jesus is God, whether belief in the Trinity is required for salvation, and why one has to believe in the

Did God Create Us So He Wouldn’t Be Alone?

#STRask

November 3, 2025

Questions about whether God created us so he wouldn’t be alone, what he had before us, and a comparison between the Muslim view of God and the Christi

Lora Ries: Border Security and Immigration Policy

Knight & Rose Show

December 7, 2025

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose welcome Lora Ries to discuss border security and immigration policy. They explore Biden's policy changes, like ending R

How Can We Know Who Is Teaching the Same Gospel Paul Taught?

#STRask

February 16, 2026

Questions about how we can know who is teaching the same gospel Paul taught, and whether or not Jeremiah 1:5 supports the idea that we pre-existed in