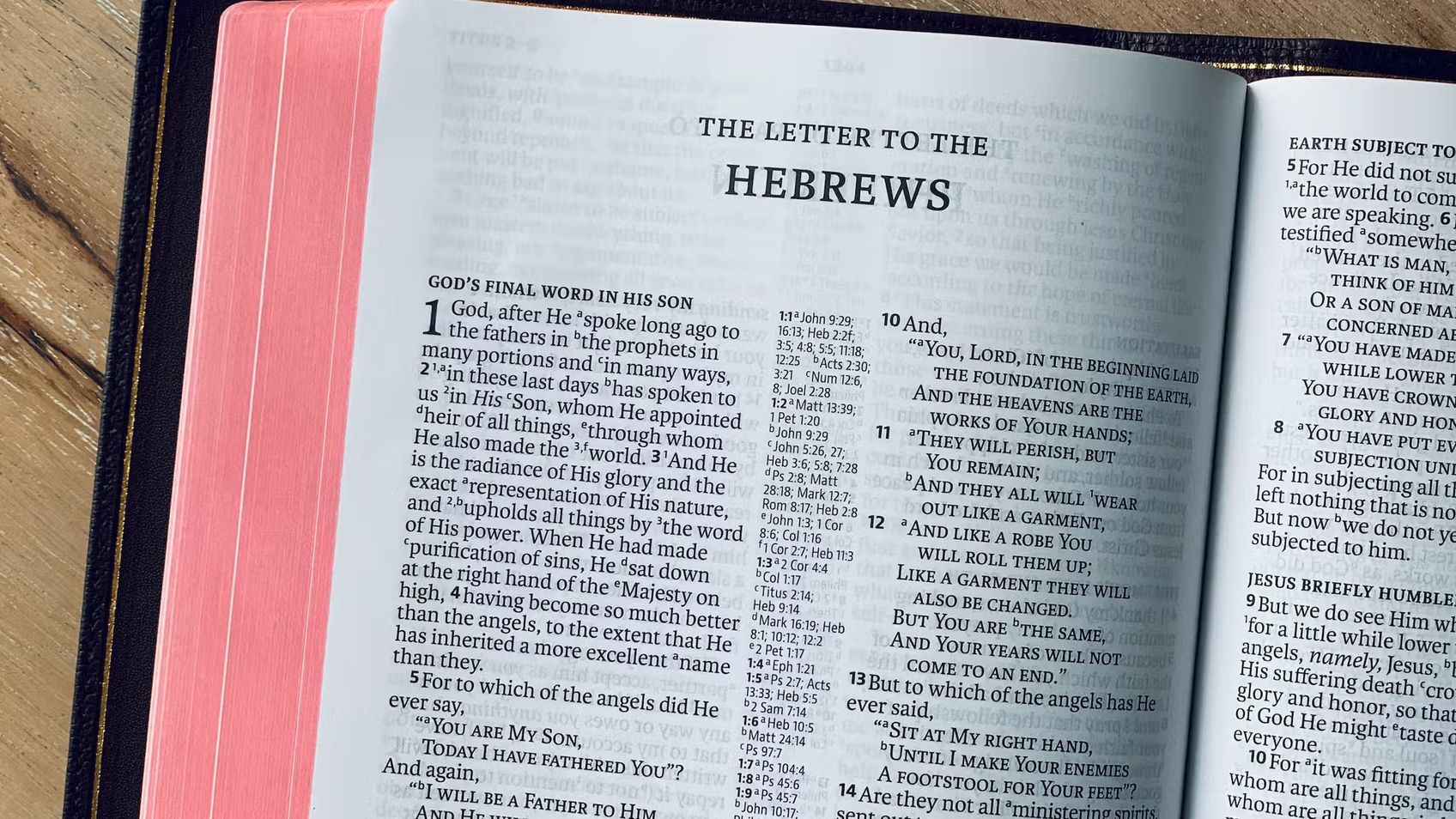

Hebrews Introduction (Part 1)

HebrewsSteve Gregg

In this introduction to the book of Hebrews, Steve Gregg reflects on the mysterious authorship of the book and its unique audience. He notes that although the book shares similarities with Paul's writings, it has distinct differences and is likely not his work. Gregg also discusses the book's arguments against the old Jewish sacrificial system and its emphasis on the once-for-all sacrifice of Jesus Christ. Ultimately, the book of Hebrews presents a tight and compelling argument for the superiority of Christ over all other spiritual authorities.

More from Hebrews

2 of 15

Next in this series

Hebrews Introduction (Part 2)

Hebrews

Steve Gregg explores the concept of judgment and its application both in the context of temporal punishment and the notion of eternal hell. He also de

3 of 15

Hebrews 1

Hebrews

Steve Gregg provides an examination of Hebrews 1, discussing how God spoke throughout the Old Testament era, particularly during the time of Moses. Th

Series by Steve Gregg

Creation and Evolution

In the series "Creation and Evolution" by Steve Gregg, the evidence against the theory of evolution is examined, questioning the scientific foundation

Kingdom of God

An 8-part series by Steve Gregg that explores the concept of the Kingdom of God and its various aspects, including grace, priesthood, present and futu

Gospel of John

In this 38-part series, Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the Gospel of John, providing insightful analysis and exploring important themes su

Cultivating Christian Character

Steve Gregg's lecture series focuses on cultivating holiness and Christian character, emphasizing the need to have God's character and to walk in the

2 Thessalonians

A thought-provoking biblical analysis by Steve Gregg on 2 Thessalonians, exploring topics such as the concept of rapture, martyrdom in church history,

Wisdom Literature

In this four-part series, Steve Gregg explores the wisdom literature of the Bible, emphasizing the importance of godly behavior and understanding the

Daniel

Steve Gregg discusses various parts of the book of Daniel, exploring themes of prophecy, historical accuracy, and the significance of certain events.

Biblical Counsel for a Change

"Biblical Counsel for a Change" is an 8-part series that explores the integration of psychology and Christianity, challenging popular notions of self-

Ezra

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the book of Ezra, providing historical context, insights, and commentary on the challenges faced by the Jew

Philemon

Steve Gregg teaches a verse-by-verse study of the book of Philemon, examining the historical context and themes, and drawing insights from Paul's pray

More on OpenTheo

How Do We Advocate for Christian Policy Without Making the Government Interfere in Every Area of Life?

#STRask

November 20, 2025

Questions about how to advocate for Christian policy without making the government interfere in every area of life, and the differences between the mo

Are Demon Possessions and Exorcisms in the New Testament Literal?

#STRask

December 11, 2025

Questions about whether references to demon possessions and exorcisms in the New Testament are literal, how to talk to young children about ghosts, an

What Are Some Good Ways to Start a Conversation About God with Family Members?

#STRask

October 30, 2025

Questions about how to start a conversation about God with non-Christian family members, how to keep from becoming emotional when discussing faith iss

Why Is It Necessary to Believe Jesus Is God?

#STRask

February 19, 2026

Questions about why it’s necessary to believe Jesus is God, whether belief in the Trinity is required for salvation, and why one has to believe in the

Why Do We Say Someone Was Saved on a Particular Date If It Was Part of an Eternal Plan?

#STRask

November 24, 2025

Questions about why we say someone was saved on a particular date if it was part of an eternal plan, the Roman Catholic view of the gospel vs. the Bib

Why Does the Bible Teach You How to Be a Proper Slave Owner?

#STRask

November 13, 2025

Question about why it seems like the Bible teaches you how to be a proper slave owner rather than than saying, “Stop it. Give them freedom.”

* It s

Kingdom Priorities: Following the Teachings of Jesus

Knight & Rose Show

February 14, 2026

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose discuss Jesus' teachings from the Gospels, emphasizing truth, evidence, self-denial, and forgiveness. They explore pass

The Heidelberg Catechism with R. Scott Clark

Life and Books and Everything

November 3, 2025

You may not think you need 1,000 pages on the Heidelberg Catechism, but you do! R. Scott Clark, professor at Westminster Seminary California, has writ

Protestants and Catholics: What’s the Difference? With Chad Van Dixhoorn, Blair Smith, and Mark McDowell

Life and Books and Everything

November 26, 2025

How should Protestants think about the Catholic Mass? About the Eucharist? About the history and development of the papacy? In this panel discussion,

What Is the Role of the Holy Spirit in Our Lives if He Doesn’t Give Us Instructions?

#STRask

February 23, 2026

Questions about the role of the Holy Spirit in our lives, advice for someone who believes in God intellectually but struggles to understand how to hav

Why Are So Many Christians Condemning LGB People Just Because of How They Love?

#STRask

January 15, 2026

Questions about Christians condemning LGB people just because of how they love, how God can expect someone to be celibate when others are free to marr

The Resurrection Standoff: Licona vs. Ehrman on the Unbelievable Podcast

Risen Jesus

October 22, 2025

This episode is taken from the Unbelievable podcast with Justin Brierly in 2011 when Dr. Bart Ehrman and Dr. Michael Licona address the question: Is t

Is It Possible There’s a Being That’s Greater Than God?

#STRask

February 5, 2026

Questions about whether it’s possible there’s a being that’s greater than God and that’s outside of God’s comprehension and omniscience, and how to ex

Shouldn’t I Be Praying for My Soul Rather Than for Material Things?

#STRask

February 2, 2026

Questions about whether we should be praying for our souls rather than for material things, why we need to pray about decisions, whether the devil can

The Making of the American Mind with Matthew Spalding

Life and Books and Everything

February 2, 2026

The United States is unique in how much attention it pays to its founding, its founders, and its founding documents. Arguably, the most famous and mos