Hebrews Introduction (Part 2)

HebrewsSteve Gregg

Steve Gregg explores the concept of judgment and its application both in the context of temporal punishment and the notion of eternal hell. He also delves into the idea that the temple and the old covenant would eventually disappear, replaced by the new covenant established by Jesus Christ, who is considered a high priest and the ultimate revelation of God. Gregg also highlights the significance of the priesthood established by Jesus, which differs from its Jewish counterpart, and emphasizes the importance of not neglecting God's call or neglecting the magnitude of the privileges that come with salvation.

More from Hebrews

3 of 15

Next in this series

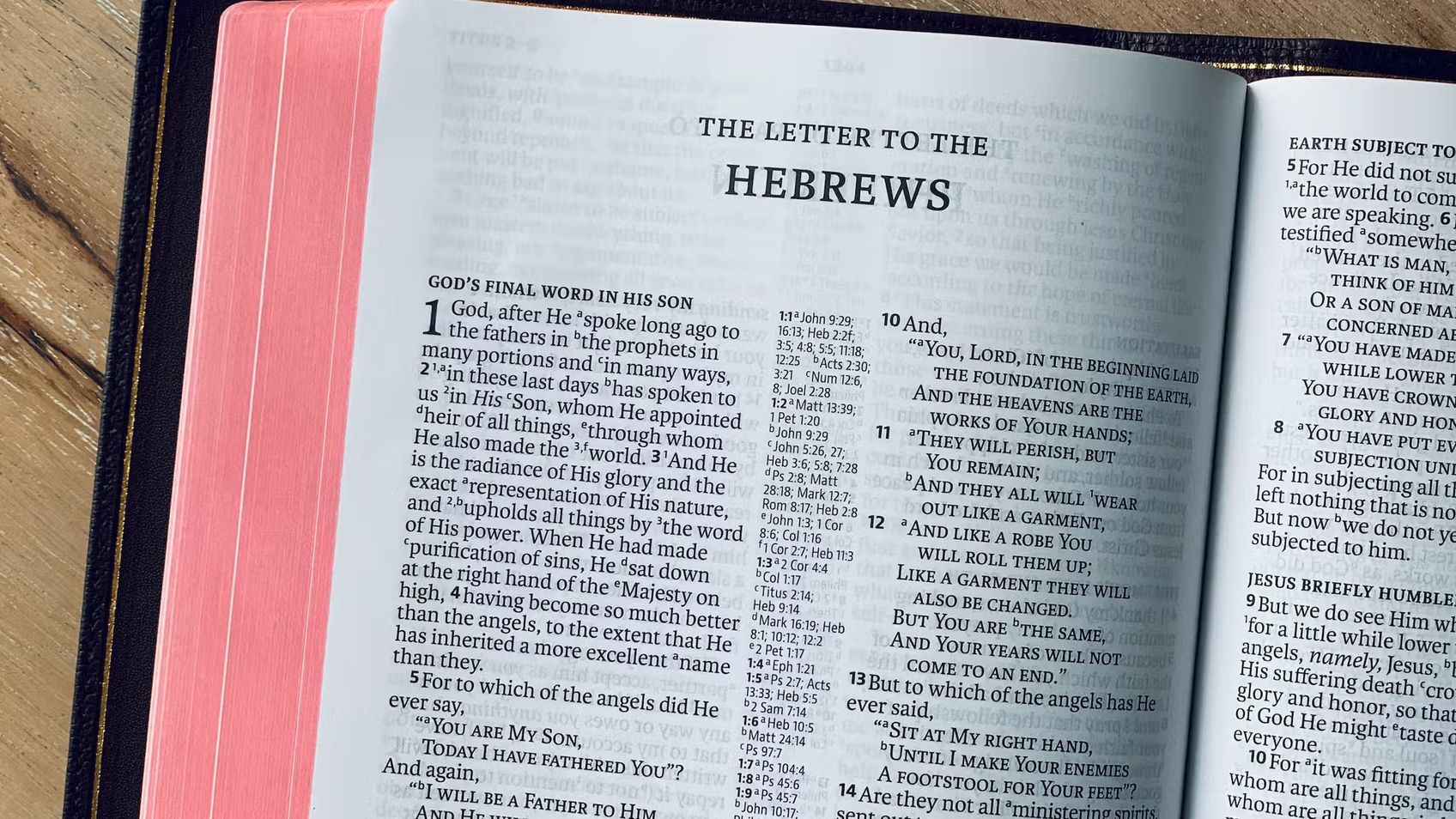

Hebrews 1

Hebrews

Steve Gregg provides an examination of Hebrews 1, discussing how God spoke throughout the Old Testament era, particularly during the time of Moses. Th

4 of 15

Hebrews 2

Hebrews

In this lecture, Steve Gregg explores the second chapter of Hebrews, which focuses on Jesus as a superior revelation of God. Gregg emphasizes the impo

1 of 15

Hebrews Introduction (Part 1)

Hebrews

In this introduction to the book of Hebrews, Steve Gregg reflects on the mysterious authorship of the book and its unique audience. He notes that alth

Series by Steve Gregg

Obadiah

Steve Gregg provides a thorough examination of the book of Obadiah, exploring the conflict between Israel and Edom and how it relates to divine judgem

Torah Observance

In this 4-part series titled "Torah Observance," Steve Gregg explores the significance and spiritual dimensions of adhering to Torah teachings within

Church History

Steve Gregg gives a comprehensive overview of church history from the time of the Apostles to the modern day, covering important figures, events, move

What You Absolutely Need To Know Before You Get Married

Steve Gregg's lecture series on marriage emphasizes the gravity of the covenant between two individuals and the importance of understanding God's defi

Job

In this 11-part series, Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the book of Job, discussing topics such as suffering, wisdom, and God's role in hum

Genesis

Steve Gregg provides a detailed analysis of the book of Genesis in this 40-part series, exploring concepts of Christian discipleship, faith, obedience

Ruth

Steve Gregg provides insightful analysis on the biblical book of Ruth, exploring its historical context, themes of loyalty and redemption, and the cul

Charisma and Character

In this 16-part series, Steve Gregg discusses various gifts of the Spirit, including prophecy, joy, peace, and humility, and emphasizes the importance

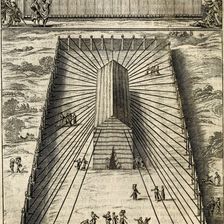

The Tabernacle

"The Tabernacle" is a comprehensive ten-part series that explores the symbolism and significance of the garments worn by priests, the construction and

The Life and Teachings of Christ

This 180-part series by Steve Gregg delves into the life and teachings of Christ, exploring topics such as prayer, humility, resurrection appearances,

More on OpenTheo

Is It a Sin to Feel Let Down by God?

#STRask

November 6, 2025

Questions about whether it’s a sin to feel let down by God and whether it would be easier to have a personal relationship with a rock than with a God

Is 1 Corinthians 12:3 a Black-and-White Tool for Discernment?

#STRask

October 27, 2025

Questions about whether the claim in 1 Corinthians that “no one can say ‘Jesus is Lord’ except in the Holy Spirit” is a black-and-white tool for disce

What Do You Think About Churches Advertising on Social Media?

#STRask

January 19, 2026

Questions about whether there’s an issue with churches advertising on social media, whether it’s weird if we pray along with a YouTuber, and whether C

Could the Writers of Scripture Have Been Influenced by Their Fallen Nature?

#STRask

October 23, 2025

Questions about whether or not it’s reasonable to worry that some of our current doctrines were influenced by the fallen nature of the apostles, and h

Why Do We Say Someone Was Saved on a Particular Date If It Was Part of an Eternal Plan?

#STRask

November 24, 2025

Questions about why we say someone was saved on a particular date if it was part of an eternal plan, the Roman Catholic view of the gospel vs. the Bib

How Would You Convince Someone That Evil Exists?

#STRask

November 17, 2025

Questions about how to convince someone that evil exists, whether Charlie Kirk’s murder was part of God’s plan, whether that would mean the murderer d

Sense, Sensibility, and Adam Smith with Jan Van Vliet

Life and Books and Everything

February 16, 2026

This year is a special anniversary for the United States as Americans celebrate 250 years of independence. But 1776 was an important year in more ways

How Can We Know Who Is Teaching the Same Gospel Paul Taught?

#STRask

February 16, 2026

Questions about how we can know who is teaching the same gospel Paul taught, and whether or not Jeremiah 1:5 supports the idea that we pre-existed in

Christmas Cranks and Christmas Blessings with Justin Taylor and Collin Hansen

Life and Books and Everything

December 17, 2025

If you are looking for a podcast where three friends talk about whatever they want to talk about and ramble on about sports, books, and grievances, th

Can You Recommend Good Books with More In-Depth Information and Ideas?

#STRask

January 22, 2026

Questions about good books on Christian apologetics, philosophy, and theology with more in-depth information and ideas, and resources to help an intel

An Invitation to the 2026 Coram Deo Pastors Conference

Life and Books and Everything

February 18, 2026

"I love being a pastor, and I love pastors, which is why I hope you will consider joining us at the Coram Deo Pastors Conference in 2026." —Kevin DeYo

What About Those Who Never Heard the Name of Jesus?

#STRask

December 22, 2025

Questions about what will happen to those who never heard of Jesus or were brought up in a different faith, whether there’s biblical warrant to think

Did God Create Us So He Wouldn’t Be Alone?

#STRask

November 3, 2025

Questions about whether God created us so he wouldn’t be alone, what he had before us, and a comparison between the Muslim view of God and the Christi

The Resurrection Standoff: Licona vs. Ehrman on the Unbelievable Podcast

Risen Jesus

October 22, 2025

This episode is taken from the Unbelievable podcast with Justin Brierly in 2011 when Dr. Bart Ehrman and Dr. Michael Licona address the question: Is t

Conservatism and Religious Freedom with John Wilsey

Life and Books and Everything

October 27, 2025

What is conservatism? And why does it go hand in hand with religious freedom? How should we think about the American experiment of ordered liberty? Ha