Passing the Torch

Church HistorySteve Gregg

In "Passing the Torch," Steve Gregg discusses the apostolic period of the church, emphasizing the work of the Holy Spirit and the formation of the body of Christ. Gregg notes the importance of avoiding confusion between the work of the Spirit and the organization of the church, and warns against the tendency towards legalism and mystical practices. He also touches on early church heresies and the influence of James, who played a significant role in establishing the authority of the Jerusalem church. Overall, Gregg emphasizes the important role of the apostles in establishing the norms and authority of the church.

More from Church History

4 of 30

Next in this series

Persecution and Ecclesiastical Development

Church History

Steve Gregg discusses the development of the Christian Church and the reasons for the persecution faced by early Christians. He notes that the origins

5 of 30

Early Heresies

Church History

Steve Gregg discusses early Christian heresies in this talk. He explains that some people defected from the faith, and contemporary apostles who lived

2 of 30

The Very Beginning

Church History

In "The Very Beginning," Steve Gregg explores the early days of the Christian church and its relationship to the Jewish synagogue. He notes that while

Series by Steve Gregg

2 Corinthians

This series by Steve Gregg is a verse-by-verse study through 2 Corinthians, covering various themes such as new creation, justification, comfort durin

Obadiah

Steve Gregg provides a thorough examination of the book of Obadiah, exploring the conflict between Israel and Edom and how it relates to divine judgem

Isaiah: A Topical Look At Isaiah

In this 15-part series, Steve Gregg examines the key themes and ideas that recur throughout the book of Isaiah, discussing topics such as the remnant,

Original Sin & Depravity

In this two-part series by Steve Gregg, he explores the theological concepts of Original Sin and Human Depravity, delving into different perspectives

Ecclesiastes

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the book of Ecclesiastes, exploring its themes of mortality, the emptiness of worldly pursuits, and the imp

Torah Observance

In this 4-part series titled "Torah Observance," Steve Gregg explores the significance and spiritual dimensions of adhering to Torah teachings within

2 Thessalonians

A thought-provoking biblical analysis by Steve Gregg on 2 Thessalonians, exploring topics such as the concept of rapture, martyrdom in church history,

Toward a Radically Christian Counterculture

Steve Gregg presents a vision for building a distinctive and holy Christian culture that stands in opposition to the values of the surrounding secular

Jonah

Steve Gregg's lecture on the book of Jonah focuses on the historical context of Nineveh, where Jonah was sent to prophesy repentance. He emphasizes th

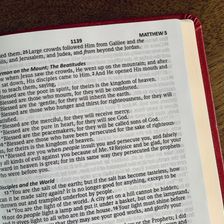

The Beatitudes

Steve Gregg teaches through the Beatitudes in Jesus' Sermon on the Mount.

More on OpenTheo

Can You Provide Verifiable, Non-Religious Evidence That a Supernatural Jesus Existed?

#STRask

November 10, 2025

Question about providing verifiable, non-religious evidence that a supernatural Jesus existed.

* I am an atheist and militantly anti-god-belief. Ho

Why Are So Many Christians Condemning LGB People Just Because of How They Love?

#STRask

January 15, 2026

Questions about Christians condemning LGB people just because of how they love, how God can expect someone to be celibate when others are free to marr

The Heidelberg Catechism with R. Scott Clark

Life and Books and Everything

November 3, 2025

You may not think you need 1,000 pages on the Heidelberg Catechism, but you do! R. Scott Clark, professor at Westminster Seminary California, has writ

The Making of the American Mind with Matthew Spalding

Life and Books and Everything

February 2, 2026

The United States is unique in how much attention it pays to its founding, its founders, and its founding documents. Arguably, the most famous and mos

Is Greg Placing His Faith in the Wrong Thing?

#STRask

February 12, 2026

Questions about Greg placing his faith in his personal assessment of which truth claims best match reality rather than in the revelation of God in Jes

Shouldn’t I Be Praying for My Soul Rather Than for Material Things?

#STRask

February 2, 2026

Questions about whether we should be praying for our souls rather than for material things, why we need to pray about decisions, whether the devil can

How Do You Justify Calling Jesus the Messiah?

#STRask

December 18, 2025

Questions about how one can justify calling Jesus the Messiah when he didn’t fulfill the Hebrew messianic prophecies, and whether the reason for the v

Can Two Logical People Come to Conflicting Conclusions Without Committing a Fallacy?

#STRask

January 8, 2026

Questions about whether two logical people can come to conflicting conclusions on a topic without committing a fallacy, how Greg, as a public figure,

Sense, Sensibility, and Adam Smith with Jan Van Vliet

Life and Books and Everything

February 16, 2026

This year is a special anniversary for the United States as Americans celebrate 250 years of independence. But 1776 was an important year in more ways

What Do You Think About Churches Advertising on Social Media?

#STRask

January 19, 2026

Questions about whether there’s an issue with churches advertising on social media, whether it’s weird if we pray along with a YouTuber, and whether C

How Can I Explain Modesty to My Daughter?

#STRask

November 27, 2025

Questions about how to explain modesty to a nine-year-old in a way that won’t cause shame about her body, and when and how to tell a child about a pre

Why Would Any Rational Person Have to Use Any Religious Book?

#STRask

December 8, 2025

Questions about why any rational person would have to use any religious book, whether apologetics would be redundant if there were actually a good, un

Lora Ries: Border Security and Immigration Policy

Knight & Rose Show

December 7, 2025

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose welcome Lora Ries to discuss border security and immigration policy. They explore Biden's policy changes, like ending R

What Is Wrong with Wokeness? With Neil Shenvi

Life and Books and Everything

January 19, 2026

In this timely interview, Kevin talks to Neil Shenvi about his new book (co-authored with Pat Sawyer), entitled “Post Woke: Asserting a Biblical Visio

The Resurrection Standoff: Licona vs. Ehrman on the Unbelievable Podcast

Risen Jesus

October 22, 2025

This episode is taken from the Unbelievable podcast with Justin Brierly in 2011 when Dr. Bart Ehrman and Dr. Michael Licona address the question: Is t