Early Heresies

Church HistorySteve Gregg

Steve Gregg discusses early Christian heresies in this talk. He explains that some people defected from the faith, and contemporary apostles who lived in the later centuries and died early on. He mentions several early Christian figures such as Hermas, Ignatius, Polycarp, and Papias. Steve delves into the heretical ideas that began to spread in the second century, including variations of Gnosticism and the modalistic theology of Li's cult. He explores key texts and doctrines, and highlights the various controversies that arose in the early Christian church.

More from Church History

6 of 30

Next in this series

The Canon of Scripture

Church History

Steve Gregg provides insights into the formation of the New Testament and the Canon of Scripture. He argues that none of the books of the Bible were l

7 of 30

Early Theologians

Church History

Steve Gregg discusses the rise of monasticism and the emergence of the earliest Christian theologians in the second to fourth centuries. He explains t

4 of 30

Persecution and Ecclesiastical Development

Church History

Steve Gregg discusses the development of the Christian Church and the reasons for the persecution faced by early Christians. He notes that the origins

Series by Steve Gregg

Torah Observance

In this 4-part series titled "Torah Observance," Steve Gregg explores the significance and spiritual dimensions of adhering to Torah teachings within

Introduction to the Life of Christ

Introduction to the Life of Christ by Steve Gregg is a four-part series that explores the historical background of the New Testament, sheds light on t

Zephaniah

Experience the prophetic words of Zephaniah, written in 612 B.C., as Steve Gregg vividly brings to life the impending judgement, destruction, and hope

Strategies for Unity

"Strategies for Unity" is a 4-part series discussing the importance of Christian unity, overcoming division, promoting positive relationships, and pri

Bible Book Overviews

Steve Gregg provides comprehensive overviews of books in the Old and New Testaments, highlighting key themes, messages, and prophesies while exploring

Revelation

In this 19-part series, Steve Gregg offers a verse-by-verse analysis of the book of Revelation, discussing topics such as heavenly worship, the renewa

When Shall These Things Be?

In this 14-part series, Steve Gregg challenges commonly held beliefs within Evangelical Church on eschatology topics like the rapture, millennium, and

Deuteronomy

Steve Gregg provides a comprehensive and insightful commentary on the book of Deuteronomy, discussing the Israelites' relationship with God, the impor

Ecclesiastes

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the book of Ecclesiastes, exploring its themes of mortality, the emptiness of worldly pursuits, and the imp

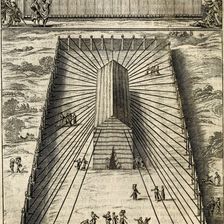

The Tabernacle

"The Tabernacle" is a comprehensive ten-part series that explores the symbolism and significance of the garments worn by priests, the construction and

More on OpenTheo

Protestants and Catholics: What’s the Difference? With Chad Van Dixhoorn, Blair Smith, and Mark McDowell

Life and Books and Everything

November 26, 2025

How should Protestants think about the Catholic Mass? About the Eucharist? About the history and development of the papacy? In this panel discussion,

How Do You Justify Calling Jesus the Messiah?

#STRask

December 18, 2025

Questions about how one can justify calling Jesus the Messiah when he didn’t fulfill the Hebrew messianic prophecies, and whether the reason for the v

Lora Ries: Border Security and Immigration Policy

Knight & Rose Show

December 7, 2025

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose welcome Lora Ries to discuss border security and immigration policy. They explore Biden's policy changes, like ending R

Did God Create Us So He Wouldn’t Be Alone?

#STRask

November 3, 2025

Questions about whether God created us so he wouldn’t be alone, what he had before us, and a comparison between the Muslim view of God and the Christi

The Making of the American Mind with Matthew Spalding

Life and Books and Everything

February 2, 2026

The United States is unique in how much attention it pays to its founding, its founders, and its founding documents. Arguably, the most famous and mos

What About Those Who Never Heard the Name of Jesus?

#STRask

December 22, 2025

Questions about what will happen to those who never heard of Jesus or were brought up in a different faith, whether there’s biblical warrant to think

Are Demon Possessions and Exorcisms in the New Testament Literal?

#STRask

December 11, 2025

Questions about whether references to demon possessions and exorcisms in the New Testament are literal, how to talk to young children about ghosts, an

Can Two Logical People Come to Conflicting Conclusions Without Committing a Fallacy?

#STRask

January 8, 2026

Questions about whether two logical people can come to conflicting conclusions on a topic without committing a fallacy, how Greg, as a public figure,

The Man on the Middle Cross with Alistair Begg

Life and Books and Everything

November 10, 2025

If you haven’t seen the viral clip, go see it right now. In this episode, Kevin talks to Alistair about the preaching clip he didn’t intend to give, h

Christmas Cranks and Christmas Blessings with Justin Taylor and Collin Hansen

Life and Books and Everything

December 17, 2025

If you are looking for a podcast where three friends talk about whatever they want to talk about and ramble on about sports, books, and grievances, th

Why Should We Pray If God Already Knows What’s Going to Happen?

#STRask

January 29, 2026

Questions about why we should pray if God already knows what’s going to happen, how the effectiveness of prayer is measured, and whether or not things

Is It Possible There’s a Being That’s Greater Than God?

#STRask

February 5, 2026

Questions about whether it’s possible there’s a being that’s greater than God and that’s outside of God’s comprehension and omniscience, and how to ex

How Would You Convince Someone That Evil Exists?

#STRask

November 17, 2025

Questions about how to convince someone that evil exists, whether Charlie Kirk’s murder was part of God’s plan, whether that would mean the murderer d

Kingdom Priorities: Following the Teachings of Jesus

Knight & Rose Show

February 14, 2026

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose discuss Jesus' teachings from the Gospels, emphasizing truth, evidence, self-denial, and forgiveness. They explore pass

The Resurrection Standoff: Licona vs. Ehrman on the Unbelievable Podcast

Risen Jesus

October 22, 2025

This episode is taken from the Unbelievable podcast with Justin Brierly in 2011 when Dr. Bart Ehrman and Dr. Michael Licona address the question: Is t