The Canon of Scripture

Church HistorySteve Gregg

Steve Gregg provides insights into the formation of the New Testament and the Canon of Scripture. He argues that none of the books of the Bible were lost and that the Catholic Church did not change the Bible but rather excised irrelevant stuff during the Middle Ages. Furthermore, the Canon was not a product of a decision-making body but had already been recognized and accepted by the early Church. Gregg emphasizes the importance of understanding the historical context of the writings in the New Testament and recognizing which ones were written by apostles and which ones were disputed.

More from Church History

7 of 30

Next in this series

Early Theologians

Church History

Steve Gregg discusses the rise of monasticism and the emergence of the earliest Christian theologians in the second to fourth centuries. He explains t

8 of 30

Romes Truce with the Church

Church History

In this talk, Steve Gregg discusses Rome's relationship with the Church during different periods in history, beginning with the persecution of Christi

5 of 30

Early Heresies

Church History

Steve Gregg discusses early Christian heresies in this talk. He explains that some people defected from the faith, and contemporary apostles who lived

Series by Steve Gregg

Philippians

In this 2-part series, Steve Gregg explores the book of Philippians, encouraging listeners to find true righteousness in Christ rather than relying on

Obadiah

Steve Gregg provides a thorough examination of the book of Obadiah, exploring the conflict between Israel and Edom and how it relates to divine judgem

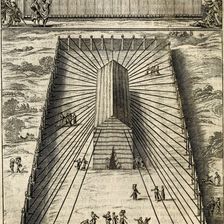

The Tabernacle

"The Tabernacle" is a comprehensive ten-part series that explores the symbolism and significance of the garments worn by priests, the construction and

God's Sovereignty and Man's Salvation

Steve Gregg explores the theological concepts of God's sovereignty and man's salvation, discussing topics such as unconditional election, limited aton

The Life and Teachings of Christ

This 180-part series by Steve Gregg delves into the life and teachings of Christ, exploring topics such as prayer, humility, resurrection appearances,

2 Peter

This series features Steve Gregg teaching verse by verse through the book of 2 Peter, exploring topics such as false prophets, the importance of godli

Hosea

In Steve Gregg's 3-part series on Hosea, he explores the prophetic messages of restored Israel and the coming Messiah, emphasizing themes of repentanc

Church History

Steve Gregg gives a comprehensive overview of church history from the time of the Apostles to the modern day, covering important figures, events, move

Charisma and Character

In this 16-part series, Steve Gregg discusses various gifts of the Spirit, including prophecy, joy, peace, and humility, and emphasizes the importance

Ephesians

In this 10-part series, Steve Gregg provides verse by verse teachings and insights through the book of Ephesians, emphasizing themes such as submissio

More on OpenTheo

The Making of the American Mind with Matthew Spalding

Life and Books and Everything

February 2, 2026

The United States is unique in how much attention it pays to its founding, its founders, and its founding documents. Arguably, the most famous and mos

Prove to Me That Jesus Is Not a Created Being

#STRask

January 26, 2026

Questions about why we should think Jesus is not a created being, and what it means to say God became fully human if part of being human means not bei

Why Would Any Rational Person Have to Use Any Religious Book?

#STRask

December 8, 2025

Questions about why any rational person would have to use any religious book, whether apologetics would be redundant if there were actually a good, un

When I Can’t Stop Thinking About Something, Is That God Speaking?

#STRask

December 1, 2025

Questions about whether having a recurring thought is an indication God is speaking to you, what to say to someone who says they sinned because “God t

Why Does the Bible Teach You How to Be a Proper Slave Owner?

#STRask

November 13, 2025

Question about why it seems like the Bible teaches you how to be a proper slave owner rather than than saying, “Stop it. Give them freedom.”

* It s

How Do We Advocate for Christian Policy Without Making the Government Interfere in Every Area of Life?

#STRask

November 20, 2025

Questions about how to advocate for Christian policy without making the government interfere in every area of life, and the differences between the mo

What Is Wrong with Wokeness? With Neil Shenvi

Life and Books and Everything

January 19, 2026

In this timely interview, Kevin talks to Neil Shenvi about his new book (co-authored with Pat Sawyer), entitled “Post Woke: Asserting a Biblical Visio

Can You Recommend Good Books with More In-Depth Information and Ideas?

#STRask

January 22, 2026

Questions about good books on Christian apologetics, philosophy, and theology with more in-depth information and ideas, and resources to help an intel

How Would You Convince Someone That Evil Exists?

#STRask

November 17, 2025

Questions about how to convince someone that evil exists, whether Charlie Kirk’s murder was part of God’s plan, whether that would mean the murderer d

Are Demon Possessions and Exorcisms in the New Testament Literal?

#STRask

December 11, 2025

Questions about whether references to demon possessions and exorcisms in the New Testament are literal, how to talk to young children about ghosts, an

Can Two Logical People Come to Conflicting Conclusions Without Committing a Fallacy?

#STRask

January 8, 2026

Questions about whether two logical people can come to conflicting conclusions on a topic without committing a fallacy, how Greg, as a public figure,

Is Greg Placing His Faith in the Wrong Thing?

#STRask

February 12, 2026

Questions about Greg placing his faith in his personal assessment of which truth claims best match reality rather than in the revelation of God in Jes

Can You Provide Verifiable, Non-Religious Evidence That a Supernatural Jesus Existed?

#STRask

November 10, 2025

Question about providing verifiable, non-religious evidence that a supernatural Jesus existed.

* I am an atheist and militantly anti-god-belief. Ho

The Resurrection Standoff: Licona vs. Ehrman on the Unbelievable Podcast

Risen Jesus

October 22, 2025

This episode is taken from the Unbelievable podcast with Justin Brierly in 2011 when Dr. Bart Ehrman and Dr. Michael Licona address the question: Is t

E. Calvin Beisner: Climate and Energy Policy

Knight & Rose Show

January 4, 2026

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose welcome Dr. E. Calvin Beisner to discuss climate and energy policy. They explore Biblical dominion and stewardship, con