Job Introduction (Part 1)

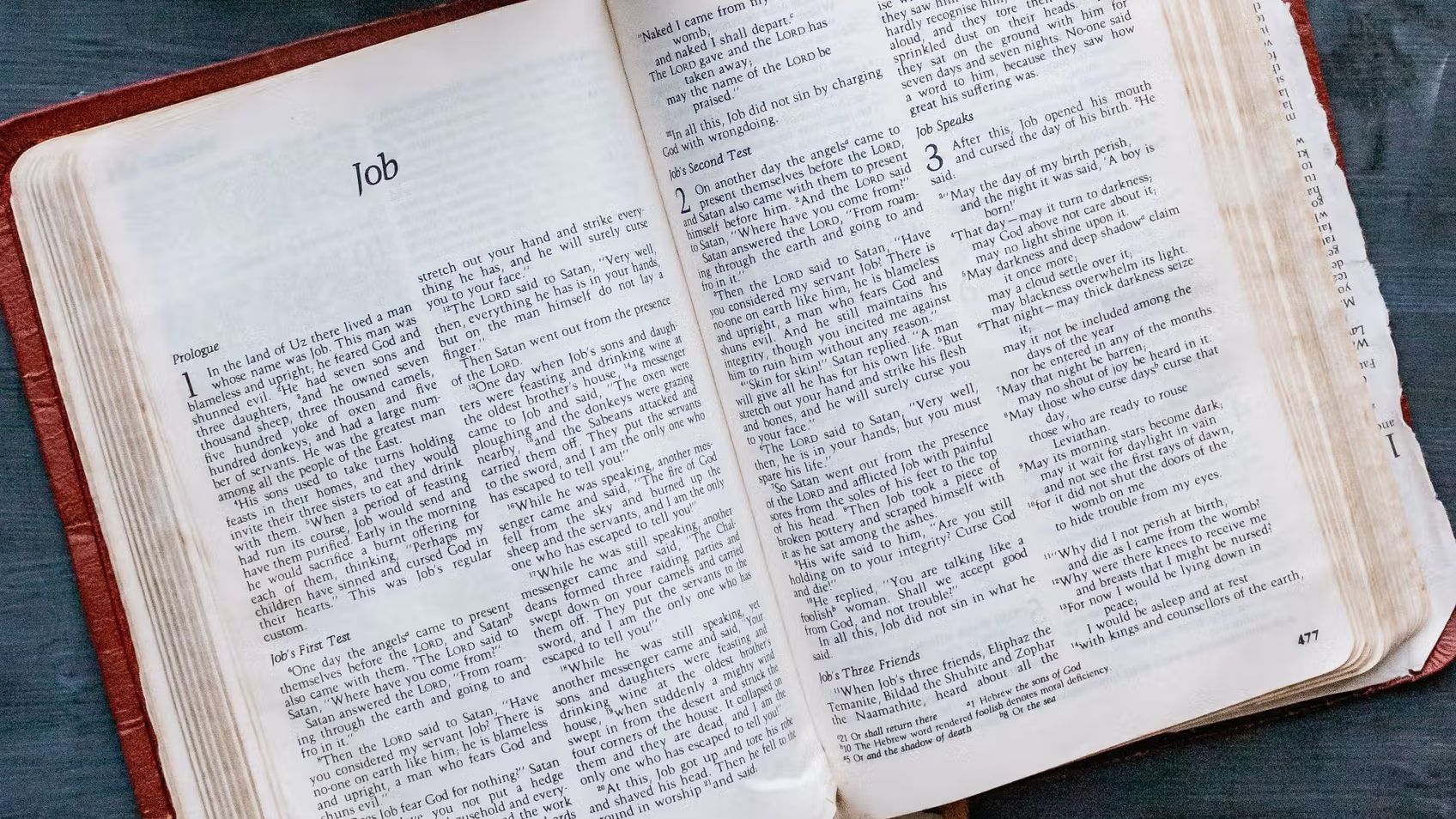

JobSteve Gregg

In this talk, Steve Gregg shares his experience teaching the book of Job and how it can be a difficult read for many people. He discusses the different types of literature found in the Bible, including wisdom literature like Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and Song of Solomon. He also explores the idea that suffering can make one feel less alone and discusses the historical context of Job as a figure possibly living around 2000 BC.

More from Job

2 of 11

Next in this series

Job Introduction (Part 2)

Job

In this second part of the introduction to the book of Job by Steve Gregg, he explores the question of why innocent people suffer. Gregg argues that t

3 of 11

Job 1 - 2

Job

In "Job 1-2", Steve Gregg provides an in-depth analysis of the first two chapters of the Book of Job. He discusses the irony behind Job's counselor ac

Series by Steve Gregg

Amos

In this two-part series, Steve Gregg provides verse-by-verse teachings on the book of Amos, discussing themes such as impending punishment for Israel'

Joshua

Steve Gregg's 13-part series on the book of Joshua provides insightful analysis and application of key themes including spiritual warfare, obedience t

Spiritual Warfare

In "Spiritual Warfare," Steve Gregg explores the tactics of the devil, the methods to resist Satan's devices, the concept of demonic possession, and t

Esther

In this two-part series, Steve Gregg teaches through the book of Esther, discussing its historical significance and the story of Queen Esther's braver

Titus

In this four-part series from Steve Gregg, listeners are taken on an insightful journey through the book of Titus, exploring issues such as good works

Isaiah

A thorough analysis of the book of Isaiah by Steve Gregg, covering various themes like prophecy, eschatology, and the servant songs, providing insight

Nehemiah

A comprehensive analysis by Steve Gregg on the book of Nehemiah, exploring the story of an ordinary man's determination and resilience in rebuilding t

Job

In this 11-part series, Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the book of Job, discussing topics such as suffering, wisdom, and God's role in hum

Beyond End Times

In "Beyond End Times", Steve Gregg discusses the return of Christ, judgement and rewards, and the eternal state of the saved and the lost.

What Are We to Make of Israel

Steve Gregg explores the intricate implications of certain biblical passages in relation to the future of Israel, highlighting the historical context,

More on OpenTheo

An Invitation to the 2026 Coram Deo Pastors Conference

Life and Books and Everything

February 18, 2026

"I love being a pastor, and I love pastors, which is why I hope you will consider joining us at the Coram Deo Pastors Conference in 2026." —Kevin DeYo

Is Greg Placing His Faith in the Wrong Thing?

#STRask

February 12, 2026

Questions about Greg placing his faith in his personal assessment of which truth claims best match reality rather than in the revelation of God in Jes

The Resurrection Standoff: Licona vs. Ehrman on the Unbelievable Podcast

Risen Jesus

October 22, 2025

This episode is taken from the Unbelievable podcast with Justin Brierly in 2011 when Dr. Bart Ehrman and Dr. Michael Licona address the question: Is t

How Do I Determine Which Topics at Work Are Worth Commenting On?

#STRask

January 5, 2026

Questions about how to determine which topics at work are worth commenting on, and a good way to respond when you’re in a group Bible study and hear e

Does God Hear the Prayers of Non-Believers?

#STRask

February 26, 2026

Questions about whether or not God hears and answers the prayers of non-believers, and thoughts about a church sign that reads (as if from God), “Just

Prove to Me That Jesus Is Not a Created Being

#STRask

January 26, 2026

Questions about why we should think Jesus is not a created being, and what it means to say God became fully human if part of being human means not bei

What Is Wrong with Wokeness? With Neil Shenvi

Life and Books and Everything

January 19, 2026

In this timely interview, Kevin talks to Neil Shenvi about his new book (co-authored with Pat Sawyer), entitled “Post Woke: Asserting a Biblical Visio

Is 1 Corinthians 12:3 a Black-and-White Tool for Discernment?

#STRask

October 27, 2025

Questions about whether the claim in 1 Corinthians that “no one can say ‘Jesus is Lord’ except in the Holy Spirit” is a black-and-white tool for disce

Did Jesus Prove He Wasn’t Sinless When He Overturned the Tables?

#STRask

December 29, 2025

Questions about whether Jesus proved he wasn’t sinless when he overturned the tables, whether Jesus’ response to the Pharisees in Mark 3:22–26 was a b

Shouldn’t I Be Praying for My Soul Rather Than for Material Things?

#STRask

February 2, 2026

Questions about whether we should be praying for our souls rather than for material things, why we need to pray about decisions, whether the devil can

Why Is It Necessary to Believe Jesus Is God?

#STRask

February 19, 2026

Questions about why it’s necessary to believe Jesus is God, whether belief in the Trinity is required for salvation, and why one has to believe in the

Protestants and Catholics: What’s the Difference? With Chad Van Dixhoorn, Blair Smith, and Mark McDowell

Life and Books and Everything

November 26, 2025

How should Protestants think about the Catholic Mass? About the Eucharist? About the history and development of the papacy? In this panel discussion,

Did God Create Us So He Wouldn’t Be Alone?

#STRask

November 3, 2025

Questions about whether God created us so he wouldn’t be alone, what he had before us, and a comparison between the Muslim view of God and the Christi

The Making of the American Mind with Matthew Spalding

Life and Books and Everything

February 2, 2026

The United States is unique in how much attention it pays to its founding, its founders, and its founding documents. Arguably, the most famous and mos

How Do We Advocate for Christian Policy Without Making the Government Interfere in Every Area of Life?

#STRask

November 20, 2025

Questions about how to advocate for Christian policy without making the government interfere in every area of life, and the differences between the mo