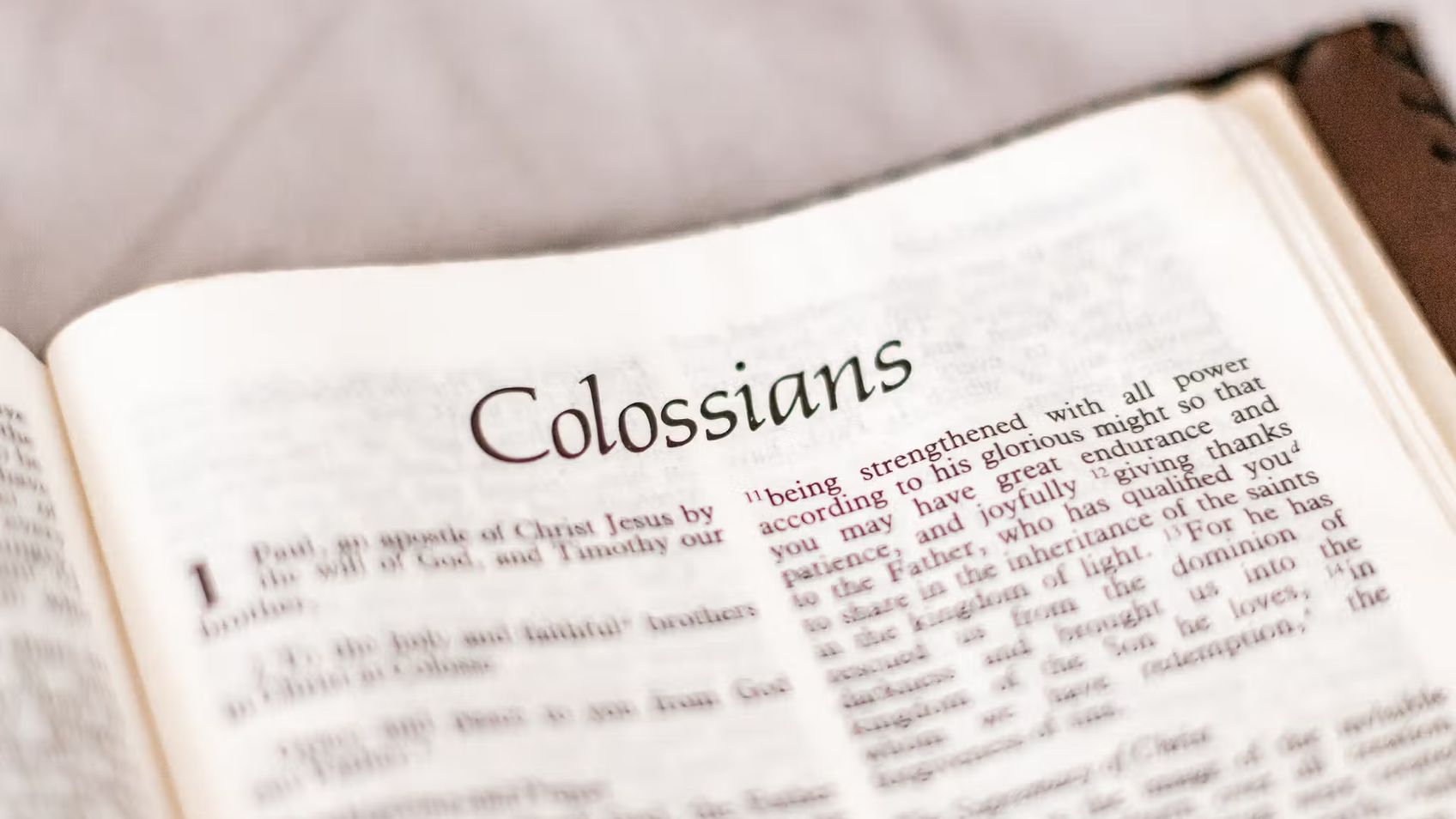

Colossians 1:15 - 1:20

ColossiansSteve Gregg

Steve Gregg delves into the book of Colossians, suggesting that Paul may be quoting an early creedal statement in verses 15-16 and the first part of verse 17. He discusses Jesus' relationship with creation, emphasizing his role as the firstborn and ruler, rather than being eternally begotten. Gregg explores the concept of the church as the body of Christ, highlighting the interconnectedness and shared life of its members. Additionally, he touches on the Greek word "plērōma" used in Colossians, which holds significance in the context of Gnostic sects.

More from Colossians

4 of 8

Next in this series

Colossians 1:21 - 1:29

Colossians

Steve Gregg explores the theme of reconciliation in Colossians 1:21-29. He delves into the concept of God's desire to restore broken relationships and

5 of 8

Colossians 2

Colossians

Steve Gregg offers insights on the book of Colossians, highlighting the complex concept of Christ indwelling believers and the need for a full underst

2 of 8

Colossians 1:5 - 1:15

Colossians

Discover the powerful message of hope and faith found in Colossians 1:5-1:15 as Steve Gregg unpacks the biblical verses. In this in-depth study, Gregg

Series by Steve Gregg

Ten Commandments

Steve Gregg delivers a thought-provoking and insightful lecture series on the relevance and importance of the Ten Commandments in modern times, delvin

Habakkuk

In his series "Habakkuk," Steve Gregg delves into the biblical book of Habakkuk, addressing the prophet's questions about God's actions during a troub

Job

In this 11-part series, Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the book of Job, discussing topics such as suffering, wisdom, and God's role in hum

Ecclesiastes

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the book of Ecclesiastes, exploring its themes of mortality, the emptiness of worldly pursuits, and the imp

Hosea

In Steve Gregg's 3-part series on Hosea, he explores the prophetic messages of restored Israel and the coming Messiah, emphasizing themes of repentanc

The Holy Spirit

Steve Gregg's series "The Holy Spirit" explores the concept of the Holy Spirit and its implications for the Christian life, emphasizing genuine spirit

Sermon on the Mount

Steve Gregg's 14-part series on the Sermon on the Mount deepens the listener's understanding of the Beatitudes and other teachings in Matthew 5-7, emp

Ezra

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the book of Ezra, providing historical context, insights, and commentary on the challenges faced by the Jew

Joel

Steve Gregg provides a thought-provoking analysis of the book of Joel, exploring themes of judgment, restoration, and the role of the Holy Spirit.

What You Absolutely Need To Know Before You Get Married

Steve Gregg's lecture series on marriage emphasizes the gravity of the covenant between two individuals and the importance of understanding God's defi

More on OpenTheo

Why Do We Say Someone Was Saved on a Particular Date If It Was Part of an Eternal Plan?

#STRask

November 24, 2025

Questions about why we say someone was saved on a particular date if it was part of an eternal plan, the Roman Catholic view of the gospel vs. the Bib

Protestants and Catholics: What’s the Difference? With Chad Van Dixhoorn, Blair Smith, and Mark McDowell

Life and Books and Everything

November 26, 2025

How should Protestants think about the Catholic Mass? About the Eucharist? About the history and development of the papacy? In this panel discussion,

Why Should We Pray If God Already Knows What’s Going to Happen?

#STRask

January 29, 2026

Questions about why we should pray if God already knows what’s going to happen, how the effectiveness of prayer is measured, and whether or not things

Conservatism and Religious Freedom with John Wilsey

Life and Books and Everything

October 27, 2025

What is conservatism? And why does it go hand in hand with religious freedom? How should we think about the American experiment of ordered liberty? Ha

Does God Really Need a “Pound of Flesh” to Forgive Sins?

#STRask

January 12, 2026

Questions about how to answer the challenge that God doesn’t need a “pound of flesh” to forgive sins but can simply forgive, and whether the claim in

The Heidelberg Catechism with R. Scott Clark

Life and Books and Everything

November 3, 2025

You may not think you need 1,000 pages on the Heidelberg Catechism, but you do! R. Scott Clark, professor at Westminster Seminary California, has writ

Does God Hear the Prayers of Non-Believers?

#STRask

February 26, 2026

Questions about whether or not God hears and answers the prayers of non-believers, and thoughts about a church sign that reads (as if from God), “Just

An Invitation to the 2026 Coram Deo Pastors Conference

Life and Books and Everything

February 18, 2026

"I love being a pastor, and I love pastors, which is why I hope you will consider joining us at the Coram Deo Pastors Conference in 2026." —Kevin DeYo

Why Would Any Rational Person Have to Use Any Religious Book?

#STRask

December 8, 2025

Questions about why any rational person would have to use any religious book, whether apologetics would be redundant if there were actually a good, un

How Do We Advocate for Christian Policy Without Making the Government Interfere in Every Area of Life?

#STRask

November 20, 2025

Questions about how to advocate for Christian policy without making the government interfere in every area of life, and the differences between the mo

What Do You Think About Churches Advertising on Social Media?

#STRask

January 19, 2026

Questions about whether there’s an issue with churches advertising on social media, whether it’s weird if we pray along with a YouTuber, and whether C

How Would You Convince Someone That Evil Exists?

#STRask

November 17, 2025

Questions about how to convince someone that evil exists, whether Charlie Kirk’s murder was part of God’s plan, whether that would mean the murderer d

Why Does the Bible Teach You How to Be a Proper Slave Owner?

#STRask

November 13, 2025

Question about why it seems like the Bible teaches you how to be a proper slave owner rather than than saying, “Stop it. Give them freedom.”

* It s

What Is Wrong with Wokeness? With Neil Shenvi

Life and Books and Everything

January 19, 2026

In this timely interview, Kevin talks to Neil Shenvi about his new book (co-authored with Pat Sawyer), entitled “Post Woke: Asserting a Biblical Visio

The Making of the American Mind with Matthew Spalding

Life and Books and Everything

February 2, 2026

The United States is unique in how much attention it pays to its founding, its founders, and its founding documents. Arguably, the most famous and mos