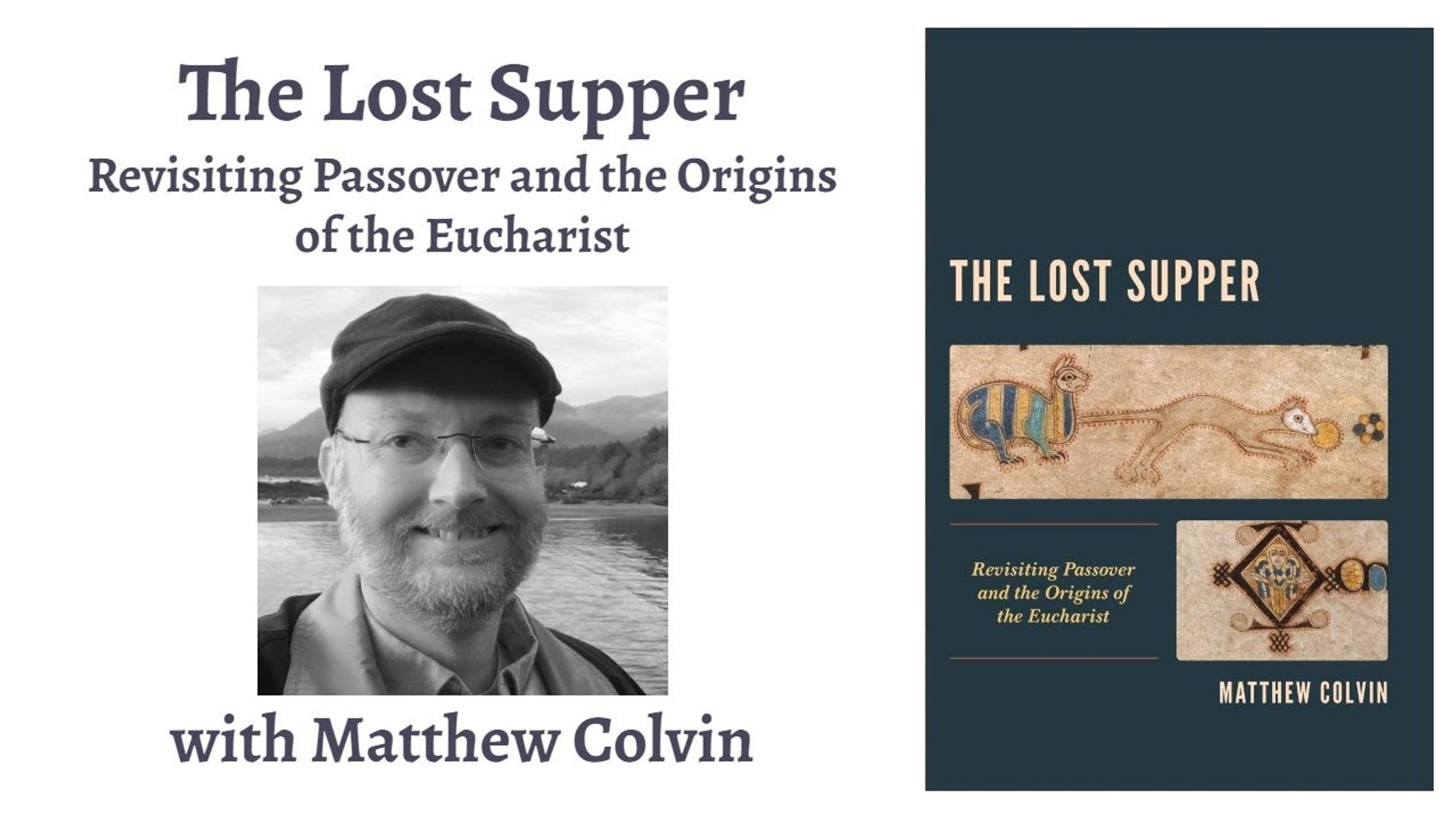

'The Lost Supper' with Matthew Colvin

November 30, 2020

Alastair Roberts

Matthew Colvin joins me to discuss his recent book, 'The Lost Supper' (https://amzn.to/33s5Th0). Within a wide-ranging conversation we discuss the value of rabbinic and other extra-biblical Jewish sources for our reading of the New Testament, the meaning of Christ's words of institution, rethinking the metaphysics and the mechanics of the Supper, Eucharistic practices, and much else besides!

More From Alastair Roberts

December 1st: Psalm 78:41-72 & Acts 24:1-23

Alastair Roberts

November 30, 2020

Learning from the destruction of Shiloh. Paul before Felix.

Reflections upon the readings from the ACNA Book of Common Prayer (http://bcp2019.anglica

December 2nd: Psalm 81 & Acts 24:24—25:12

Alastair Roberts

December 1, 2020

A festal rebuke. Festus becomes governor.

Reflections upon the readings from the ACNA Book of Common Prayer (http://bcp2019.anglicanchurch.net/).

If

December 3rd: Psalm 84 & Acts 25:13-27

Alastair Roberts

December 2, 2020

Longing for the courts of the Lord. Agrippa and Bernice visit Festus.

Reflections upon the readings from the ACNA Book of Common Prayer (http://bcp20

November 30th: Psalm 78:1-18 & John 1:35-42

Alastair Roberts

November 29, 2020

Recounting God's deeds of deliverance. The calling of Andrew and Peter.

Reflections upon the readings from the ACNA Book of Common Prayer (http://bcp

November 29th: Psalms 75 & 76 & Acts 23:12-35

Alastair Roberts

November 28, 2020

The God who executes judgment. A plot against Paul.

Reflections upon the readings from the ACNA Book of Common Prayer (http://bcp2019.anglicanchurch.

November 28th: Psalm 74 & Acts 22:23—23:11

Alastair Roberts

November 27, 2020

A psalm in national disaster. Paul before the Sanhedrin.

Reflections upon the readings from the ACNA Book of Common Prayer (http://bcp2019.anglicanch

More on OpenTheo

How Does It Affect You If a Gay Couple Gets Married or a Woman Has an Abortion?

#STRask

October 16, 2025

Questions about how to respond to someone who asks, ”How does it affect you if a gay couple gets married, or a woman makes a decision about her reprod

Did God Create Us So He Wouldn’t Be Alone?

#STRask

November 3, 2025

Questions about whether God created us so he wouldn’t be alone, what he had before us, and a comparison between the Muslim view of God and the Christi

The Making of the American Mind with Matthew Spalding

Life and Books and Everything

February 2, 2026

The United States is unique in how much attention it pays to its founding, its founders, and its founding documents. Arguably, the most famous and mos

How Do I Determine Which Topics at Work Are Worth Commenting On?

#STRask

January 5, 2026

Questions about how to determine which topics at work are worth commenting on, and a good way to respond when you’re in a group Bible study and hear e

How Can We Know Who Is Teaching the Same Gospel Paul Taught?

#STRask

February 16, 2026

Questions about how we can know who is teaching the same gospel Paul taught, and whether or not Jeremiah 1:5 supports the idea that we pre-existed in

Why Should We Pray If God Already Knows What’s Going to Happen?

#STRask

January 29, 2026

Questions about why we should pray if God already knows what’s going to happen, how the effectiveness of prayer is measured, and whether or not things

Is Greg Placing His Faith in the Wrong Thing?

#STRask

February 12, 2026

Questions about Greg placing his faith in his personal assessment of which truth claims best match reality rather than in the revelation of God in Jes

Lora Ries: Border Security and Immigration Policy

Knight & Rose Show

December 7, 2025

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose welcome Lora Ries to discuss border security and immigration policy. They explore Biden's policy changes, like ending R

“Christians Care More About Ideology than People”

#STRask

October 13, 2025

Questions about how to respond to the critique that Christians care more about ideology than people, and whether we have freedom in America because Ch

Does God Really Need a “Pound of Flesh” to Forgive Sins?

#STRask

January 12, 2026

Questions about how to answer the challenge that God doesn’t need a “pound of flesh” to forgive sins but can simply forgive, and whether the claim in

Is It a Sin to Feel Let Down by God?

#STRask

November 6, 2025

Questions about whether it’s a sin to feel let down by God and whether it would be easier to have a personal relationship with a rock than with a God

When I Can’t Stop Thinking About Something, Is That God Speaking?

#STRask

December 1, 2025

Questions about whether having a recurring thought is an indication God is speaking to you, what to say to someone who says they sinned because “God t

The Heidelberg Catechism with R. Scott Clark

Life and Books and Everything

November 3, 2025

You may not think you need 1,000 pages on the Heidelberg Catechism, but you do! R. Scott Clark, professor at Westminster Seminary California, has writ

How Do I Reconcile the Image of God as Judge with His Love, Grace, and Kindness?

#STRask

October 20, 2025

Questions about how to reconcile the image of God as a judge with his love, grace, and kindness, why our sins are considered to be sins against God, a

Can You Provide Verifiable, Non-Religious Evidence That a Supernatural Jesus Existed?

#STRask

November 10, 2025

Question about providing verifiable, non-religious evidence that a supernatural Jesus existed.

* I am an atheist and militantly anti-god-belief. Ho