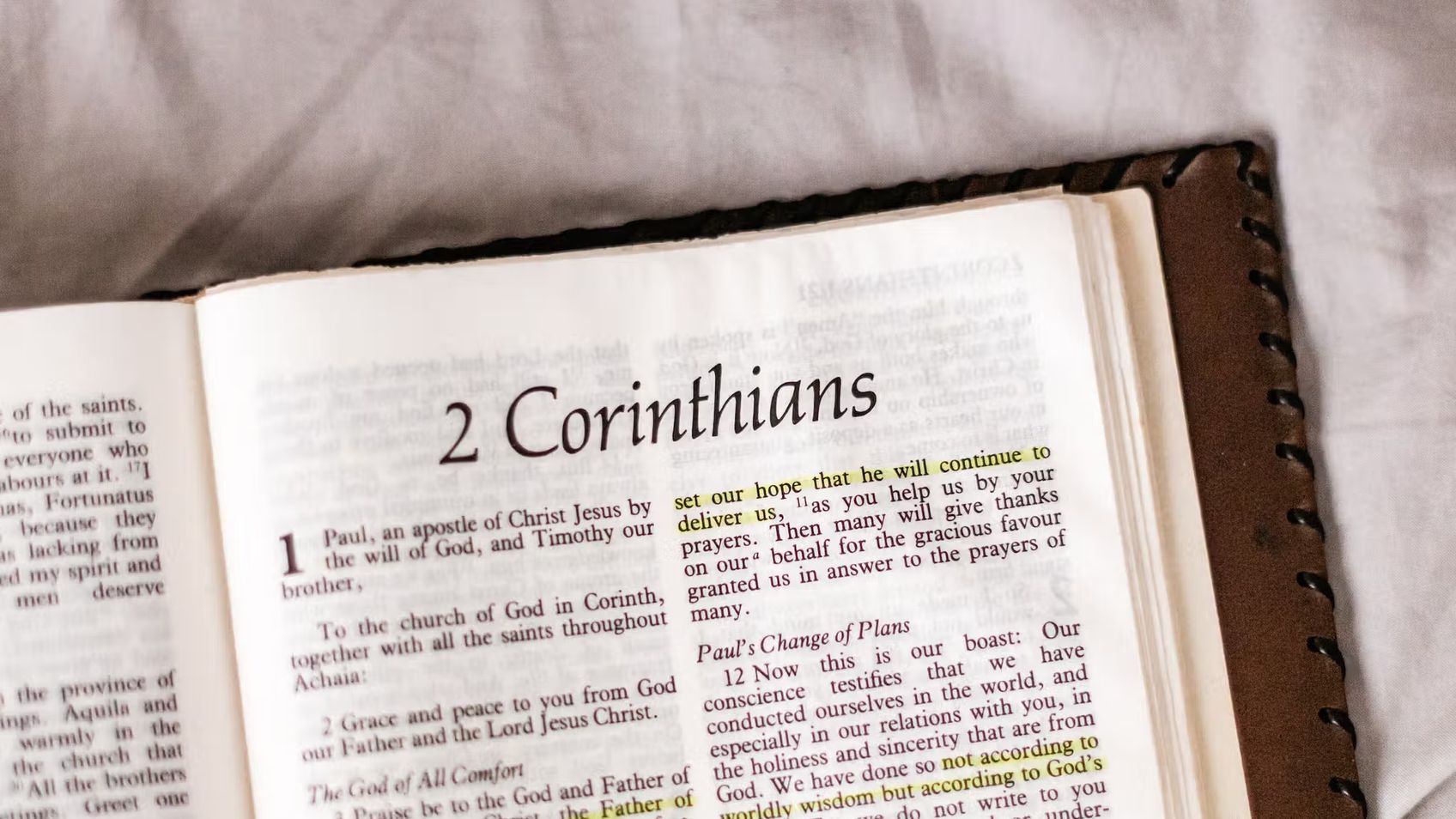

2 Corinthians 5 - 6

2 CorinthiansSteve Gregg

In this talk, Steve Gregg discusses 2 Corinthians 5-6, focusing on the idea of a new creation and our inheritance in Christ. He explores the concept of justification by faith and the meaning of the word "impute," explaining how this relates to our relationship with God. Gregg also touches on the importance of living a righteous life and separating ourselves from worldly influences.

More from 2 Corinthians

7 of 9

Next in this series

2 Corinthians 7 - 9

2 Corinthians

In this talk, Steve Gregg discusses 2 Corinthians 7-9. He emphasizes the exhortation to perfect holiness and the significance of cleansing oneself fro

8 of 9

2 Corinthians 10 - 11

2 Corinthians

Steve Gregg discusses the challenges scholars face in interpreting the last chapters of 2 Corinthians. Scholars believe that the tone and contents of

5 of 9

2 Corinthians 5

2 Corinthians

In this talk, Steve Gregg discusses 2 Corinthians 5 and its implications for eternal destiny. He argues against the concept of perpetual disembodiment

Series by Steve Gregg

Isaiah: A Topical Look At Isaiah

In this 15-part series, Steve Gregg examines the key themes and ideas that recur throughout the book of Isaiah, discussing topics such as the remnant,

Authority of Scriptures

Steve Gregg teaches on the authority of the Scriptures.

The Narrow Path is the radio and internet ministry of Steve Gregg, a servant Bible teacher to

1 Corinthians

Steve Gregg provides a verse-by-verse exposition of 1 Corinthians, delving into themes such as love, spiritual gifts, holiness, and discipline within

Beyond End Times

In "Beyond End Times", Steve Gregg discusses the return of Christ, judgement and rewards, and the eternal state of the saved and the lost.

Obadiah

Steve Gregg provides a thorough examination of the book of Obadiah, exploring the conflict between Israel and Edom and how it relates to divine judgem

Ephesians

In this 10-part series, Steve Gregg provides verse by verse teachings and insights through the book of Ephesians, emphasizing themes such as submissio

Philemon

Steve Gregg teaches a verse-by-verse study of the book of Philemon, examining the historical context and themes, and drawing insights from Paul's pray

Ezra

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the book of Ezra, providing historical context, insights, and commentary on the challenges faced by the Jew

Isaiah

A thorough analysis of the book of Isaiah by Steve Gregg, covering various themes like prophecy, eschatology, and the servant songs, providing insight

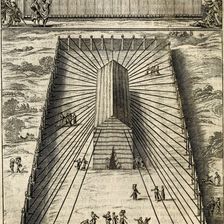

The Tabernacle

"The Tabernacle" is a comprehensive ten-part series that explores the symbolism and significance of the garments worn by priests, the construction and

More on OpenTheo

Why Do We Say Someone Was Saved on a Particular Date If It Was Part of an Eternal Plan?

#STRask

November 24, 2025

Questions about why we say someone was saved on a particular date if it was part of an eternal plan, the Roman Catholic view of the gospel vs. the Bib

Protestants and Catholics: What’s the Difference? With Chad Van Dixhoorn, Blair Smith, and Mark McDowell

Life and Books and Everything

November 26, 2025

How should Protestants think about the Catholic Mass? About the Eucharist? About the history and development of the papacy? In this panel discussion,

Could the Writers of Scripture Have Been Influenced by Their Fallen Nature?

#STRask

October 23, 2025

Questions about whether or not it’s reasonable to worry that some of our current doctrines were influenced by the fallen nature of the apostles, and h

Is 1 Corinthians 12:3 a Black-and-White Tool for Discernment?

#STRask

October 27, 2025

Questions about whether the claim in 1 Corinthians that “no one can say ‘Jesus is Lord’ except in the Holy Spirit” is a black-and-white tool for disce

Is Greg Placing His Faith in the Wrong Thing?

#STRask

February 12, 2026

Questions about Greg placing his faith in his personal assessment of which truth claims best match reality rather than in the revelation of God in Jes

What Do You Think About Churches Advertising on Social Media?

#STRask

January 19, 2026

Questions about whether there’s an issue with churches advertising on social media, whether it’s weird if we pray along with a YouTuber, and whether C

Shouldn’t I Be Praying for My Soul Rather Than for Material Things?

#STRask

February 2, 2026

Questions about whether we should be praying for our souls rather than for material things, why we need to pray about decisions, whether the devil can

Does Open-Mindedness Require Studying Other Religions Before Becoming a Christian?

#STRask

February 9, 2026

Questions about the claim that if Christians really want to be open-minded, they need to read and study other religions before committing to Christian

When I Can’t Stop Thinking About Something, Is That God Speaking?

#STRask

December 1, 2025

Questions about whether having a recurring thought is an indication God is speaking to you, what to say to someone who says they sinned because “God t

How Do You Justify Calling Jesus the Messiah?

#STRask

December 18, 2025

Questions about how one can justify calling Jesus the Messiah when he didn’t fulfill the Hebrew messianic prophecies, and whether the reason for the v

Why Should We Pray If God Already Knows What’s Going to Happen?

#STRask

January 29, 2026

Questions about why we should pray if God already knows what’s going to happen, how the effectiveness of prayer is measured, and whether or not things

An Invitation to the 2026 Coram Deo Pastors Conference

Life and Books and Everything

February 18, 2026

"I love being a pastor, and I love pastors, which is why I hope you will consider joining us at the Coram Deo Pastors Conference in 2026." —Kevin DeYo

How Do I Determine Which Topics at Work Are Worth Commenting On?

#STRask

January 5, 2026

Questions about how to determine which topics at work are worth commenting on, and a good way to respond when you’re in a group Bible study and hear e

How Can I Explain Modesty to My Daughter?

#STRask

November 27, 2025

Questions about how to explain modesty to a nine-year-old in a way that won’t cause shame about her body, and when and how to tell a child about a pre

Conservatism and Religious Freedom with John Wilsey

Life and Books and Everything

October 27, 2025

What is conservatism? And why does it go hand in hand with religious freedom? How should we think about the American experiment of ordered liberty? Ha