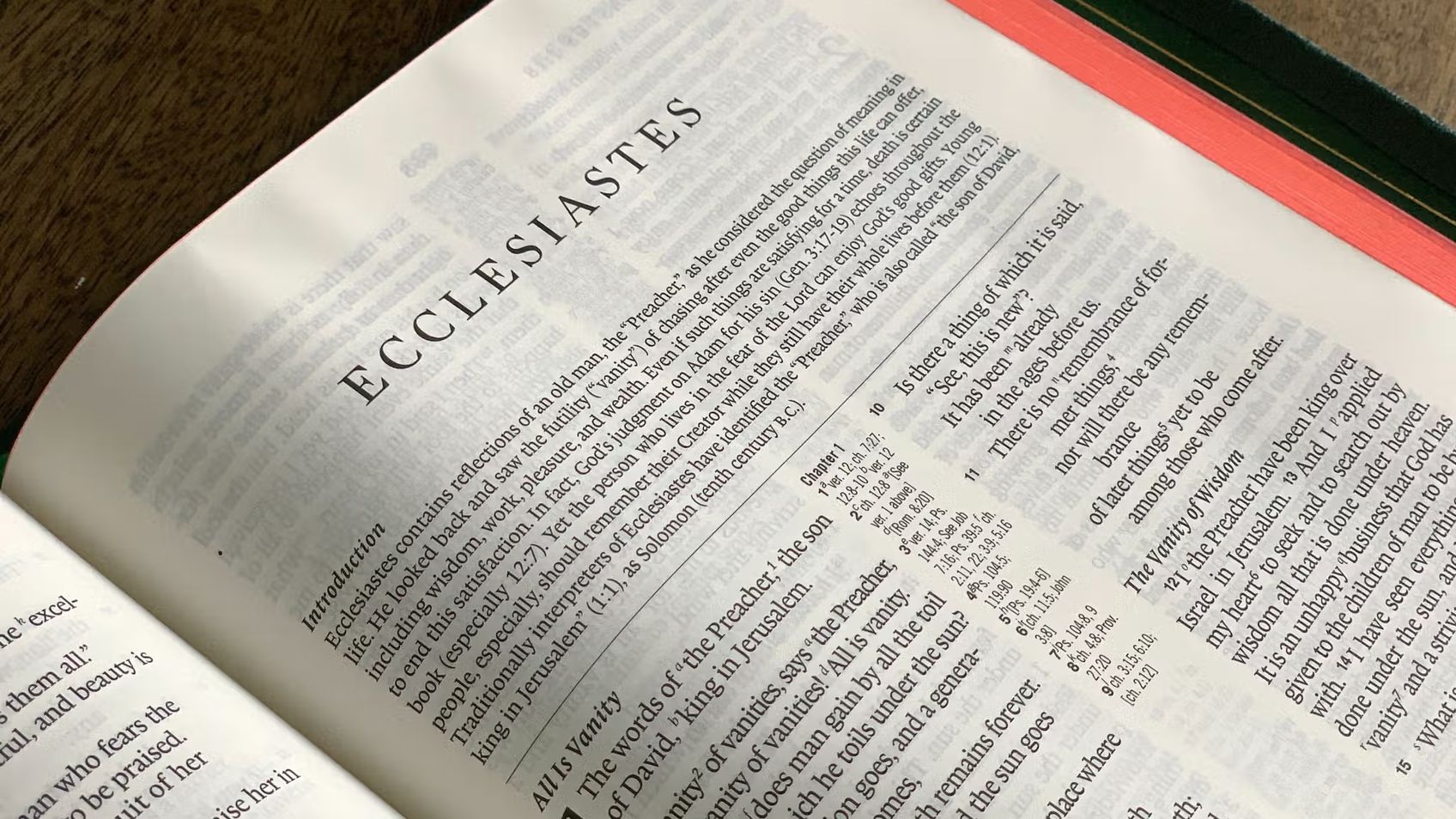

Ecclesiastes Introduction

EcclesiastesSteve Gregg

In this introduction to Ecclesiastes, Steve Gregg explores the origins and meaning of the book. While some believe that King Solomon wrote Ecclesiastes, there are differing opinions on the book's authorship. Nevertheless, the book is generally considered a deeply contemplative work that explores the emptiness and futility of worldly pursuits. Despite its pessimistic tone, Ecclesiastes is a meaningful and thought-provoking book that continues to inspire readers today.

More from Ecclesiastes

2 of 4

Next in this series

Ecclesiastes 1 - 4

Ecclesiastes

In this lecture, Steve Gregg discusses Ecclesiastes 1-4 and its message about the emptiness of worldly pursuits. The author, who identifies himself as

3 of 4

Ecclesiastes 5- 7

Ecclesiastes

In his teachings on Ecclesiastes 5-7, Steve Gregg emphasizes the importance of making reliable and honest commitments, rather than vague or unrealisti

Series by Steve Gregg

3 John

In this series from biblical scholar Steve Gregg, the book of 3 John is examined to illuminate the early developments of church government and leaders

Strategies for Unity

"Strategies for Unity" is a 4-part series discussing the importance of Christian unity, overcoming division, promoting positive relationships, and pri

Three Views of Hell

Steve Gregg discusses the three different views held by Christians about Hell: the traditional view, universalism, and annihilationism. He delves into

Colossians

In this 8-part series from Steve Gregg, listeners are taken on an insightful journey through the book of Colossians, exploring themes of transformatio

Obadiah

Steve Gregg provides a thorough examination of the book of Obadiah, exploring the conflict between Israel and Edom and how it relates to divine judgem

Ruth

Steve Gregg provides insightful analysis on the biblical book of Ruth, exploring its historical context, themes of loyalty and redemption, and the cul

1 Samuel

In this 15-part series, Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the biblical book of 1 Samuel, examining the story of David's journey to becoming k

2 Kings

In this 12-part series, Steve Gregg provides a thorough verse-by-verse analysis of the biblical book 2 Kings, exploring themes of repentance, reform,

What You Absolutely Need To Know Before You Get Married

Steve Gregg's lecture series on marriage emphasizes the gravity of the covenant between two individuals and the importance of understanding God's defi

Jude

Steve Gregg provides a comprehensive analysis of the biblical book of Jude, exploring its themes of faith, perseverance, and the use of apocryphal lit

More on OpenTheo

How Can I Explain Modesty to My Daughter?

#STRask

November 27, 2025

Questions about how to explain modesty to a nine-year-old in a way that won’t cause shame about her body, and when and how to tell a child about a pre

The Resurrection Standoff: Licona vs. Ehrman on the Unbelievable Podcast

Risen Jesus

October 22, 2025

This episode is taken from the Unbelievable podcast with Justin Brierly in 2011 when Dr. Bart Ehrman and Dr. Michael Licona address the question: Is t

E. Calvin Beisner: Climate and Energy Policy

Knight & Rose Show

January 4, 2026

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose welcome Dr. E. Calvin Beisner to discuss climate and energy policy. They explore Biblical dominion and stewardship, con

Prove to Me That Jesus Is Not a Created Being

#STRask

January 26, 2026

Questions about why we should think Jesus is not a created being, and what it means to say God became fully human if part of being human means not bei

Why Would Any Rational Person Have to Use Any Religious Book?

#STRask

December 8, 2025

Questions about why any rational person would have to use any religious book, whether apologetics would be redundant if there were actually a good, un

Does God Really Need a “Pound of Flesh” to Forgive Sins?

#STRask

January 12, 2026

Questions about how to answer the challenge that God doesn’t need a “pound of flesh” to forgive sins but can simply forgive, and whether the claim in

Did Jesus Prove He Wasn’t Sinless When He Overturned the Tables?

#STRask

December 29, 2025

Questions about whether Jesus proved he wasn’t sinless when he overturned the tables, whether Jesus’ response to the Pharisees in Mark 3:22–26 was a b

Why Should We Pray If God Already Knows What’s Going to Happen?

#STRask

January 29, 2026

Questions about why we should pray if God already knows what’s going to happen, how the effectiveness of prayer is measured, and whether or not things

Can You Provide Verifiable, Non-Religious Evidence That a Supernatural Jesus Existed?

#STRask

November 10, 2025

Question about providing verifiable, non-religious evidence that a supernatural Jesus existed.

* I am an atheist and militantly anti-god-belief. Ho

Christmas Cranks and Christmas Blessings with Justin Taylor and Collin Hansen

Life and Books and Everything

December 17, 2025

If you are looking for a podcast where three friends talk about whatever they want to talk about and ramble on about sports, books, and grievances, th

Are Demon Possessions and Exorcisms in the New Testament Literal?

#STRask

December 11, 2025

Questions about whether references to demon possessions and exorcisms in the New Testament are literal, how to talk to young children about ghosts, an

Why Are So Many Christians Condemning LGB People Just Because of How They Love?

#STRask

January 15, 2026

Questions about Christians condemning LGB people just because of how they love, how God can expect someone to be celibate when others are free to marr

Why Does the Bible Teach You How to Be a Proper Slave Owner?

#STRask

November 13, 2025

Question about why it seems like the Bible teaches you how to be a proper slave owner rather than than saying, “Stop it. Give them freedom.”

* It s

Are You Accursed If You Tithe?

#STRask

December 15, 2025

Questions about whether anyone who tithes is not a Christian and is accursed since Paul says that if you obey one part of the Mosaic Law you’re obliga

What Is Wrong with Wokeness? With Neil Shenvi

Life and Books and Everything

January 19, 2026

In this timely interview, Kevin talks to Neil Shenvi about his new book (co-authored with Pat Sawyer), entitled “Post Woke: Asserting a Biblical Visio