Ecclesiastes 1 - 4

EcclesiastesSteve Gregg

In this lecture, Steve Gregg discusses Ecclesiastes 1-4 and its message about the emptiness of worldly pursuits. The author, who identifies himself as the preacher and son of David, sets out to discover if anything in life is not vanity. Unfortunately, his conclusion is that everything is vanity, including knowledge and human pursuits. While the book acknowledges God's existence, it encourages readers to enjoy life, acknowledging that everything will pass away, but God will remain. The lecture ends with Gregg discussing the importance of relationships and the need for individuals to work together to accomplish tasks.

More from Ecclesiastes

3 of 4

Next in this series

Ecclesiastes 5- 7

Ecclesiastes

In his teachings on Ecclesiastes 5-7, Steve Gregg emphasizes the importance of making reliable and honest commitments, rather than vague or unrealisti

4 of 4

Ecclesiastes 8 - 12

Ecclesiastes

In Ecclesiastes 8-12, Steve Gregg examines the themes of mortality, the uncertainty of life, and the importance of seeking God in all aspects of life.

1 of 4

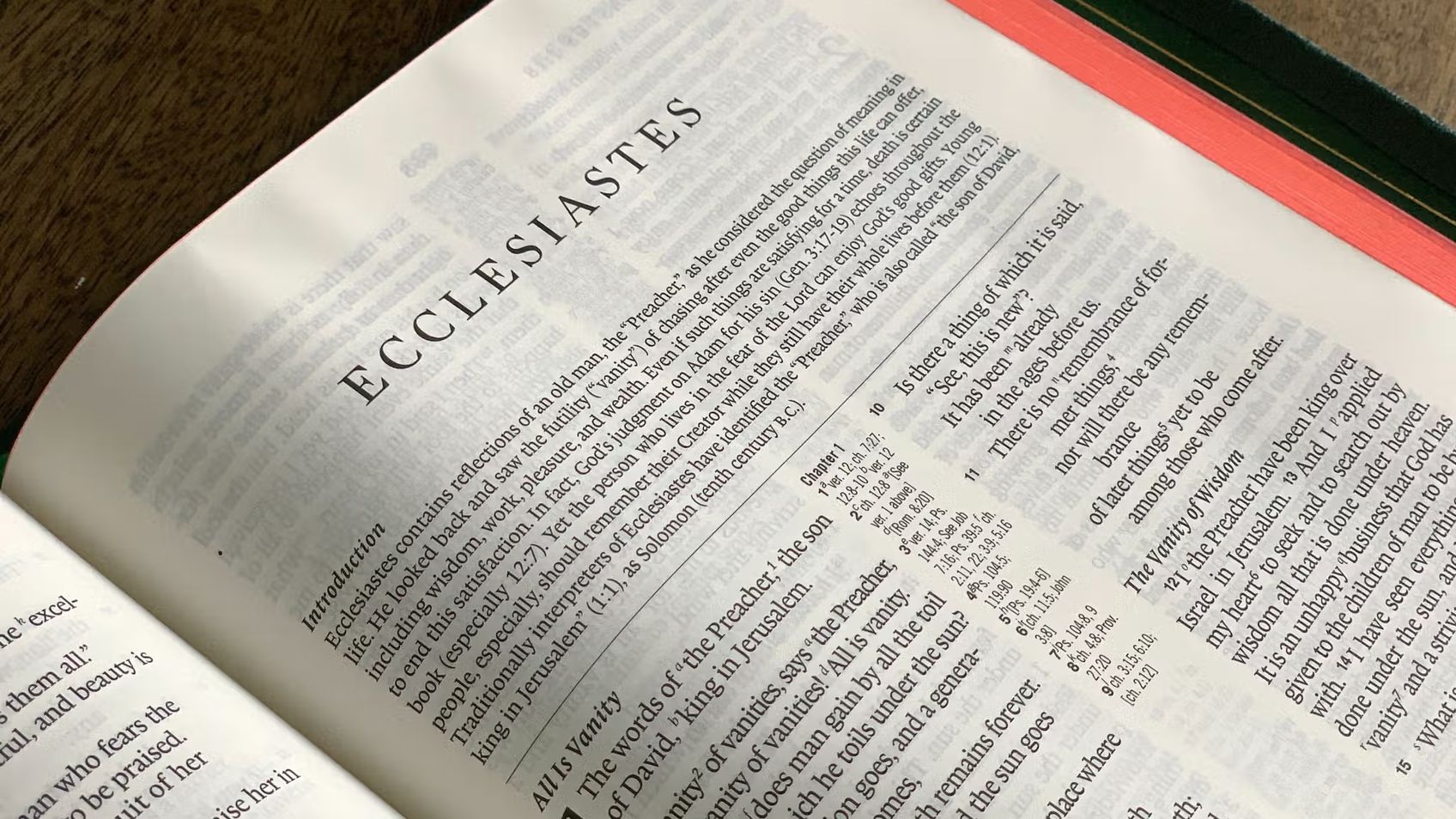

Ecclesiastes Introduction

Ecclesiastes

In this introduction to Ecclesiastes, Steve Gregg explores the origins and meaning of the book. While some believe that King Solomon wrote Ecclesiaste

Series by Steve Gregg

Genesis

Steve Gregg provides a detailed analysis of the book of Genesis in this 40-part series, exploring concepts of Christian discipleship, faith, obedience

Church History

Steve Gregg gives a comprehensive overview of church history from the time of the Apostles to the modern day, covering important figures, events, move

Philippians

In this 2-part series, Steve Gregg explores the book of Philippians, encouraging listeners to find true righteousness in Christ rather than relying on

Foundations of the Christian Faith

This series by Steve Gregg delves into the foundational beliefs of Christianity, including topics such as baptism, faith, repentance, resurrection, an

Joel

Steve Gregg provides a thought-provoking analysis of the book of Joel, exploring themes of judgment, restoration, and the role of the Holy Spirit.

Wisdom Literature

In this four-part series, Steve Gregg explores the wisdom literature of the Bible, emphasizing the importance of godly behavior and understanding the

When Shall These Things Be?

In this 14-part series, Steve Gregg challenges commonly held beliefs within Evangelical Church on eschatology topics like the rapture, millennium, and

Joshua

Steve Gregg's 13-part series on the book of Joshua provides insightful analysis and application of key themes including spiritual warfare, obedience t

God's Sovereignty and Man's Salvation

Steve Gregg explores the theological concepts of God's sovereignty and man's salvation, discussing topics such as unconditional election, limited aton

Beyond End Times

In "Beyond End Times", Steve Gregg discusses the return of Christ, judgement and rewards, and the eternal state of the saved and the lost.

More on OpenTheo

Is It a Sin to Feel Let Down by God?

#STRask

November 6, 2025

Questions about whether it’s a sin to feel let down by God and whether it would be easier to have a personal relationship with a rock than with a God

Did Jesus Prove He Wasn’t Sinless When He Overturned the Tables?

#STRask

December 29, 2025

Questions about whether Jesus proved he wasn’t sinless when he overturned the tables, whether Jesus’ response to the Pharisees in Mark 3:22–26 was a b

How Can We Know Who Is Teaching the Same Gospel Paul Taught?

#STRask

February 16, 2026

Questions about how we can know who is teaching the same gospel Paul taught, and whether or not Jeremiah 1:5 supports the idea that we pre-existed in

Protestants and Catholics: What’s the Difference? With Chad Van Dixhoorn, Blair Smith, and Mark McDowell

Life and Books and Everything

November 26, 2025

How should Protestants think about the Catholic Mass? About the Eucharist? About the history and development of the papacy? In this panel discussion,

Conservatism and Religious Freedom with John Wilsey

Life and Books and Everything

October 27, 2025

What is conservatism? And why does it go hand in hand with religious freedom? How should we think about the American experiment of ordered liberty? Ha

How Do We Advocate for Christian Policy Without Making the Government Interfere in Every Area of Life?

#STRask

November 20, 2025

Questions about how to advocate for Christian policy without making the government interfere in every area of life, and the differences between the mo

What Are Some Good Ways to Start a Conversation About God with Family Members?

#STRask

October 30, 2025

Questions about how to start a conversation about God with non-Christian family members, how to keep from becoming emotional when discussing faith iss

Can Two Logical People Come to Conflicting Conclusions Without Committing a Fallacy?

#STRask

January 8, 2026

Questions about whether two logical people can come to conflicting conclusions on a topic without committing a fallacy, how Greg, as a public figure,

The Heidelberg Catechism with R. Scott Clark

Life and Books and Everything

November 3, 2025

You may not think you need 1,000 pages on the Heidelberg Catechism, but you do! R. Scott Clark, professor at Westminster Seminary California, has writ

What Tools of Reasoning Help You Know What’s True, Right, and Good?

#STRask

December 4, 2025

Question about what tools of reasoning help us determine whether something is true or false, right or wrong, good or bad before bringing Scripture int

Why Is It Necessary to Believe Jesus Is God?

#STRask

February 19, 2026

Questions about why it’s necessary to believe Jesus is God, whether belief in the Trinity is required for salvation, and why one has to believe in the

Are Demon Possessions and Exorcisms in the New Testament Literal?

#STRask

December 11, 2025

Questions about whether references to demon possessions and exorcisms in the New Testament are literal, how to talk to young children about ghosts, an

Why Do We Say Someone Was Saved on a Particular Date If It Was Part of an Eternal Plan?

#STRask

November 24, 2025

Questions about why we say someone was saved on a particular date if it was part of an eternal plan, the Roman Catholic view of the gospel vs. the Bib

Shouldn’t I Be Praying for My Soul Rather Than for Material Things?

#STRask

February 2, 2026

Questions about whether we should be praying for our souls rather than for material things, why we need to pray about decisions, whether the devil can

Lora Ries: Border Security and Immigration Policy

Knight & Rose Show

December 7, 2025

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose welcome Lora Ries to discuss border security and immigration policy. They explore Biden's policy changes, like ending R