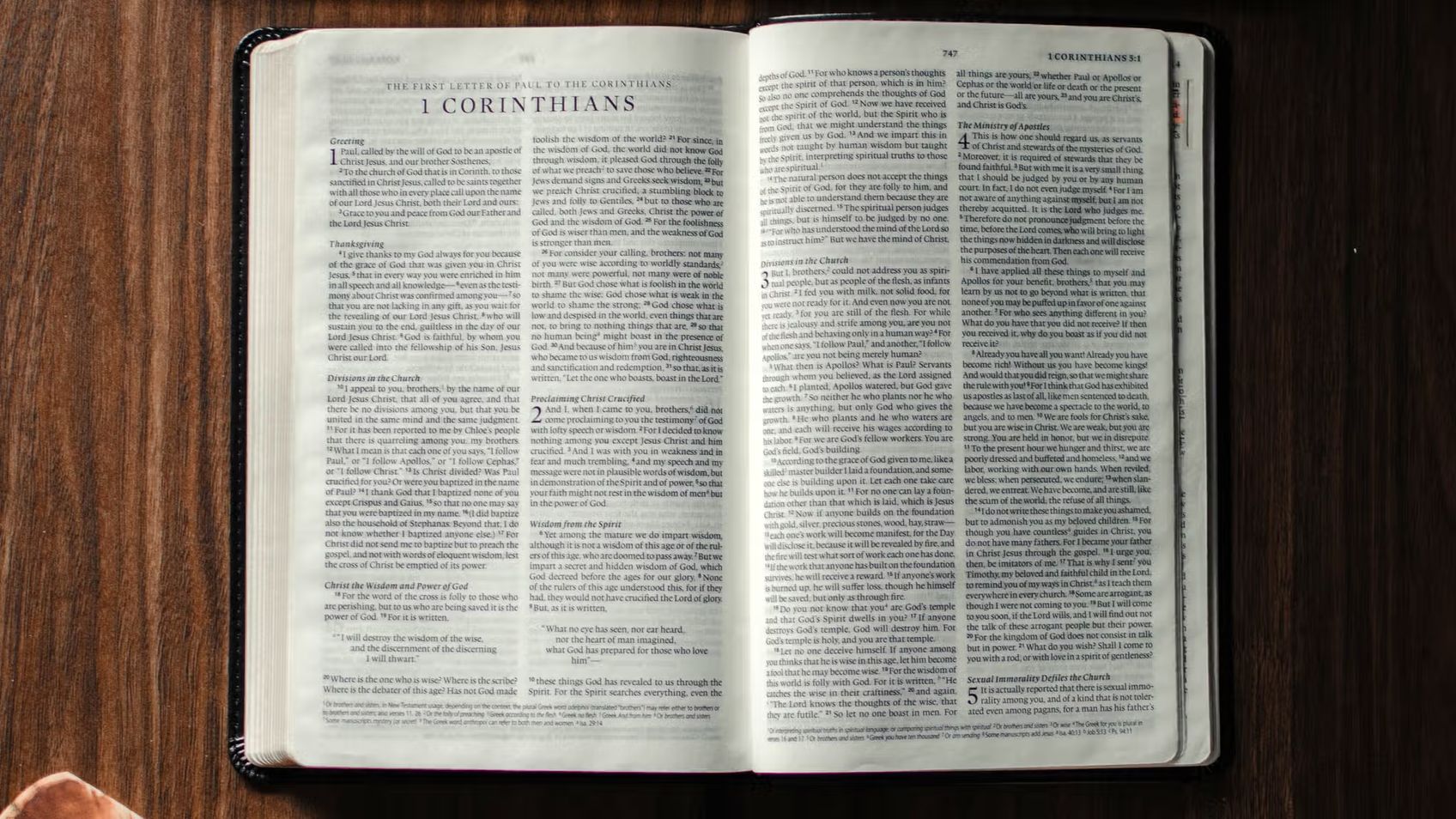

1 Corinthians 1:10-31

1 CorinthiansSteve Gregg

In this discourse on 1 Corinthians 1:10-31, Steve Gregg emphasizes the importance of unity in the church and rebukes the sectarian spirit that leads to denominationalism. He notes that while Christians may have different opinions on peripheral issues, they should aim for unity in the essence of the gospel. Gregg also highlights the superiority of God's wisdom over human wisdom, asserting that without direct revelation from God, man cannot truly know Him. Finally, he emphasizes that faith ultimately rests on the conviction of the Holy Spirit, rather than human reasoning.

More from 1 Corinthians

3 of 17

Next in this series

1 Corinthians 2:1-13

1 Corinthians

In this discussion, Steve Gregg covers 1 Corinthians 2, addressing themes of disunity, church leadership, and the importance of relying on the power o

4 of 17

1 Corinthians 2:14 - 4:7

1 Corinthians

In 1 Corinthians 2:14-4:7, Steve Gregg discusses spiritual discernment and the importance of valuing and revering God's word. He highlights that spiri

1 of 17

1 Corinthians 1:1-9

1 Corinthians

In this commentary on 1 Corinthians 1:1-9, Steve Gregg explores various themes present in the text. The letter written by Paul to the Corinthian churc

Series by Steve Gregg

1 John

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the book of 1 John, providing commentary and insights on topics such as walking in the light and love of Go

Esther

In this two-part series, Steve Gregg teaches through the book of Esther, discussing its historical significance and the story of Queen Esther's braver

Jeremiah

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through a 16-part analysis of the book of Jeremiah, discussing its themes of repentance, faithfulness, and the cons

Evangelism

Evangelism by Steve Gregg is a 6-part series that delves into the essence of evangelism and its role in discipleship, exploring the biblical foundatio

Exodus

Steve Gregg's "Exodus" is a 25-part teaching series that delves into the book of Exodus verse by verse, covering topics such as the Ten Commandments,

How Can I Know That I Am Really Saved?

In this four-part series, Steve Gregg explores the concept of salvation using 1 John as a template and emphasizes the importance of love, faith, godli

Toward a Radically Christian Counterculture

Steve Gregg presents a vision for building a distinctive and holy Christian culture that stands in opposition to the values of the surrounding secular

Colossians

In this 8-part series from Steve Gregg, listeners are taken on an insightful journey through the book of Colossians, exploring themes of transformatio

Gospel of Matthew

Spanning 72 hours of teaching, Steve Gregg's verse by verse teaching through the Gospel of Matthew provides a thorough examination of Jesus' life and

Three Views of Hell

Steve Gregg discusses the three different views held by Christians about Hell: the traditional view, universalism, and annihilationism. He delves into

More on OpenTheo

Life and Ministry in Charlotte and in the SBC with Clint Pressley

Life and Books and Everything

December 15, 2025

In a rare cultural anomaly that may never be repeated in our lifetimes, the current SBC President and current PCA Moderator live in the same neighborh

Can Two Logical People Come to Conflicting Conclusions Without Committing a Fallacy?

#STRask

January 8, 2026

Questions about whether two logical people can come to conflicting conclusions on a topic without committing a fallacy, how Greg, as a public figure,

The Man on the Middle Cross with Alistair Begg

Life and Books and Everything

November 10, 2025

If you haven’t seen the viral clip, go see it right now. In this episode, Kevin talks to Alistair about the preaching clip he didn’t intend to give, h

Why Should We Pray If God Already Knows What’s Going to Happen?

#STRask

January 29, 2026

Questions about why we should pray if God already knows what’s going to happen, how the effectiveness of prayer is measured, and whether or not things

What Is Wrong with Wokeness? With Neil Shenvi

Life and Books and Everything

January 19, 2026

In this timely interview, Kevin talks to Neil Shenvi about his new book (co-authored with Pat Sawyer), entitled “Post Woke: Asserting a Biblical Visio

Kingdom Priorities: Following the Teachings of Jesus

Knight & Rose Show

February 14, 2026

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose discuss Jesus' teachings from the Gospels, emphasizing truth, evidence, self-denial, and forgiveness. They explore pass

Why Would Any Rational Person Have to Use Any Religious Book?

#STRask

December 8, 2025

Questions about why any rational person would have to use any religious book, whether apologetics would be redundant if there were actually a good, un

What Are Some Good Ways to Start a Conversation About God with Family Members?

#STRask

October 30, 2025

Questions about how to start a conversation about God with non-Christian family members, how to keep from becoming emotional when discussing faith iss

Does Open-Mindedness Require Studying Other Religions Before Becoming a Christian?

#STRask

February 9, 2026

Questions about the claim that if Christians really want to be open-minded, they need to read and study other religions before committing to Christian

Does God Really Need a “Pound of Flesh” to Forgive Sins?

#STRask

January 12, 2026

Questions about how to answer the challenge that God doesn’t need a “pound of flesh” to forgive sins but can simply forgive, and whether the claim in

Does God Hear the Prayers of Non-Believers?

#STRask

February 26, 2026

Questions about whether or not God hears and answers the prayers of non-believers, and thoughts about a church sign that reads (as if from God), “Just

An Invitation to the 2026 Coram Deo Pastors Conference

Life and Books and Everything

February 18, 2026

"I love being a pastor, and I love pastors, which is why I hope you will consider joining us at the Coram Deo Pastors Conference in 2026." —Kevin DeYo

How Would You Convince Someone That Evil Exists?

#STRask

November 17, 2025

Questions about how to convince someone that evil exists, whether Charlie Kirk’s murder was part of God’s plan, whether that would mean the murderer d

The Making of the American Mind with Matthew Spalding

Life and Books and Everything

February 2, 2026

The United States is unique in how much attention it pays to its founding, its founders, and its founding documents. Arguably, the most famous and mos

How Can We Know Who Is Teaching the Same Gospel Paul Taught?

#STRask

February 16, 2026

Questions about how we can know who is teaching the same gospel Paul taught, and whether or not Jeremiah 1:5 supports the idea that we pre-existed in