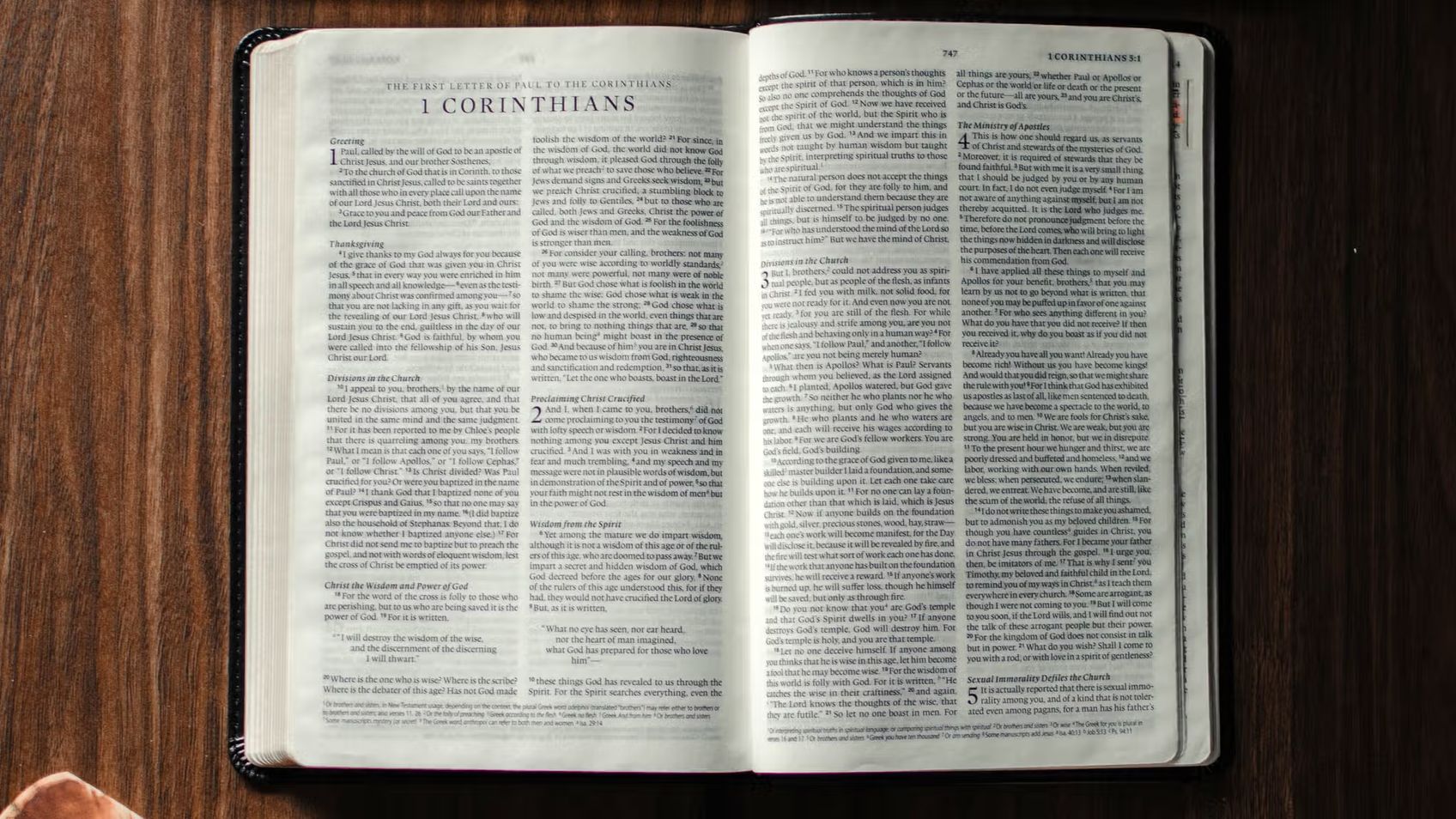

1 Corinthians 2:1-13

1 CorinthiansSteve Gregg

In this discussion, Steve Gregg covers 1 Corinthians 2, addressing themes of disunity, church leadership, and the importance of relying on the power of God over human wisdom. He emphasizes the need to understand spiritual truths and stresses the importance of personal encounters with God's power, which are immune to persuasive arguments against Christianity. Ultimately, Gregg argues that it is a personal experience of encountering the Holy Spirit and a loyal devotion to God that forms the foundation of the Christian faith.

More from 1 Corinthians

4 of 17

Next in this series

1 Corinthians 2:14 - 4:7

1 Corinthians

In 1 Corinthians 2:14-4:7, Steve Gregg discusses spiritual discernment and the importance of valuing and revering God's word. He highlights that spiri

5 of 17

1 Corinthians 4:8-21

1 Corinthians

In 1 Corinthians 4:8-21, Paul addresses the issue of divisiveness and carnal behavior in the church, emphasizing the importance of humility and reject

2 of 17

1 Corinthians 1:10-31

1 Corinthians

In this discourse on 1 Corinthians 1:10-31, Steve Gregg emphasizes the importance of unity in the church and rebukes the sectarian spirit that leads t

Series by Steve Gregg

Jude

Steve Gregg provides a comprehensive analysis of the biblical book of Jude, exploring its themes of faith, perseverance, and the use of apocryphal lit

2 Timothy

In this insightful series on 2 Timothy, Steve Gregg explores the importance of self-control, faith, and sound doctrine in the Christian life, urging b

Ephesians

In this 10-part series, Steve Gregg provides verse by verse teachings and insights through the book of Ephesians, emphasizing themes such as submissio

Joel

Steve Gregg provides a thought-provoking analysis of the book of Joel, exploring themes of judgment, restoration, and the role of the Holy Spirit.

What Are We to Make of Israel

Steve Gregg explores the intricate implications of certain biblical passages in relation to the future of Israel, highlighting the historical context,

2 Corinthians

This series by Steve Gregg is a verse-by-verse study through 2 Corinthians, covering various themes such as new creation, justification, comfort durin

Genuinely Following Jesus

Steve Gregg's lecture series on discipleship emphasizes the importance of following Jesus and becoming more like Him in character and values. He highl

Content of the Gospel

"Content of the Gospel" by Steve Gregg is a comprehensive exploration of the transformative nature of the Gospel, emphasizing the importance of repent

Lamentations

Unveiling the profound grief and consequences of Jerusalem's destruction, Steve Gregg examines the book of Lamentations in a two-part series, delving

Nehemiah

A comprehensive analysis by Steve Gregg on the book of Nehemiah, exploring the story of an ordinary man's determination and resilience in rebuilding t

More on OpenTheo

Is Greg Placing His Faith in the Wrong Thing?

#STRask

February 12, 2026

Questions about Greg placing his faith in his personal assessment of which truth claims best match reality rather than in the revelation of God in Jes

The Man on the Middle Cross with Alistair Begg

Life and Books and Everything

November 10, 2025

If you haven’t seen the viral clip, go see it right now. In this episode, Kevin talks to Alistair about the preaching clip he didn’t intend to give, h

Prove to Me That Jesus Is Not a Created Being

#STRask

January 26, 2026

Questions about why we should think Jesus is not a created being, and what it means to say God became fully human if part of being human means not bei

Sense, Sensibility, and Adam Smith with Jan Van Vliet

Life and Books and Everything

February 16, 2026

This year is a special anniversary for the United States as Americans celebrate 250 years of independence. But 1776 was an important year in more ways

Does Open-Mindedness Require Studying Other Religions Before Becoming a Christian?

#STRask

February 9, 2026

Questions about the claim that if Christians really want to be open-minded, they need to read and study other religions before committing to Christian

What Tools of Reasoning Help You Know What’s True, Right, and Good?

#STRask

December 4, 2025

Question about what tools of reasoning help us determine whether something is true or false, right or wrong, good or bad before bringing Scripture int

Why Do We Say Someone Was Saved on a Particular Date If It Was Part of an Eternal Plan?

#STRask

November 24, 2025

Questions about why we say someone was saved on a particular date if it was part of an eternal plan, the Roman Catholic view of the gospel vs. the Bib

What About Those Who Never Heard the Name of Jesus?

#STRask

December 22, 2025

Questions about what will happen to those who never heard of Jesus or were brought up in a different faith, whether there’s biblical warrant to think

Kingdom Priorities: Following the Teachings of Jesus

Knight & Rose Show

February 14, 2026

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose discuss Jesus' teachings from the Gospels, emphasizing truth, evidence, self-denial, and forgiveness. They explore pass

When I Can’t Stop Thinking About Something, Is That God Speaking?

#STRask

December 1, 2025

Questions about whether having a recurring thought is an indication God is speaking to you, what to say to someone who says they sinned because “God t

Life and Ministry in Charlotte and in the SBC with Clint Pressley

Life and Books and Everything

December 15, 2025

In a rare cultural anomaly that may never be repeated in our lifetimes, the current SBC President and current PCA Moderator live in the same neighborh

E. Calvin Beisner: Climate and Energy Policy

Knight & Rose Show

January 4, 2026

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose welcome Dr. E. Calvin Beisner to discuss climate and energy policy. They explore Biblical dominion and stewardship, con

Did Jesus Prove He Wasn’t Sinless When He Overturned the Tables?

#STRask

December 29, 2025

Questions about whether Jesus proved he wasn’t sinless when he overturned the tables, whether Jesus’ response to the Pharisees in Mark 3:22–26 was a b

Protestants and Catholics: What’s the Difference? With Chad Van Dixhoorn, Blair Smith, and Mark McDowell

Life and Books and Everything

November 26, 2025

How should Protestants think about the Catholic Mass? About the Eucharist? About the history and development of the papacy? In this panel discussion,

Why Is It Necessary to Believe Jesus Is God?

#STRask

February 19, 2026

Questions about why it’s necessary to believe Jesus is God, whether belief in the Trinity is required for salvation, and why one has to believe in the