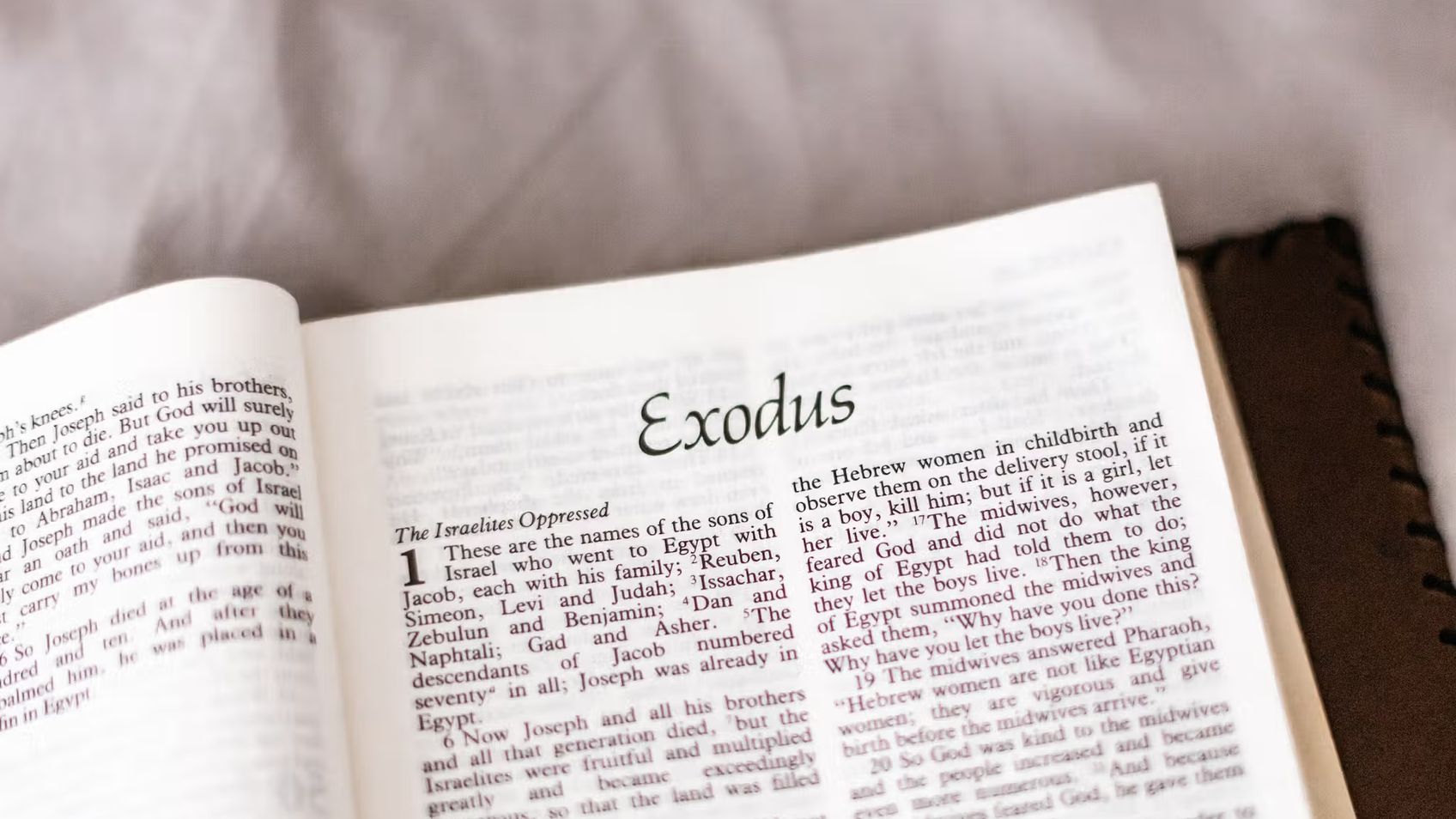

Exodus Introduction to the Law

Exodus — Steve GreggNext in this series

Exodus 20:1 - 20:12 (Commandments 1-4)

Exodus Introduction to the Law

ExodusSteve Gregg

In Steve Gregg's "Exodus Introduction to the Law", the role and significance of the Law of Moses is explored. The Law is viewed positively as embodying moral wisdom directly from God, representing God's unchangeable nature and character. While it includes both moral behavior and worship procedures, the latter only has enduring validity until the coming of Christ. The laws are divided into moral, ceremonial, and civil categories, with civil laws being specific to Israel's political entity and not applicable to Christians today.

More from Exodus

14 of 25

Next in this series

Exodus 20:1 - 20:12 (Commandments 1-4)

Exodus

In Steve Gregg's commentary on Exodus 20:1-12, he highlights the first four commandments as focusing on loving God with all one's heart, soul, mind, a

15 of 25

Exodus 20:13 - 20:17 (Commandments 6-10)

Exodus

In Exodus 20:13-17, the sixth through tenth commandments are outlined. The sixth commandment, "You shall not murder," emphasizes the importance of jus

12 of 25

Exodus 18 - 19

Exodus

The chapters of Exodus 18 and 19 narrate the story of Jethro, Moses' father-in-law, advising him to delegate the responsibility of handling people's d

Series by Steve Gregg

Jude

Steve Gregg provides a comprehensive analysis of the biblical book of Jude, exploring its themes of faith, perseverance, and the use of apocryphal lit

Zephaniah

Experience the prophetic words of Zephaniah, written in 612 B.C., as Steve Gregg vividly brings to life the impending judgement, destruction, and hope

Word of Faith

"Word of Faith" by Steve Gregg is a four-part series that provides a detailed analysis and thought-provoking critique of the Word Faith movement's tea

Church History

Steve Gregg gives a comprehensive overview of church history from the time of the Apostles to the modern day, covering important figures, events, move

Spiritual Warfare

In "Spiritual Warfare," Steve Gregg explores the tactics of the devil, the methods to resist Satan's devices, the concept of demonic possession, and t

The Jewish Roots Movement

"The Jewish Roots Movement" by Steve Gregg is a six-part series that explores Paul's perspective on Torah observance, the distinction between Jewish a

Cultivating Christian Character

Steve Gregg's lecture series focuses on cultivating holiness and Christian character, emphasizing the need to have God's character and to walk in the

Malachi

Steve Gregg's in-depth exploration of the book of Malachi provides insight into why the Israelites were not prospering, discusses God's election, and

How Can I Know That I Am Really Saved?

In this four-part series, Steve Gregg explores the concept of salvation using 1 John as a template and emphasizes the importance of love, faith, godli

Creation and Evolution

In the series "Creation and Evolution" by Steve Gregg, the evidence against the theory of evolution is examined, questioning the scientific foundation

More on OpenTheo

What About Those Who Never Heard the Name of Jesus?

#STRask

December 22, 2025

Questions about what will happen to those who never heard of Jesus or were brought up in a different faith, whether there’s biblical warrant to think

Lora Ries: Border Security and Immigration Policy

Knight & Rose Show

December 7, 2025

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose welcome Lora Ries to discuss border security and immigration policy. They explore Biden's policy changes, like ending R

Sense, Sensibility, and Adam Smith with Jan Van Vliet

Life and Books and Everything

February 16, 2026

This year is a special anniversary for the United States as Americans celebrate 250 years of independence. But 1776 was an important year in more ways

Is It a Sin to Feel Let Down by God?

#STRask

November 6, 2025

Questions about whether it’s a sin to feel let down by God and whether it would be easier to have a personal relationship with a rock than with a God

How Do We Advocate for Christian Policy Without Making the Government Interfere in Every Area of Life?

#STRask

November 20, 2025

Questions about how to advocate for Christian policy without making the government interfere in every area of life, and the differences between the mo

Could the Writers of Scripture Have Been Influenced by Their Fallen Nature?

#STRask

October 23, 2025

Questions about whether or not it’s reasonable to worry that some of our current doctrines were influenced by the fallen nature of the apostles, and h

Kingdom Priorities: Following the Teachings of Jesus

Knight & Rose Show

February 14, 2026

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose discuss Jesus' teachings from the Gospels, emphasizing truth, evidence, self-denial, and forgiveness. They explore pass

Can Two Logical People Come to Conflicting Conclusions Without Committing a Fallacy?

#STRask

January 8, 2026

Questions about whether two logical people can come to conflicting conclusions on a topic without committing a fallacy, how Greg, as a public figure,

Life and Ministry in Charlotte and in the SBC with Clint Pressley

Life and Books and Everything

December 15, 2025

In a rare cultural anomaly that may never be repeated in our lifetimes, the current SBC President and current PCA Moderator live in the same neighborh

The Resurrection Standoff: Licona vs. Ehrman on the Unbelievable Podcast

Risen Jesus

October 22, 2025

This episode is taken from the Unbelievable podcast with Justin Brierly in 2011 when Dr. Bart Ehrman and Dr. Michael Licona address the question: Is t

How Do I Determine Which Topics at Work Are Worth Commenting On?

#STRask

January 5, 2026

Questions about how to determine which topics at work are worth commenting on, and a good way to respond when you’re in a group Bible study and hear e

What Tools of Reasoning Help You Know What’s True, Right, and Good?

#STRask

December 4, 2025

Question about what tools of reasoning help us determine whether something is true or false, right or wrong, good or bad before bringing Scripture int

Conservatism and Religious Freedom with John Wilsey

Life and Books and Everything

October 27, 2025

What is conservatism? And why does it go hand in hand with religious freedom? How should we think about the American experiment of ordered liberty? Ha

How Can We Know Who Is Teaching the Same Gospel Paul Taught?

#STRask

February 16, 2026

Questions about how we can know who is teaching the same gospel Paul taught, and whether or not Jeremiah 1:5 supports the idea that we pre-existed in

Why Does the Bible Teach You How to Be a Proper Slave Owner?

#STRask

November 13, 2025

Question about why it seems like the Bible teaches you how to be a proper slave owner rather than than saying, “Stop it. Give them freedom.”

* It s