Understanding the Prophets (Part 1)

Individual Topics — Steve GreggNext in this series

Understanding the Prophets (Part 2)

Understanding the Prophets (Part 1)

Individual TopicsSteve Gregg

Steve Gregg provides insights into understanding the Old Testament prophets. He emphasizes that prophets are people who speak forth an inspired word from God and deliver it to the people, often in the form of visions, dreams, or hearing God speak to them. The purpose of prophecy was to exhort, edify, and comfort the people of God. Gregg explains how reading the Old Testament prophets alongside the New Testament writers' interpretation can provide a clearer understanding.

More from Individual Topics

97 of 111

Next in this series

Understanding the Prophets (Part 2)

Individual Topics

In this discussion, Steve Gregg explores various interpretations of Old Testament prophecies and the challenges of understanding the prophets. He note

98 of 111

War - A Christian Perspective (Part 1)

Individual Topics

In this discussion on the Christian perspective on war, Steve Gregg acknowledges that not all Christians will agree on the topic, but stresses the imp

95 of 111

True and False Assurance

Individual Topics

In the article "True and False Assurance," Steve Gregg discusses the topic of assurance of salvation. While it is not necessary for individuals to hav

Series by Steve Gregg

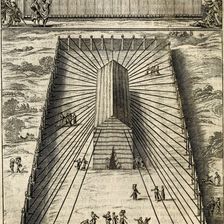

The Tabernacle

"The Tabernacle" is a comprehensive ten-part series that explores the symbolism and significance of the garments worn by priests, the construction and

Psalms

In this 32-part series, Steve Gregg provides an in-depth verse-by-verse analysis of various Psalms, highlighting their themes, historical context, and

Knowing God

Knowing God by Steve Gregg is a 16-part series that delves into the dynamics of relationships with God, exploring the importance of walking with Him,

Ephesians

In this 10-part series, Steve Gregg provides verse by verse teachings and insights through the book of Ephesians, emphasizing themes such as submissio

Sermon on the Mount

Steve Gregg's 14-part series on the Sermon on the Mount deepens the listener's understanding of the Beatitudes and other teachings in Matthew 5-7, emp

Genesis

Steve Gregg provides a detailed analysis of the book of Genesis in this 40-part series, exploring concepts of Christian discipleship, faith, obedience

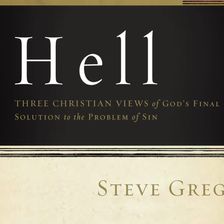

Three Views of Hell

Steve Gregg discusses the three different views held by Christians about Hell: the traditional view, universalism, and annihilationism. He delves into

1 Kings

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the book of 1 Kings, providing insightful commentary on topics such as discernment, building projects, the

3 John

In this series from biblical scholar Steve Gregg, the book of 3 John is examined to illuminate the early developments of church government and leaders

Evangelism

Evangelism by Steve Gregg is a 6-part series that delves into the essence of evangelism and its role in discipleship, exploring the biblical foundatio

More on OpenTheo

Is It Possible There’s a Being That’s Greater Than God?

#STRask

February 5, 2026

Questions about whether it’s possible there’s a being that’s greater than God and that’s outside of God’s comprehension and omniscience, and how to ex

Does Open-Mindedness Require Studying Other Religions Before Becoming a Christian?

#STRask

February 9, 2026

Questions about the claim that if Christians really want to be open-minded, they need to read and study other religions before committing to Christian

An Invitation to the 2026 Coram Deo Pastors Conference

Life and Books and Everything

February 18, 2026

"I love being a pastor, and I love pastors, which is why I hope you will consider joining us at the Coram Deo Pastors Conference in 2026." —Kevin DeYo

The Resurrection Standoff: Licona vs. Ehrman on the Unbelievable Podcast

Risen Jesus

October 22, 2025

This episode is taken from the Unbelievable podcast with Justin Brierly in 2011 when Dr. Bart Ehrman and Dr. Michael Licona address the question: Is t

Can You Recommend Good Books with More In-Depth Information and Ideas?

#STRask

January 22, 2026

Questions about good books on Christian apologetics, philosophy, and theology with more in-depth information and ideas, and resources to help an intel

Life and Ministry in Charlotte and in the SBC with Clint Pressley

Life and Books and Everything

December 15, 2025

In a rare cultural anomaly that may never be repeated in our lifetimes, the current SBC President and current PCA Moderator live in the same neighborh

What Tools of Reasoning Help You Know What’s True, Right, and Good?

#STRask

December 4, 2025

Question about what tools of reasoning help us determine whether something is true or false, right or wrong, good or bad before bringing Scripture int

Did God Create Us So He Wouldn’t Be Alone?

#STRask

November 3, 2025

Questions about whether God created us so he wouldn’t be alone, what he had before us, and a comparison between the Muslim view of God and the Christi

Lora Ries: Border Security and Immigration Policy

Knight & Rose Show

December 7, 2025

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose welcome Lora Ries to discuss border security and immigration policy. They explore Biden's policy changes, like ending R

Protestants and Catholics: What’s the Difference? With Chad Van Dixhoorn, Blair Smith, and Mark McDowell

Life and Books and Everything

November 26, 2025

How should Protestants think about the Catholic Mass? About the Eucharist? About the history and development of the papacy? In this panel discussion,

Does God Really Need a “Pound of Flesh” to Forgive Sins?

#STRask

January 12, 2026

Questions about how to answer the challenge that God doesn’t need a “pound of flesh” to forgive sins but can simply forgive, and whether the claim in

Is 1 Corinthians 12:3 a Black-and-White Tool for Discernment?

#STRask

October 27, 2025

Questions about whether the claim in 1 Corinthians that “no one can say ‘Jesus is Lord’ except in the Holy Spirit” is a black-and-white tool for disce

Shouldn’t I Be Praying for My Soul Rather Than for Material Things?

#STRask

February 2, 2026

Questions about whether we should be praying for our souls rather than for material things, why we need to pray about decisions, whether the devil can

How Do I Determine Which Topics at Work Are Worth Commenting On?

#STRask

January 5, 2026

Questions about how to determine which topics at work are worth commenting on, and a good way to respond when you’re in a group Bible study and hear e

How Do We Advocate for Christian Policy Without Making the Government Interfere in Every Area of Life?

#STRask

November 20, 2025

Questions about how to advocate for Christian policy without making the government interfere in every area of life, and the differences between the mo