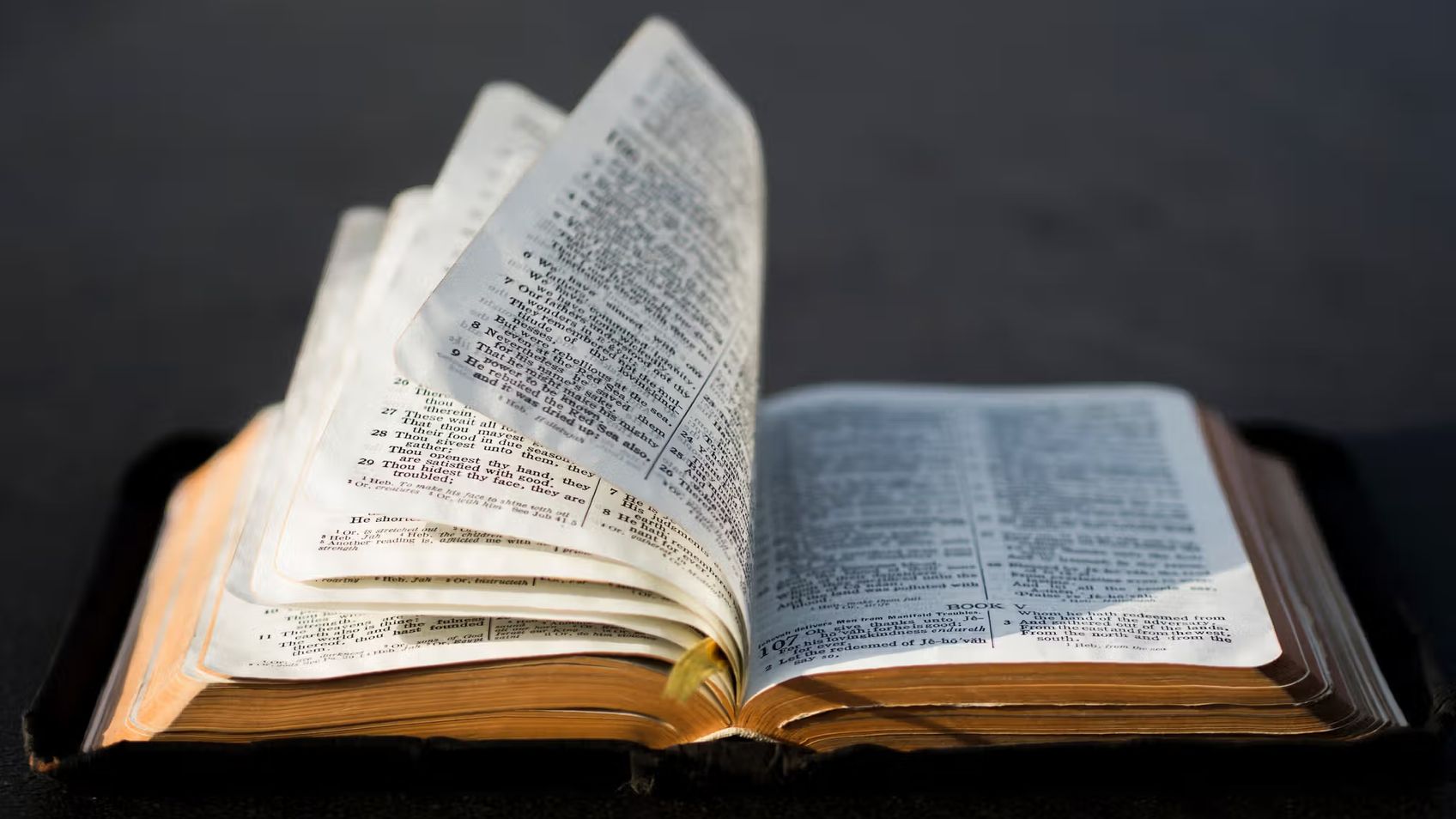

Romans Overview (Part 4)

Bible Book Overviews — Steve GreggNext in this series

1st Corinthians Overview (Part 1)

Romans Overview (Part 4)

Bible Book OverviewsSteve Gregg

In this fourth part of his overview of Romans, Steve Gregg addresses the difficult passage in chapter five regarding the concept of original sin. He discusses the various beliefs held by Christians regarding the impact of Adam's sin on humanity and whether or not babies are born with a sinful nature. Gregg also delves into the topic of the war between the flesh and the spirit, emphasizing the importance of striving to walk in the Spirit in order to fulfill the law of God and overcome sin. Finally, he examines chapters nine through eleven, discussing God's plan of redemption for both Jews and Gentiles and the role of the faithful remnant within Israel.

More from Bible Book Overviews

65 of 80

Next in this series

1st Corinthians Overview (Part 1)

Bible Book Overviews

In this overview of the book of 1 Corinthians, Steve Gregg highlights the various problems encountered by the church of Corinth such as divisions, sex

66 of 80

1st Corinthians Overview (Part 2)

Bible Book Overviews

In this overview of 1 Corinthians, Steve Gregg emphasizes the importance of unity within the church. While there may be differing interpretations of s

63 of 80

Romans Overview (Part 3)

Bible Book Overviews

In this overview of the book of Romans, Steve Gregg highlights the two main sections of the book, namely theological and practical. The first eight ch

Series by Steve Gregg

Joshua

Steve Gregg's 13-part series on the book of Joshua provides insightful analysis and application of key themes including spiritual warfare, obedience t

Exodus

Steve Gregg's "Exodus" is a 25-part teaching series that delves into the book of Exodus verse by verse, covering topics such as the Ten Commandments,

1 Thessalonians

In this three-part series from Steve Gregg, he provides an in-depth analysis of 1 Thessalonians, touching on topics such as sexual purity, eschatology

Leviticus

In this 12-part series, Steve Gregg provides insightful analysis of the book of Leviticus, exploring its various laws and regulations and offering spi

Galatians

In this six-part series, Steve Gregg provides verse-by-verse commentary on the book of Galatians, discussing topics such as true obedience, faith vers

Haggai

In Steve Gregg's engaging exploration of the book of Haggai, he highlights its historical context and key themes often overlooked in this prophetic wo

What Are We to Make of Israel

Steve Gregg explores the intricate implications of certain biblical passages in relation to the future of Israel, highlighting the historical context,

Three Views of Hell

Steve Gregg discusses the three different views held by Christians about Hell: the traditional view, universalism, and annihilationism. He delves into

Gospel of Luke

In this 32-part series, Steve Gregg provides in-depth commentary and historical context on each chapter of the Gospel of Luke, shedding new light on i

Isaiah

A thorough analysis of the book of Isaiah by Steve Gregg, covering various themes like prophecy, eschatology, and the servant songs, providing insight

More on OpenTheo

What Is Wrong with Wokeness? With Neil Shenvi

Life and Books and Everything

January 19, 2026

In this timely interview, Kevin talks to Neil Shenvi about his new book (co-authored with Pat Sawyer), entitled “Post Woke: Asserting a Biblical Visio

How Do We Advocate for Christian Policy Without Making the Government Interfere in Every Area of Life?

#STRask

November 20, 2025

Questions about how to advocate for Christian policy without making the government interfere in every area of life, and the differences between the mo

Is 1 Corinthians 12:3 a Black-and-White Tool for Discernment?

#STRask

October 27, 2025

Questions about whether the claim in 1 Corinthians that “no one can say ‘Jesus is Lord’ except in the Holy Spirit” is a black-and-white tool for disce

An Invitation to the 2026 Coram Deo Pastors Conference

Life and Books and Everything

February 18, 2026

"I love being a pastor, and I love pastors, which is why I hope you will consider joining us at the Coram Deo Pastors Conference in 2026." —Kevin DeYo

Did Jesus Prove He Wasn’t Sinless When He Overturned the Tables?

#STRask

December 29, 2025

Questions about whether Jesus proved he wasn’t sinless when he overturned the tables, whether Jesus’ response to the Pharisees in Mark 3:22–26 was a b

Is It Possible There’s a Being That’s Greater Than God?

#STRask

February 5, 2026

Questions about whether it’s possible there’s a being that’s greater than God and that’s outside of God’s comprehension and omniscience, and how to ex

Why Does the Bible Teach You How to Be a Proper Slave Owner?

#STRask

November 13, 2025

Question about why it seems like the Bible teaches you how to be a proper slave owner rather than than saying, “Stop it. Give them freedom.”

* It s

The Making of the American Mind with Matthew Spalding

Life and Books and Everything

February 2, 2026

The United States is unique in how much attention it pays to its founding, its founders, and its founding documents. Arguably, the most famous and mos

Is Greg Placing His Faith in the Wrong Thing?

#STRask

February 12, 2026

Questions about Greg placing his faith in his personal assessment of which truth claims best match reality rather than in the revelation of God in Jes

How Do You Justify Calling Jesus the Messiah?

#STRask

December 18, 2025

Questions about how one can justify calling Jesus the Messiah when he didn’t fulfill the Hebrew messianic prophecies, and whether the reason for the v

Can Two Logical People Come to Conflicting Conclusions Without Committing a Fallacy?

#STRask

January 8, 2026

Questions about whether two logical people can come to conflicting conclusions on a topic without committing a fallacy, how Greg, as a public figure,

Protestants and Catholics: What’s the Difference? With Chad Van Dixhoorn, Blair Smith, and Mark McDowell

Life and Books and Everything

November 26, 2025

How should Protestants think about the Catholic Mass? About the Eucharist? About the history and development of the papacy? In this panel discussion,

When I Can’t Stop Thinking About Something, Is That God Speaking?

#STRask

December 1, 2025

Questions about whether having a recurring thought is an indication God is speaking to you, what to say to someone who says they sinned because “God t

Does God Really Need a “Pound of Flesh” to Forgive Sins?

#STRask

January 12, 2026

Questions about how to answer the challenge that God doesn’t need a “pound of flesh” to forgive sins but can simply forgive, and whether the claim in

Prove to Me That Jesus Is Not a Created Being

#STRask

January 26, 2026

Questions about why we should think Jesus is not a created being, and what it means to say God became fully human if part of being human means not bei