Challenges to Uncondtional Election (Part 1)

God's Sovereignty and Man's Salvation — Steve GreggNext in this series

Challenges to Unconditional Election (Part 2)

Challenges to Uncondtional Election (Part 1)

God's Sovereignty and Man's SalvationSteve Gregg

In this talk, Steve Gregg addresses the challenges to unconditional election in Calvinism. He argues that the concept of monergism, where God alone does the work, is at odds with the idea of synergism, where man has a role in his own salvation, which was believed by Christians in the first four centuries. Gregg also suggests that while scripture favors unconditional election, it does not say whether it is unconditional or not. He concludes that the focus on unconditional election in Calvinism is limited and that there is no evidence of individual choices leading to heaven or hell.

More from God's Sovereignty and Man's Salvation

8 of 12

Next in this series

Challenges to Unconditional Election (Part 2)

God's Sovereignty and Man's Salvation

Steve Gregg discusses the challenges to the doctrine of unconditional election. He acknowledges that while the Bible states that "No one unless the Fa

9 of 12

Challenges to Limited Atonement

God's Sovereignty and Man's Salvation

In this talk, Steve Gregg challenges the idea of limited atonement, a concept often associated with Calvinism, by emphasizing that Jesus died for all

6 of 12

Challenges to Total Depravity (Part 2)

God's Sovereignty and Man's Salvation

In this segment, Steve Gregg challenges the idea of total depravity from a Calvinistic perspective. He argues that people have the ability to choose g

Series by Steve Gregg

The Jewish Roots Movement

"The Jewish Roots Movement" by Steve Gregg is a six-part series that explores Paul's perspective on Torah observance, the distinction between Jewish a

Toward a Radically Christian Counterculture

Steve Gregg presents a vision for building a distinctive and holy Christian culture that stands in opposition to the values of the surrounding secular

Joshua

Steve Gregg's 13-part series on the book of Joshua provides insightful analysis and application of key themes including spiritual warfare, obedience t

Strategies for Unity

"Strategies for Unity" is a 4-part series discussing the importance of Christian unity, overcoming division, promoting positive relationships, and pri

The Life and Teachings of Christ

This 180-part series by Steve Gregg delves into the life and teachings of Christ, exploring topics such as prayer, humility, resurrection appearances,

Deuteronomy

Steve Gregg provides a comprehensive and insightful commentary on the book of Deuteronomy, discussing the Israelites' relationship with God, the impor

Gospel of Mark

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the Gospel of Mark.

The Narrow Path is the radio and internet ministry of Steve Gregg, a servant Bible tea

Gospel of Matthew

Spanning 72 hours of teaching, Steve Gregg's verse by verse teaching through the Gospel of Matthew provides a thorough examination of Jesus' life and

Leviticus

In this 12-part series, Steve Gregg provides insightful analysis of the book of Leviticus, exploring its various laws and regulations and offering spi

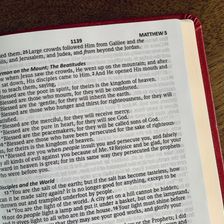

The Beatitudes

Steve Gregg teaches through the Beatitudes in Jesus' Sermon on the Mount.

More on OpenTheo

Can You Recommend Good Books with More In-Depth Information and Ideas?

#STRask

January 22, 2026

Questions about good books on Christian apologetics, philosophy, and theology with more in-depth information and ideas, and resources to help an intel

Could the Writers of Scripture Have Been Influenced by Their Fallen Nature?

#STRask

October 23, 2025

Questions about whether or not it’s reasonable to worry that some of our current doctrines were influenced by the fallen nature of the apostles, and h

Protestants and Catholics: What’s the Difference? With Chad Van Dixhoorn, Blair Smith, and Mark McDowell

Life and Books and Everything

November 26, 2025

How should Protestants think about the Catholic Mass? About the Eucharist? About the history and development of the papacy? In this panel discussion,

Did God Create Us So He Wouldn’t Be Alone?

#STRask

November 3, 2025

Questions about whether God created us so he wouldn’t be alone, what he had before us, and a comparison between the Muslim view of God and the Christi

Kingdom Priorities: Following the Teachings of Jesus

Knight & Rose Show

February 14, 2026

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose discuss Jesus' teachings from the Gospels, emphasizing truth, evidence, self-denial, and forgiveness. They explore pass

Prove to Me That Jesus Is Not a Created Being

#STRask

January 26, 2026

Questions about why we should think Jesus is not a created being, and what it means to say God became fully human if part of being human means not bei

How Do You Justify Calling Jesus the Messiah?

#STRask

December 18, 2025

Questions about how one can justify calling Jesus the Messiah when he didn’t fulfill the Hebrew messianic prophecies, and whether the reason for the v

When I Can’t Stop Thinking About Something, Is That God Speaking?

#STRask

December 1, 2025

Questions about whether having a recurring thought is an indication God is speaking to you, what to say to someone who says they sinned because “God t

The Resurrection Standoff: Licona vs. Ehrman on the Unbelievable Podcast

Risen Jesus

October 22, 2025

This episode is taken from the Unbelievable podcast with Justin Brierly in 2011 when Dr. Bart Ehrman and Dr. Michael Licona address the question: Is t

Is 1 Corinthians 12:3 a Black-and-White Tool for Discernment?

#STRask

October 27, 2025

Questions about whether the claim in 1 Corinthians that “no one can say ‘Jesus is Lord’ except in the Holy Spirit” is a black-and-white tool for disce

Can Two Logical People Come to Conflicting Conclusions Without Committing a Fallacy?

#STRask

January 8, 2026

Questions about whether two logical people can come to conflicting conclusions on a topic without committing a fallacy, how Greg, as a public figure,

Does God Hear the Prayers of Non-Believers?

#STRask

February 26, 2026

Questions about whether or not God hears and answers the prayers of non-believers, and thoughts about a church sign that reads (as if from God), “Just

How Can I Explain Modesty to My Daughter?

#STRask

November 27, 2025

Questions about how to explain modesty to a nine-year-old in a way that won’t cause shame about her body, and when and how to tell a child about a pre

What Tools of Reasoning Help You Know What’s True, Right, and Good?

#STRask

December 4, 2025

Question about what tools of reasoning help us determine whether something is true or false, right or wrong, good or bad before bringing Scripture int

What Do You Think About Churches Advertising on Social Media?

#STRask

January 19, 2026

Questions about whether there’s an issue with churches advertising on social media, whether it’s weird if we pray along with a YouTuber, and whether C