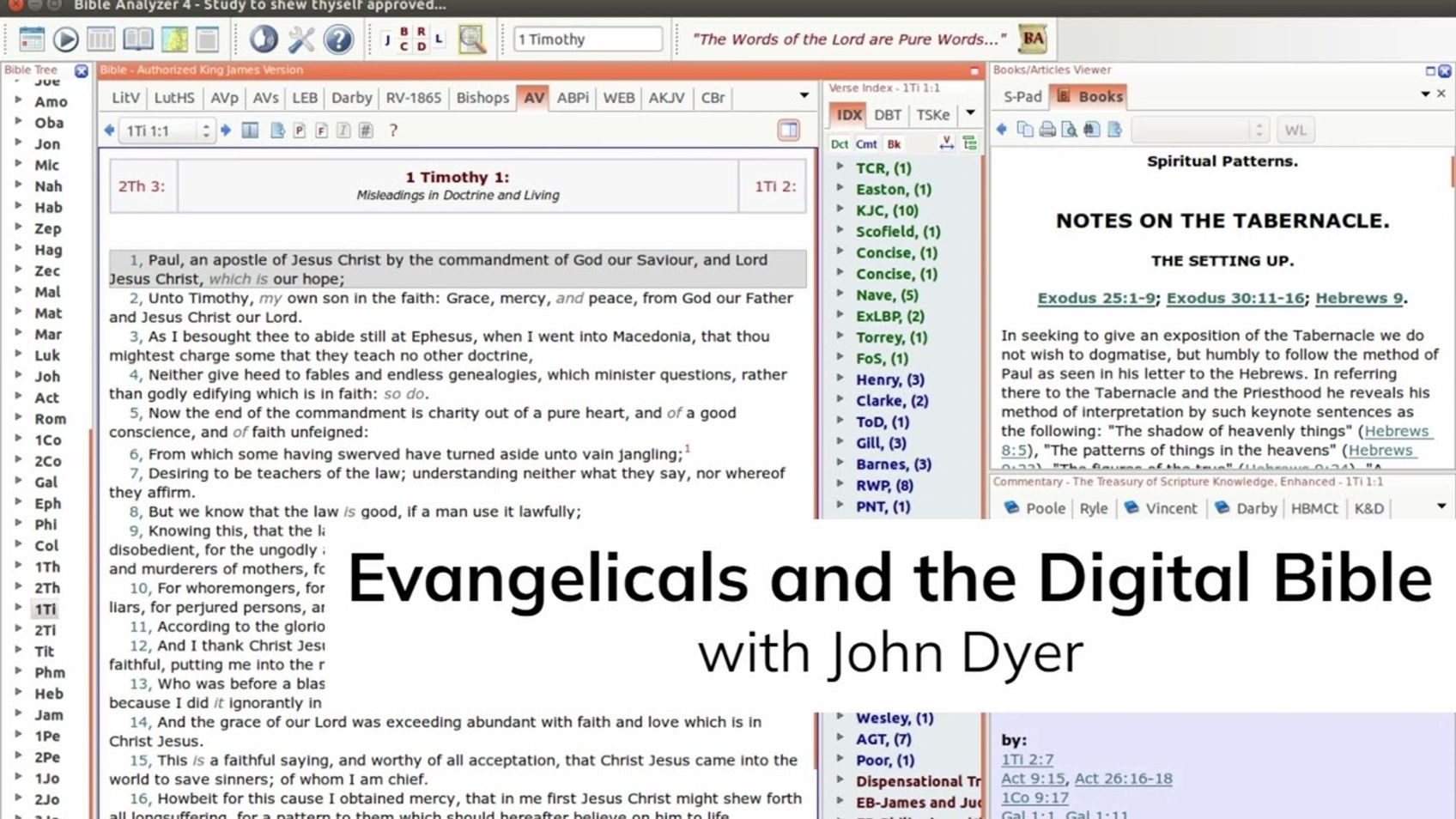

Evangelicals and the Digital Bible (with John Dyer)

John Dyer is the author of the recently published 'People of the Screen: How Evangelicals Created the Digital Bible and How It Shapes Their Reading of Scripture' (https://amzn.to/44Mu1Z3). He joins me to discuss the book and the way that digital Bibles are changing the ways that we engage with Scripture.

I apologize for the low sound quality at points; there were issues with my recording.

If you have enjoyed my videos and podcasts, please tell your friends. If you are interested in supporting my videos and podcasts and my research more generally, please consider supporting my work on Patreon (https://www.patreon.com/zugzwanged), using my PayPal account (https://bit.ly/2RLaUcB), or by buying books for my research on Amazon (https://www.amazon.co.uk/hz/wishlist/ls/36WVSWCK4X33O?ref_=wl_share).

The audio of all of my videos is available on my Soundcloud account: https://soundcloud.com/alastairadversaria. You can also listen to the audio of these episodes on iTunes: https://itunes.apple.com/gb/podcast/alastairs-adversaria/id1416351035?mt=2.

More From Alastair Roberts

More on OpenTheo