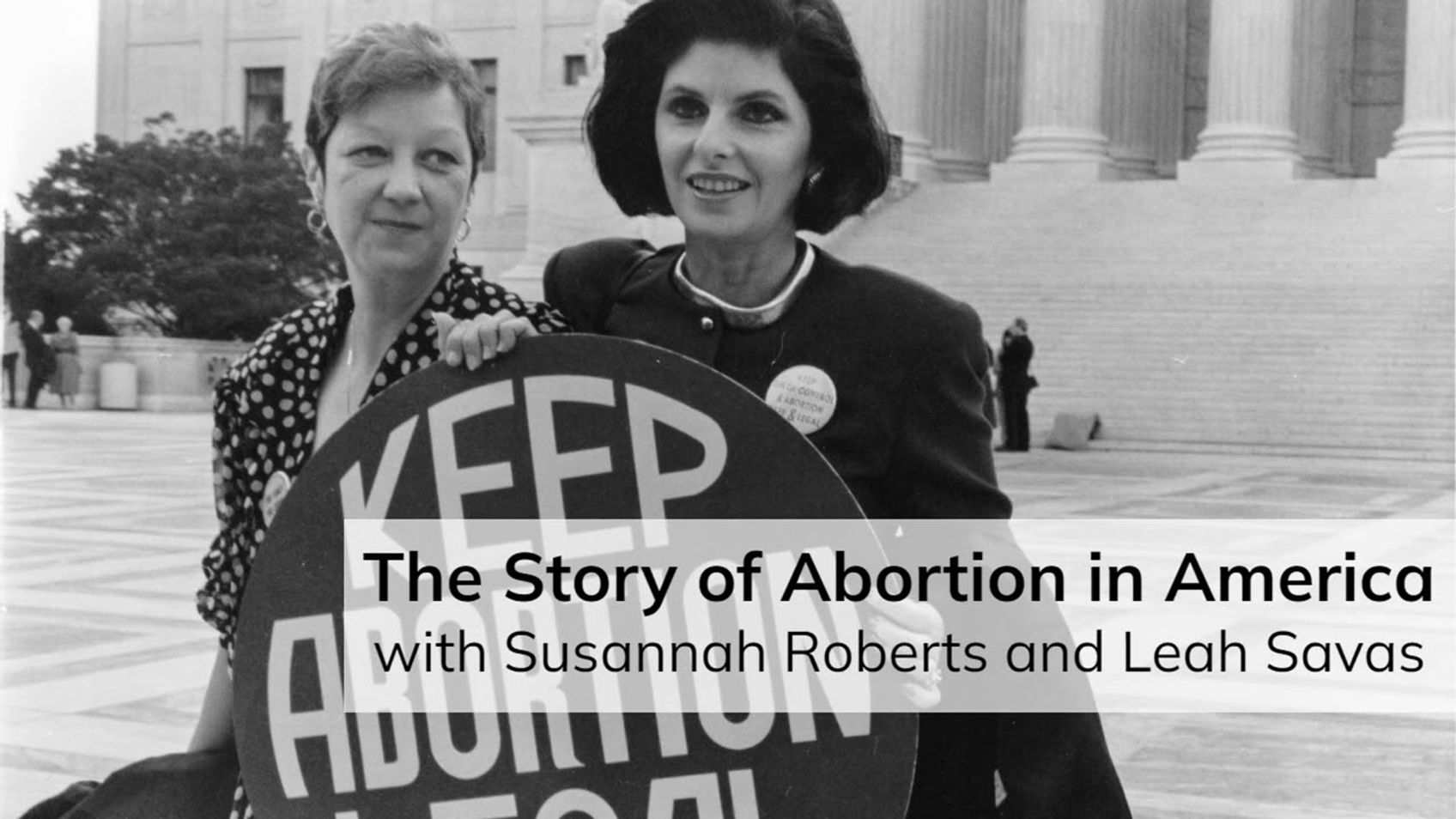

The Story of Abortion in America (with Leah Savas)

Leah Savas, who reports on abortion for WORLD News Group, has written a book with Marvin Olasky, 'The Story of Abortion in America: A Street-Level History, 1652–2022' (https://amzn.to/42PeTtI). She joins me and my wife, Susannah Black Roberts, to discuss the book and the subject of abortion more broadly.

If you have enjoyed my videos and podcasts, please tell your friends. If you are interested in supporting my videos and podcasts and my research more generally, please consider supporting my work on Patreon (https://www.patreon.com/zugzwanged), using my PayPal account (https://bit.ly/2RLaUcB), or by buying books for my research on Amazon (https://www.amazon.co.uk/hz/wishlist/ls/36WVSWCK4X33O?ref_=wl_share).

The audio of all of my videos is available on my Soundcloud account: https://soundcloud.com/alastairadversaria. You can also listen to the audio of these episodes on iTunes: https://itunes.apple.com/gb/podcast/alastairs-adversaria/id1416351035?mt=2.

More From Alastair Roberts

More on OpenTheo