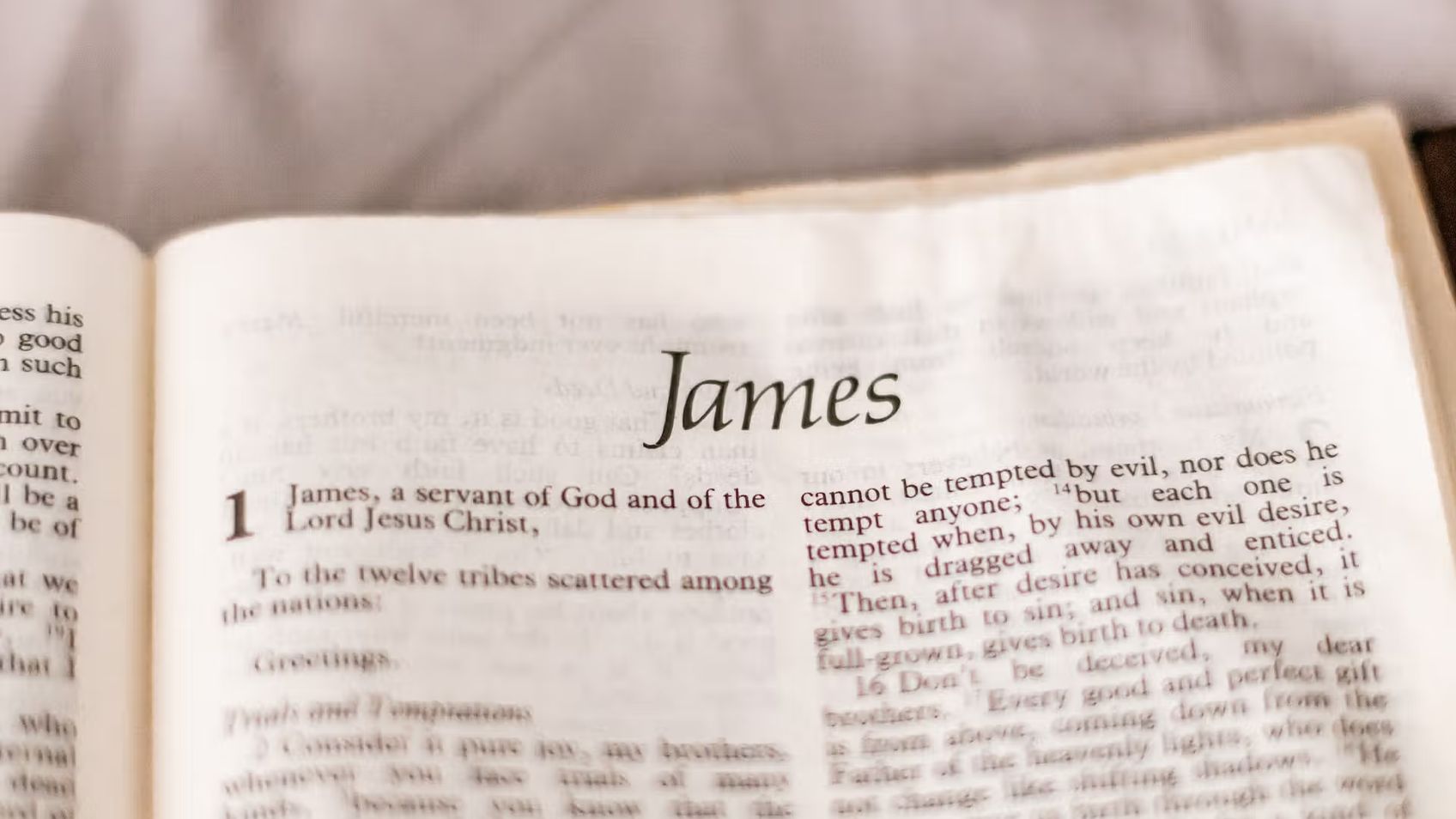

James 3:13 - 4:4

JamesSteve Gregg

James 3:13 - 4:4 is a passage warning against the damaging effects of speech, specifically addressing teachers and their power to do harm. True wisdom involves understanding the importance of using our words for good, rather than for envy or self-seeking. The passage also touches on the issue of war, urging Christians to value peace and leave vengeance in the hands of God.

More from James

5 of 5

Next in this series

James 4:5 - 5:20

James

James warns against the dangers of loving the world and pursuing worldly objectives, as it is a form of spiritual adultery. He advises Christians to r

3 of 5

James 2:8 - 3:12

James

James 2:8-3:12 is a call to reject favoritism and show mercy to others as a reflection of one's own receiving of mercy from God. The passage emphasize

Series by Steve Gregg

Hebrews

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the book of Hebrews, focusing on themes, warnings, the new covenant, judgment, faith, Jesus' authority, and

Psalms

In this 32-part series, Steve Gregg provides an in-depth verse-by-verse analysis of various Psalms, highlighting their themes, historical context, and

1 Corinthians

Steve Gregg provides a verse-by-verse exposition of 1 Corinthians, delving into themes such as love, spiritual gifts, holiness, and discipline within

Ezra

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the book of Ezra, providing historical context, insights, and commentary on the challenges faced by the Jew

Judges

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the Book of Judges in this 16-part series, exploring its historical and cultural context and highlighting t

Church History

Steve Gregg gives a comprehensive overview of church history from the time of the Apostles to the modern day, covering important figures, events, move

Philemon

Steve Gregg teaches a verse-by-verse study of the book of Philemon, examining the historical context and themes, and drawing insights from Paul's pray

Making Sense Out Of Suffering

In "Making Sense Out Of Suffering," Steve Gregg delves into the philosophical question of why a good sovereign God allows suffering in the world.

Toward a Radically Christian Counterculture

Steve Gregg presents a vision for building a distinctive and holy Christian culture that stands in opposition to the values of the surrounding secular

Deuteronomy

Steve Gregg provides a comprehensive and insightful commentary on the book of Deuteronomy, discussing the Israelites' relationship with God, the impor

More on OpenTheo

Why Should We Pray If God Already Knows What’s Going to Happen?

#STRask

January 29, 2026

Questions about why we should pray if God already knows what’s going to happen, how the effectiveness of prayer is measured, and whether or not things

E. Calvin Beisner: Climate and Energy Policy

Knight & Rose Show

January 4, 2026

Wintery Knight and Desert Rose welcome Dr. E. Calvin Beisner to discuss climate and energy policy. They explore Biblical dominion and stewardship, con

Are Demon Possessions and Exorcisms in the New Testament Literal?

#STRask

December 11, 2025

Questions about whether references to demon possessions and exorcisms in the New Testament are literal, how to talk to young children about ghosts, an

Is It a Sin to Feel Let Down by God?

#STRask

November 6, 2025

Questions about whether it’s a sin to feel let down by God and whether it would be easier to have a personal relationship with a rock than with a God

Why Do We Say Someone Was Saved on a Particular Date If It Was Part of an Eternal Plan?

#STRask

November 24, 2025

Questions about why we say someone was saved on a particular date if it was part of an eternal plan, the Roman Catholic view of the gospel vs. the Bib

Sense, Sensibility, and Adam Smith with Jan Van Vliet

Life and Books and Everything

February 16, 2026

This year is a special anniversary for the United States as Americans celebrate 250 years of independence. But 1776 was an important year in more ways

An Invitation to the 2026 Coram Deo Pastors Conference

Life and Books and Everything

February 18, 2026

"I love being a pastor, and I love pastors, which is why I hope you will consider joining us at the Coram Deo Pastors Conference in 2026." —Kevin DeYo

Can You Provide Verifiable, Non-Religious Evidence That a Supernatural Jesus Existed?

#STRask

November 10, 2025

Question about providing verifiable, non-religious evidence that a supernatural Jesus existed.

* I am an atheist and militantly anti-god-belief. Ho

Is Greg Placing His Faith in the Wrong Thing?

#STRask

February 12, 2026

Questions about Greg placing his faith in his personal assessment of which truth claims best match reality rather than in the revelation of God in Jes

How Do You Justify Calling Jesus the Messiah?

#STRask

December 18, 2025

Questions about how one can justify calling Jesus the Messiah when he didn’t fulfill the Hebrew messianic prophecies, and whether the reason for the v

Why Is It Necessary to Believe Jesus Is God?

#STRask

February 19, 2026

Questions about why it’s necessary to believe Jesus is God, whether belief in the Trinity is required for salvation, and why one has to believe in the

Christmas Cranks and Christmas Blessings with Justin Taylor and Collin Hansen

Life and Books and Everything

December 17, 2025

If you are looking for a podcast where three friends talk about whatever they want to talk about and ramble on about sports, books, and grievances, th

How Do We Advocate for Christian Policy Without Making the Government Interfere in Every Area of Life?

#STRask

November 20, 2025

Questions about how to advocate for Christian policy without making the government interfere in every area of life, and the differences between the mo

Keri Ingraham: School Choice and Education Reform

Knight & Rose Show

January 24, 2026

Wintery Knight and guest host Bonnie welcome Dr. Keri Ingraham to discuss school choice and education reform. They discuss the public school monopoly'

What Are Some Good Ways to Start a Conversation About God with Family Members?

#STRask

October 30, 2025

Questions about how to start a conversation about God with non-Christian family members, how to keep from becoming emotional when discussing faith iss