Romans Intro (Part 2)

RomansSteve Gregg

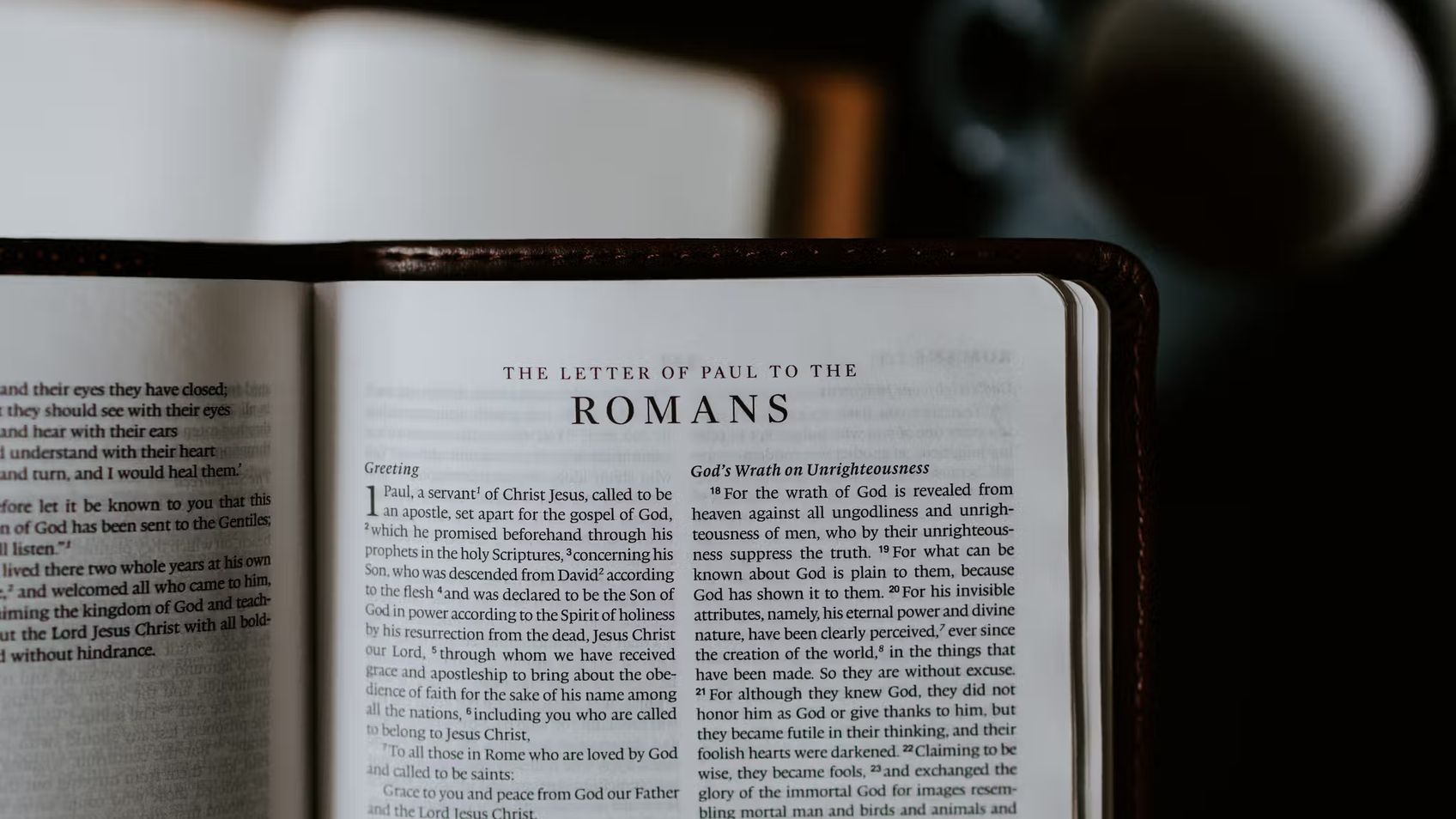

This text provides an overview of the book of Romans, which was written to the church in Rome by Paul around 55-57 BC. Paul uses a variety of metaphors, such as marriage, family, and employment, to illustrate the themes of righteousness and the fulfillment of God's covenant with his people. The book emphasizes that salvation cannot be earned, but is a free gift of God's grace. Through his death and resurrection, believers are now in a covenant relationship with Christ, and bear fruit through him, not through legalistic obedience.

More from Romans

3 of 29

Next in this series

Romans Intro (Part 3)

Romans

An outline of the book of Romans is necessary for grasping its message, as it covers various themes and shifts directions frequently. The traditional

4 of 29

Romans 1 (Part 1)

Romans

The first half of Romans 1 according to Paul's letter emphasizes that the gospel message was not new, but rather a fulfilled promise from the Old Test

1 of 29

Romans Intro (Part 1)

Romans

In this discussion, the insights offered by Paul in the book of Romans are acknowledged as valuable and worthy of close examination. Written in an imp

Series by Steve Gregg

Psalms

In this 32-part series, Steve Gregg provides an in-depth verse-by-verse analysis of various Psalms, highlighting their themes, historical context, and

Genuinely Following Jesus

Steve Gregg's lecture series on discipleship emphasizes the importance of following Jesus and becoming more like Him in character and values. He highl

2 Peter

This series features Steve Gregg teaching verse by verse through the book of 2 Peter, exploring topics such as false prophets, the importance of godli

Evangelism

Evangelism by Steve Gregg is a 6-part series that delves into the essence of evangelism and its role in discipleship, exploring the biblical foundatio

The Beatitudes

Steve Gregg teaches through the Beatitudes in Jesus' Sermon on the Mount.

Colossians

In this 8-part series from Steve Gregg, listeners are taken on an insightful journey through the book of Colossians, exploring themes of transformatio

2 Corinthians

This series by Steve Gregg is a verse-by-verse study through 2 Corinthians, covering various themes such as new creation, justification, comfort durin

How Can I Know That I Am Really Saved?

In this four-part series, Steve Gregg explores the concept of salvation using 1 John as a template and emphasizes the importance of love, faith, godli

Original Sin & Depravity

In this two-part series by Steve Gregg, he explores the theological concepts of Original Sin and Human Depravity, delving into different perspectives

Message For The Young

In this 6-part series, Steve Gregg emphasizes the importance of pursuing godliness and avoiding sinful behavior as a Christian, encouraging listeners

More on OpenTheo

An Invitation to the 2026 Coram Deo Pastors Conference

Life and Books and Everything

February 18, 2026

"I love being a pastor, and I love pastors, which is why I hope you will consider joining us at the Coram Deo Pastors Conference in 2026." —Kevin DeYo

Why Should We Pray If God Already Knows What’s Going to Happen?

#STRask

January 29, 2026

Questions about why we should pray if God already knows what’s going to happen, how the effectiveness of prayer is measured, and whether or not things

Conservatism and Religious Freedom with John Wilsey

Life and Books and Everything

October 27, 2025

What is conservatism? And why does it go hand in hand with religious freedom? How should we think about the American experiment of ordered liberty? Ha

The Making of the American Mind with Matthew Spalding

Life and Books and Everything

February 2, 2026

The United States is unique in how much attention it pays to its founding, its founders, and its founding documents. Arguably, the most famous and mos

Life and Ministry in Charlotte and in the SBC with Clint Pressley

Life and Books and Everything

December 15, 2025

In a rare cultural anomaly that may never be repeated in our lifetimes, the current SBC President and current PCA Moderator live in the same neighborh

Does God Hear the Prayers of Non-Believers?

#STRask

February 26, 2026

Questions about whether or not God hears and answers the prayers of non-believers, and thoughts about a church sign that reads (as if from God), “Just

Can You Provide Verifiable, Non-Religious Evidence That a Supernatural Jesus Existed?

#STRask

November 10, 2025

Question about providing verifiable, non-religious evidence that a supernatural Jesus existed.

* I am an atheist and militantly anti-god-belief. Ho

Prove to Me That Jesus Is Not a Created Being

#STRask

January 26, 2026

Questions about why we should think Jesus is not a created being, and what it means to say God became fully human if part of being human means not bei

Shouldn’t I Be Praying for My Soul Rather Than for Material Things?

#STRask

February 2, 2026

Questions about whether we should be praying for our souls rather than for material things, why we need to pray about decisions, whether the devil can

The Heidelberg Catechism with R. Scott Clark

Life and Books and Everything

November 3, 2025

You may not think you need 1,000 pages on the Heidelberg Catechism, but you do! R. Scott Clark, professor at Westminster Seminary California, has writ

Did Jesus Prove He Wasn’t Sinless When He Overturned the Tables?

#STRask

December 29, 2025

Questions about whether Jesus proved he wasn’t sinless when he overturned the tables, whether Jesus’ response to the Pharisees in Mark 3:22–26 was a b

Is Greg Placing His Faith in the Wrong Thing?

#STRask

February 12, 2026

Questions about Greg placing his faith in his personal assessment of which truth claims best match reality rather than in the revelation of God in Jes

Keri Ingraham: School Choice and Education Reform

Knight & Rose Show

January 24, 2026

Wintery Knight and guest host Bonnie welcome Dr. Keri Ingraham to discuss school choice and education reform. They discuss the public school monopoly'

Sense, Sensibility, and Adam Smith with Jan Van Vliet

Life and Books and Everything

February 16, 2026

This year is a special anniversary for the United States as Americans celebrate 250 years of independence. But 1776 was an important year in more ways

Why Are So Many Christians Condemning LGB People Just Because of How They Love?

#STRask

January 15, 2026

Questions about Christians condemning LGB people just because of how they love, how God can expect someone to be celibate when others are free to marr