Romans Intro (Part 3)

RomansSteve Gregg

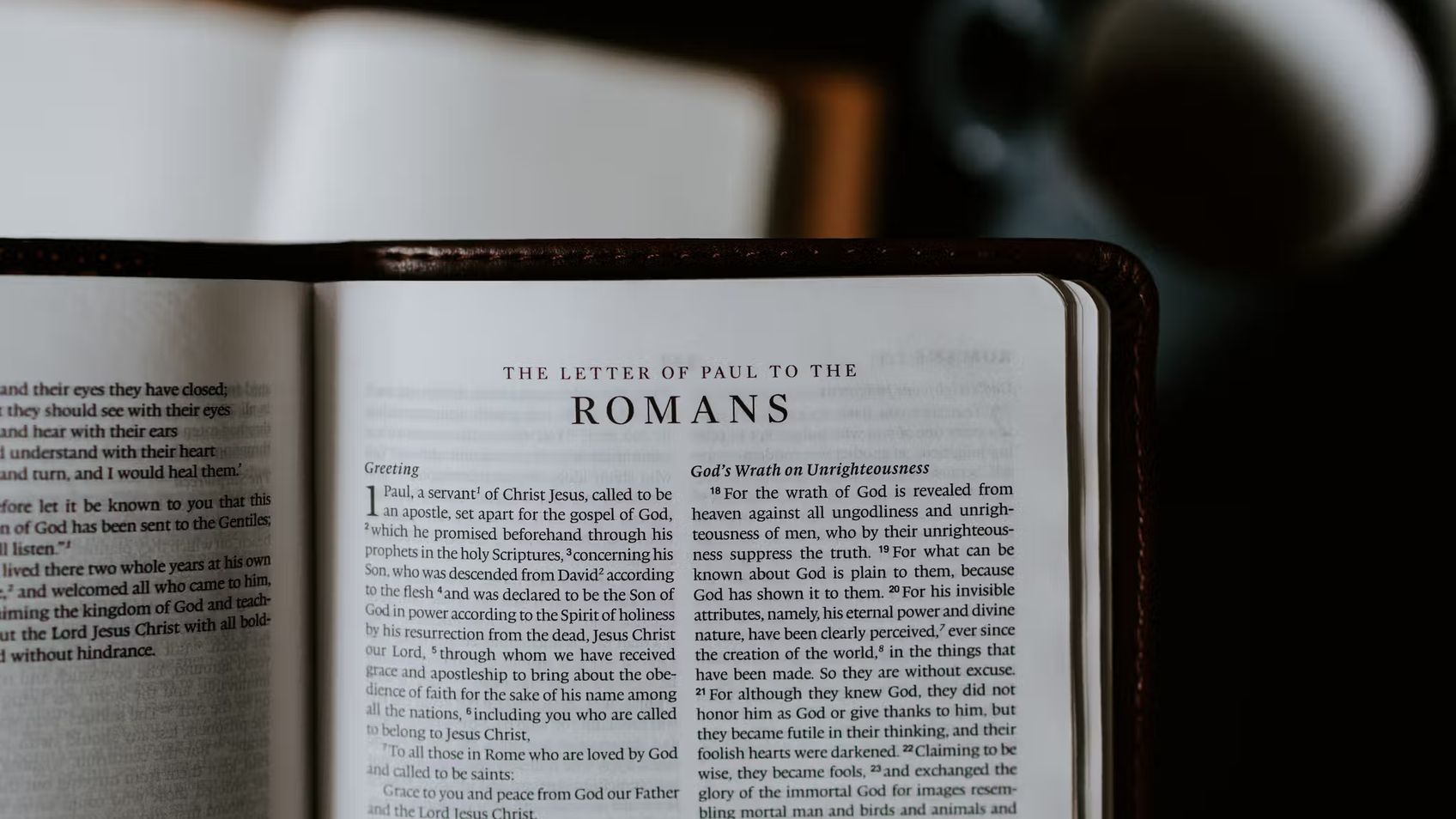

An outline of the book of Romans is necessary for grasping its message, as it covers various themes and shifts directions frequently. The traditional outline of the book centers on the theological treatise of the initial eleven chapters, followed by practical subjects in the latter part. Chapters one through eight of Romans detail the Gospel of salvation, with Paul making a progression of arguments for its positions, starting with the concept of universal sinfulness. Meanwhile, Chapters nine through eleven address a different subject, Israel, and God's guarantees to them.

More from Romans

4 of 29

Next in this series

Romans 1 (Part 1)

Romans

The first half of Romans 1 according to Paul's letter emphasizes that the gospel message was not new, but rather a fulfilled promise from the Old Test

5 of 29

Romans 1 (Part 2)

Romans

In this discussion, Steve Gregg offers insights into the second part of Romans 1, exploring the meaning of phrases and words in their historical and b

2 of 29

Romans Intro (Part 2)

Romans

This text provides an overview of the book of Romans, which was written to the church in Rome by Paul around 55-57 BC. Paul uses a variety of metaphor

Series by Steve Gregg

Genuinely Following Jesus

Steve Gregg's lecture series on discipleship emphasizes the importance of following Jesus and becoming more like Him in character and values. He highl

Obadiah

Steve Gregg provides a thorough examination of the book of Obadiah, exploring the conflict between Israel and Edom and how it relates to divine judgem

Charisma and Character

In this 16-part series, Steve Gregg discusses various gifts of the Spirit, including prophecy, joy, peace, and humility, and emphasizes the importance

Ezra

Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the book of Ezra, providing historical context, insights, and commentary on the challenges faced by the Jew

The Jewish Roots Movement

"The Jewish Roots Movement" by Steve Gregg is a six-part series that explores Paul's perspective on Torah observance, the distinction between Jewish a

3 John

In this series from biblical scholar Steve Gregg, the book of 3 John is examined to illuminate the early developments of church government and leaders

1 Corinthians

Steve Gregg provides a verse-by-verse exposition of 1 Corinthians, delving into themes such as love, spiritual gifts, holiness, and discipline within

Malachi

Steve Gregg's in-depth exploration of the book of Malachi provides insight into why the Israelites were not prospering, discusses God's election, and

Proverbs

In this 34-part series, Steve Gregg offers in-depth analysis and insightful discussion of biblical book Proverbs, covering topics such as wisdom, spee

2 Peter

This series features Steve Gregg teaching verse by verse through the book of 2 Peter, exploring topics such as false prophets, the importance of godli

More on OpenTheo

What Is Wrong with Wokeness? With Neil Shenvi

Life and Books and Everything

January 19, 2026

In this timely interview, Kevin talks to Neil Shenvi about his new book (co-authored with Pat Sawyer), entitled “Post Woke: Asserting a Biblical Visio

Does God Hear the Prayers of Non-Believers?

#STRask

February 26, 2026

Questions about whether or not God hears and answers the prayers of non-believers, and thoughts about a church sign that reads (as if from God), “Just

Can Two Logical People Come to Conflicting Conclusions Without Committing a Fallacy?

#STRask

January 8, 2026

Questions about whether two logical people can come to conflicting conclusions on a topic without committing a fallacy, how Greg, as a public figure,

Prove to Me That Jesus Is Not a Created Being

#STRask

January 26, 2026

Questions about why we should think Jesus is not a created being, and what it means to say God became fully human if part of being human means not bei

The Man on the Middle Cross with Alistair Begg

Life and Books and Everything

November 10, 2025

If you haven’t seen the viral clip, go see it right now. In this episode, Kevin talks to Alistair about the preaching clip he didn’t intend to give, h

Does God Really Need a “Pound of Flesh” to Forgive Sins?

#STRask

January 12, 2026

Questions about how to answer the challenge that God doesn’t need a “pound of flesh” to forgive sins but can simply forgive, and whether the claim in

Shouldn’t I Be Praying for My Soul Rather Than for Material Things?

#STRask

February 2, 2026

Questions about whether we should be praying for our souls rather than for material things, why we need to pray about decisions, whether the devil can

Why Is It Necessary to Believe Jesus Is God?

#STRask

February 19, 2026

Questions about why it’s necessary to believe Jesus is God, whether belief in the Trinity is required for salvation, and why one has to believe in the

Conservatism and Religious Freedom with John Wilsey

Life and Books and Everything

October 27, 2025

What is conservatism? And why does it go hand in hand with religious freedom? How should we think about the American experiment of ordered liberty? Ha

How Do We Advocate for Christian Policy Without Making the Government Interfere in Every Area of Life?

#STRask

November 20, 2025

Questions about how to advocate for Christian policy without making the government interfere in every area of life, and the differences between the mo

What Is the Role of the Holy Spirit in Our Lives if He Doesn’t Give Us Instructions?

#STRask

February 23, 2026

Questions about the role of the Holy Spirit in our lives, advice for someone who believes in God intellectually but struggles to understand how to hav

Why Are So Many Christians Condemning LGB People Just Because of How They Love?

#STRask

January 15, 2026

Questions about Christians condemning LGB people just because of how they love, how God can expect someone to be celibate when others are free to marr

What Do You Think About Churches Advertising on Social Media?

#STRask

January 19, 2026

Questions about whether there’s an issue with churches advertising on social media, whether it’s weird if we pray along with a YouTuber, and whether C

What Tools of Reasoning Help You Know What’s True, Right, and Good?

#STRask

December 4, 2025

Question about what tools of reasoning help us determine whether something is true or false, right or wrong, good or bad before bringing Scripture int

What About Those Who Never Heard the Name of Jesus?

#STRask

December 22, 2025

Questions about what will happen to those who never heard of Jesus or were brought up in a different faith, whether there’s biblical warrant to think