Romans Intro (Part 1)

RomansSteve Gregg

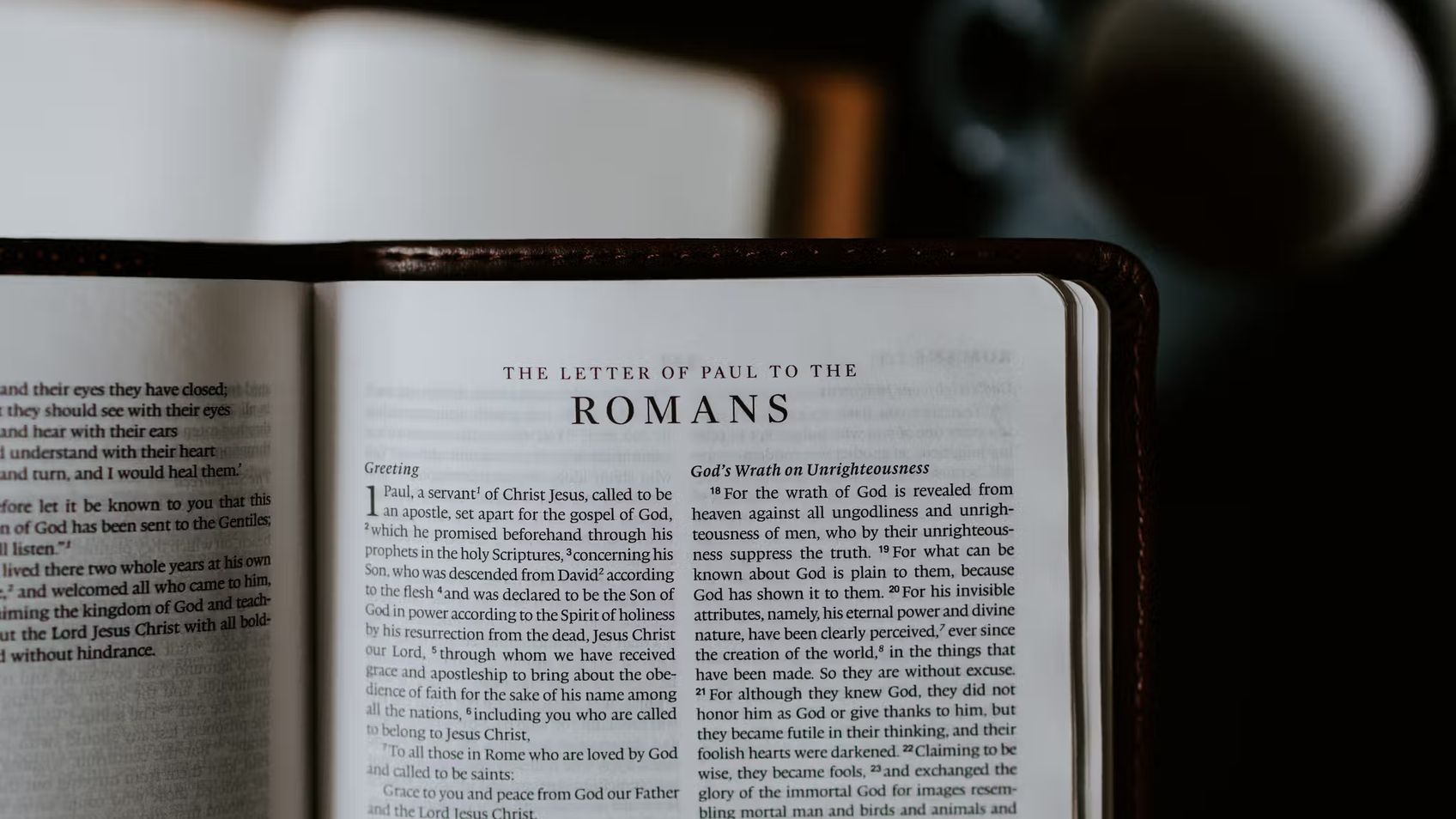

In this discussion, the insights offered by Paul in the book of Romans are acknowledged as valuable and worthy of close examination. Written in an impersonal, didactic style, Romans became Paul's greatest work and has had a profound impact on the Christian faith. Paul addresses the issue of division within the church, emphasizing the need for unity and mutual respect - including the tolerance of differing cultural practices, without judgment or condemnation.

More from Romans

2 of 29

Next in this series

Romans Intro (Part 2)

Romans

This text provides an overview of the book of Romans, which was written to the church in Rome by Paul around 55-57 BC. Paul uses a variety of metaphor

3 of 29

Romans Intro (Part 3)

Romans

An outline of the book of Romans is necessary for grasping its message, as it covers various themes and shifts directions frequently. The traditional

Series by Steve Gregg

Malachi

Steve Gregg's in-depth exploration of the book of Malachi provides insight into why the Israelites were not prospering, discusses God's election, and

What You Absolutely Need To Know Before You Get Married

Steve Gregg's lecture series on marriage emphasizes the gravity of the covenant between two individuals and the importance of understanding God's defi

Joshua

Steve Gregg's 13-part series on the book of Joshua provides insightful analysis and application of key themes including spiritual warfare, obedience t

Leviticus

In this 12-part series, Steve Gregg provides insightful analysis of the book of Leviticus, exploring its various laws and regulations and offering spi

Deuteronomy

Steve Gregg provides a comprehensive and insightful commentary on the book of Deuteronomy, discussing the Israelites' relationship with God, the impor

Gospel of Matthew

Spanning 72 hours of teaching, Steve Gregg's verse by verse teaching through the Gospel of Matthew provides a thorough examination of Jesus' life and

Exodus

Steve Gregg's "Exodus" is a 25-part teaching series that delves into the book of Exodus verse by verse, covering topics such as the Ten Commandments,

God's Sovereignty and Man's Salvation

Steve Gregg explores the theological concepts of God's sovereignty and man's salvation, discussing topics such as unconditional election, limited aton

Zechariah

Steve Gregg provides a comprehensive guide to the book of Zechariah, exploring its historical context, prophecies, and symbolism through ten lectures.

Colossians

In this 8-part series from Steve Gregg, listeners are taken on an insightful journey through the book of Colossians, exploring themes of transformatio

More on OpenTheo

Does Open-Mindedness Require Studying Other Religions Before Becoming a Christian?

#STRask

February 9, 2026

Questions about the claim that if Christians really want to be open-minded, they need to read and study other religions before committing to Christian

Did God Create Us So He Wouldn’t Be Alone?

#STRask

November 3, 2025

Questions about whether God created us so he wouldn’t be alone, what he had before us, and a comparison between the Muslim view of God and the Christi

Is Greg Placing His Faith in the Wrong Thing?

#STRask

February 12, 2026

Questions about Greg placing his faith in his personal assessment of which truth claims best match reality rather than in the revelation of God in Jes

Did Jesus Prove He Wasn’t Sinless When He Overturned the Tables?

#STRask

December 29, 2025

Questions about whether Jesus proved he wasn’t sinless when he overturned the tables, whether Jesus’ response to the Pharisees in Mark 3:22–26 was a b

Can You Recommend Good Books with More In-Depth Information and Ideas?

#STRask

January 22, 2026

Questions about good books on Christian apologetics, philosophy, and theology with more in-depth information and ideas, and resources to help an intel

Christmas Cranks and Christmas Blessings with Justin Taylor and Collin Hansen

Life and Books and Everything

December 17, 2025

If you are looking for a podcast where three friends talk about whatever they want to talk about and ramble on about sports, books, and grievances, th

Why Would Any Rational Person Have to Use Any Religious Book?

#STRask

December 8, 2025

Questions about why any rational person would have to use any religious book, whether apologetics would be redundant if there were actually a good, un

Could the Writers of Scripture Have Been Influenced by Their Fallen Nature?

#STRask

October 23, 2025

Questions about whether or not it’s reasonable to worry that some of our current doctrines were influenced by the fallen nature of the apostles, and h

What Is Wrong with Wokeness? With Neil Shenvi

Life and Books and Everything

January 19, 2026

In this timely interview, Kevin talks to Neil Shenvi about his new book (co-authored with Pat Sawyer), entitled “Post Woke: Asserting a Biblical Visio

Can You Provide Verifiable, Non-Religious Evidence That a Supernatural Jesus Existed?

#STRask

November 10, 2025

Question about providing verifiable, non-religious evidence that a supernatural Jesus existed.

* I am an atheist and militantly anti-god-belief. Ho

Why Does the Bible Teach You How to Be a Proper Slave Owner?

#STRask

November 13, 2025

Question about why it seems like the Bible teaches you how to be a proper slave owner rather than than saying, “Stop it. Give them freedom.”

* It s

How Do We Advocate for Christian Policy Without Making the Government Interfere in Every Area of Life?

#STRask

November 20, 2025

Questions about how to advocate for Christian policy without making the government interfere in every area of life, and the differences between the mo

How Can I Explain Modesty to My Daughter?

#STRask

November 27, 2025

Questions about how to explain modesty to a nine-year-old in a way that won’t cause shame about her body, and when and how to tell a child about a pre

Prove to Me That Jesus Is Not a Created Being

#STRask

January 26, 2026

Questions about why we should think Jesus is not a created being, and what it means to say God became fully human if part of being human means not bei

Keri Ingraham: School Choice and Education Reform

Knight & Rose Show

January 24, 2026

Wintery Knight and guest host Bonnie welcome Dr. Keri Ingraham to discuss school choice and education reform. They discuss the public school monopoly'