Isaiah Overview (Part 1)

Bible Book Overviews — Steve GreggNext in this series

Isaiah Overview (Part 2)

Isaiah Overview (Part 1)

Bible Book OverviewsSteve Gregg

In this overview of Isaiah by Steve Gregg, we learn that Isaiah was a prophet, poet, historian, and statesman who had significant political influence across various kings in his time. His book is divided into two sections, the first dealing with the threat from Assyria, and the second with the threat from Babylon. There is controversy among scholars about whether Isaiah wrote the entire book or if it was written by multiple authors. However, Isaiah's book contains both poetry and historical narratives, with chapters 36-39 being almost identical to the historical accounts in 2 Kings.

More from Bible Book Overviews

30 of 80

Next in this series

Isaiah Overview (Part 2)

Bible Book Overviews

In this overview, Steve Gregg discusses the authorship and themes of the Book of Isaiah, as well as some controversies surrounding it. While some scho

31 of 80

Jeremiah Overview

Bible Book Overviews

In this overview, Steve Gregg delves into the historical context and major themes of the book of Jeremiah in the Bible. Jeremiah, a true prophet who c

28 of 80

Song of Solomon (Overview)

Bible Book Overviews

In this overview, Steve Gregg delves into the Song of Solomon, a short but passionate love story between a man and woman in the Bible. The book uses s

Series by Steve Gregg

Authority of Scriptures

Steve Gregg teaches on the authority of the Scriptures.

The Narrow Path is the radio and internet ministry of Steve Gregg, a servant Bible teacher to

The Jewish Roots Movement

"The Jewish Roots Movement" by Steve Gregg is a six-part series that explores Paul's perspective on Torah observance, the distinction between Jewish a

Wisdom Literature

In this four-part series, Steve Gregg explores the wisdom literature of the Bible, emphasizing the importance of godly behavior and understanding the

Gospel of John

In this 38-part series, Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the Gospel of John, providing insightful analysis and exploring important themes su

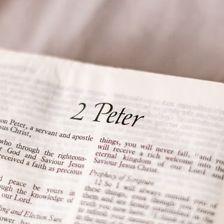

2 Peter

This series features Steve Gregg teaching verse by verse through the book of 2 Peter, exploring topics such as false prophets, the importance of godli

Jude

Steve Gregg provides a comprehensive analysis of the biblical book of Jude, exploring its themes of faith, perseverance, and the use of apocryphal lit

Cultivating Christian Character

Steve Gregg's lecture series focuses on cultivating holiness and Christian character, emphasizing the need to have God's character and to walk in the

Gospel of Matthew

Spanning 72 hours of teaching, Steve Gregg's verse by verse teaching through the Gospel of Matthew provides a thorough examination of Jesus' life and

Job

In this 11-part series, Steve Gregg teaches verse by verse through the book of Job, discussing topics such as suffering, wisdom, and God's role in hum

Titus

In this four-part series from Steve Gregg, listeners are taken on an insightful journey through the book of Titus, exploring issues such as good works

More on OpenTheo

Are Demon Possessions and Exorcisms in the New Testament Literal?

#STRask

December 11, 2025

Questions about whether references to demon possessions and exorcisms in the New Testament are literal, how to talk to young children about ghosts, an

Does God Hear the Prayers of Non-Believers?

#STRask

February 26, 2026

Questions about whether or not God hears and answers the prayers of non-believers, and thoughts about a church sign that reads (as if from God), “Just

How Can We Know Who Is Teaching the Same Gospel Paul Taught?

#STRask

February 16, 2026

Questions about how we can know who is teaching the same gospel Paul taught, and whether or not Jeremiah 1:5 supports the idea that we pre-existed in

What Are Some Good Ways to Start a Conversation About God with Family Members?

#STRask

October 30, 2025

Questions about how to start a conversation about God with non-Christian family members, how to keep from becoming emotional when discussing faith iss

What Is the Role of the Holy Spirit in Our Lives if He Doesn’t Give Us Instructions?

#STRask

February 23, 2026

Questions about the role of the Holy Spirit in our lives, advice for someone who believes in God intellectually but struggles to understand how to hav

Prove to Me That Jesus Is Not a Created Being

#STRask

January 26, 2026

Questions about why we should think Jesus is not a created being, and what it means to say God became fully human if part of being human means not bei

Why Does the Bible Teach You How to Be a Proper Slave Owner?

#STRask

November 13, 2025

Question about why it seems like the Bible teaches you how to be a proper slave owner rather than than saying, “Stop it. Give them freedom.”

* It s

Protestants and Catholics: What’s the Difference? With Chad Van Dixhoorn, Blair Smith, and Mark McDowell

Life and Books and Everything

November 26, 2025

How should Protestants think about the Catholic Mass? About the Eucharist? About the history and development of the papacy? In this panel discussion,

How Can I Explain Modesty to My Daughter?

#STRask

November 27, 2025

Questions about how to explain modesty to a nine-year-old in a way that won’t cause shame about her body, and when and how to tell a child about a pre

Did Jesus Prove He Wasn’t Sinless When He Overturned the Tables?

#STRask

December 29, 2025

Questions about whether Jesus proved he wasn’t sinless when he overturned the tables, whether Jesus’ response to the Pharisees in Mark 3:22–26 was a b

How Would You Convince Someone That Evil Exists?

#STRask

November 17, 2025

Questions about how to convince someone that evil exists, whether Charlie Kirk’s murder was part of God’s plan, whether that would mean the murderer d

The Resurrection Standoff: Licona vs. Ehrman on the Unbelievable Podcast

Risen Jesus

October 22, 2025

This episode is taken from the Unbelievable podcast with Justin Brierly in 2011 when Dr. Bart Ehrman and Dr. Michael Licona address the question: Is t

An Invitation to the 2026 Coram Deo Pastors Conference

Life and Books and Everything

February 18, 2026

"I love being a pastor, and I love pastors, which is why I hope you will consider joining us at the Coram Deo Pastors Conference in 2026." —Kevin DeYo

Why Are So Many Christians Condemning LGB People Just Because of How They Love?

#STRask

January 15, 2026

Questions about Christians condemning LGB people just because of how they love, how God can expect someone to be celibate when others are free to marr

Shouldn’t I Be Praying for My Soul Rather Than for Material Things?

#STRask

February 2, 2026

Questions about whether we should be praying for our souls rather than for material things, why we need to pray about decisions, whether the devil can